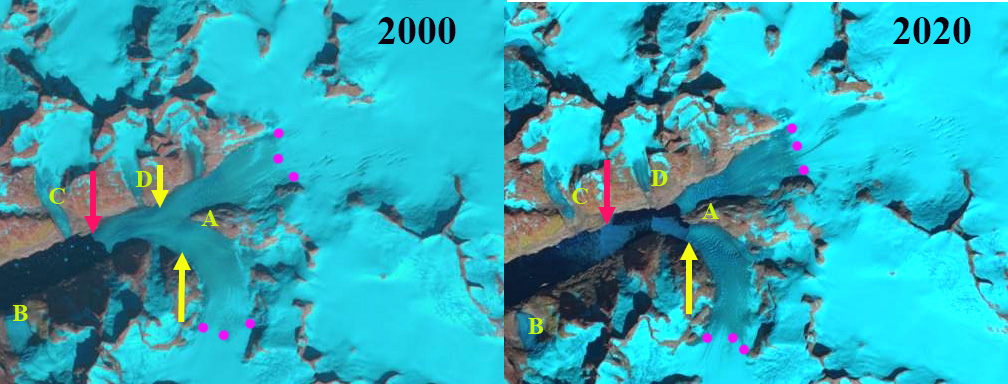

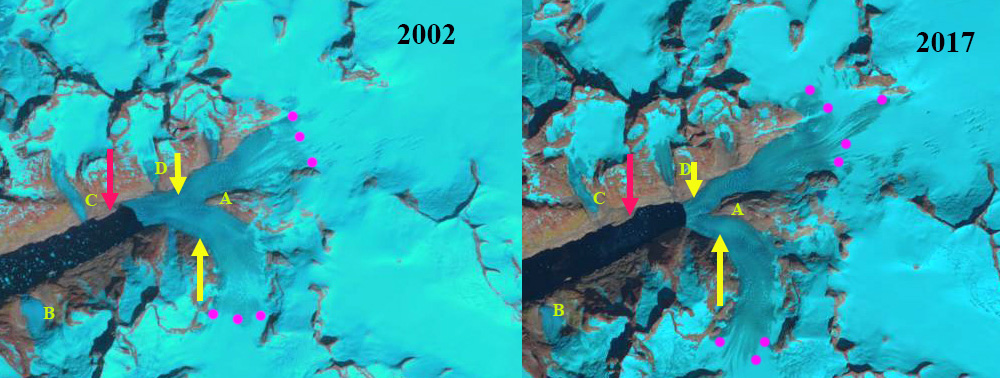

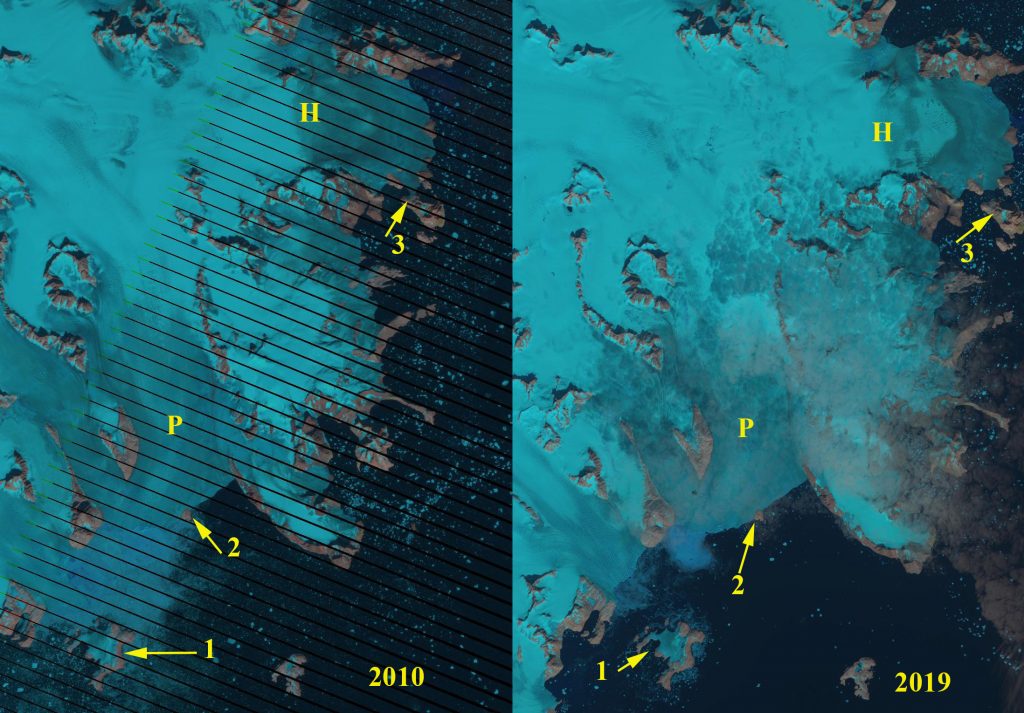

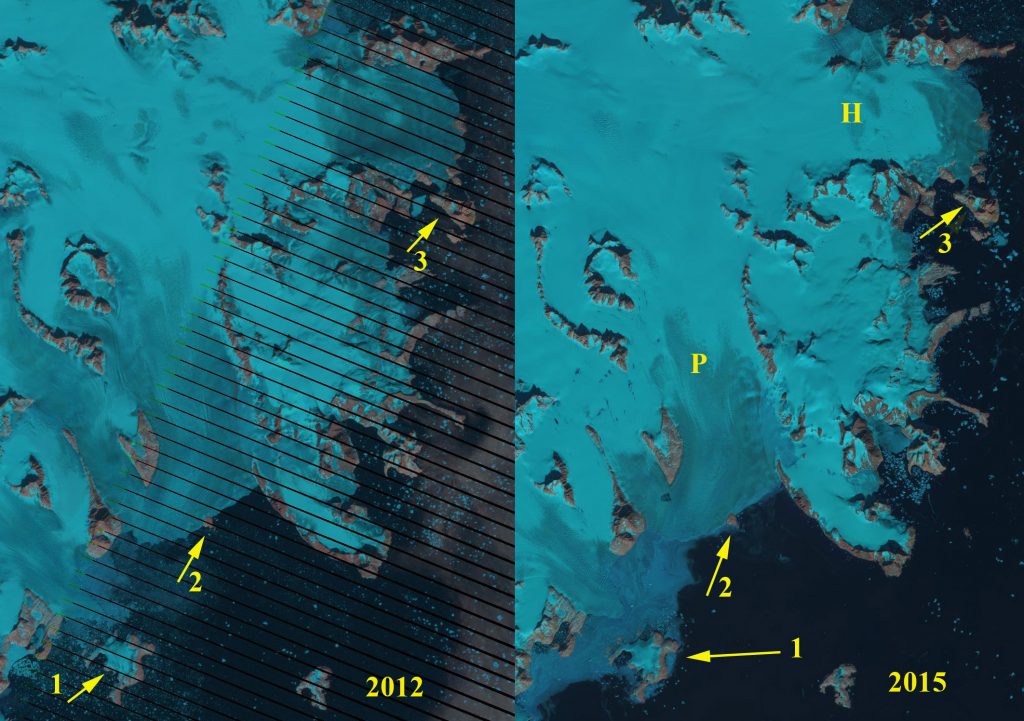

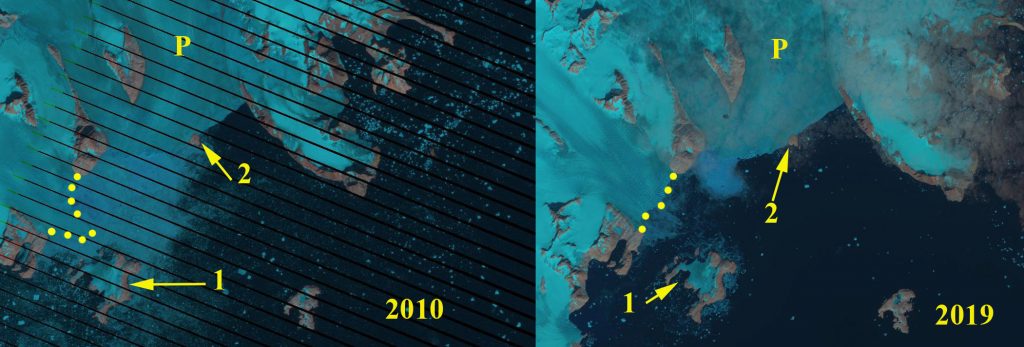

Storstrømmen and L. Bistrup Brae in Landsat imagery from 8-23-2013 and 8-26-2023. Green dots on 2013 image is the 2023 margin. Yellow dots on 2023 image is the 2013 margin. Island A and Island B are at the glacier front in 2013 and are fully separated by 2023. R=Randsoen proglacial lake.

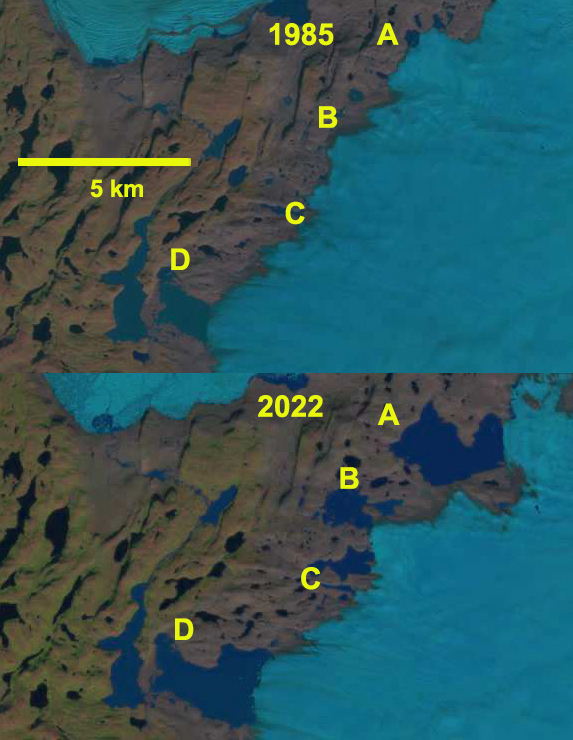

Storstrømmen and L. Bistrup Brae are large outlet glaciers in northeast Greenland that join at their terminus. The calving front is long and has numerous island pinning points. They comprise a large relatively flat low lying terminus region, the southernmost floating ice tongue in East Greenland. Rignot et al (2022) radio echo soundings in August 2020 reveal a seabed at 350–400 m depth the ice shelf front, with shallower terrain (<100 m) over a 30-km wide region to the east that blocks the access of warm, salty, subsurface Atlantic Intermediate Water. This water would accelerate ice shelf bottom melting. They note a ~23 m thinning near the grounding line on Storstrømmen from 1999-2014. They also report a 1.1 km retreat of the grounding line from 2017-2021. Storstrømmen is a surging glacier fed by the NEGIS, that surged 3 times during the 20th century and is in a quiescent phase. The last surge was in 1978-1982. Mouginot et al (2018) indicate the differential between inland thickening and terminus thinning will yield pre-surge conditions by 2027-2030, this transition in elevation change occurs ~50 km inland of terminus. Grinsted et al (2022) point out that the NEGIS has accelerated and expanded laterally, above a point ~200 km inland, between 1985 and 2018, Storstrømmen terminus area is still slowing. Will these inland changes in the NEGIS impact the next surge cycle?

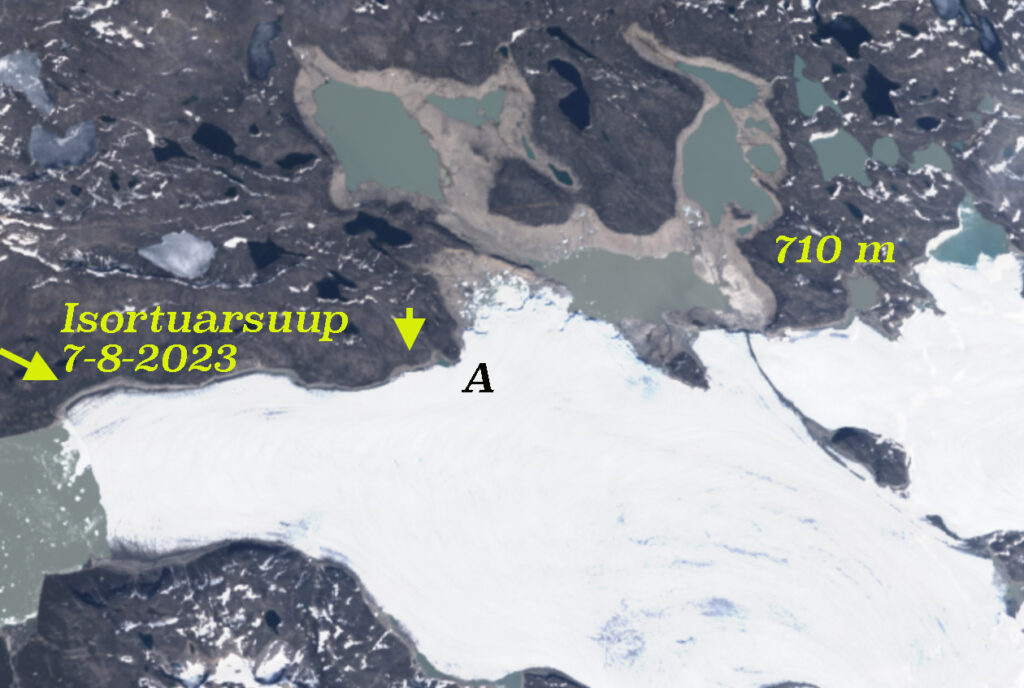

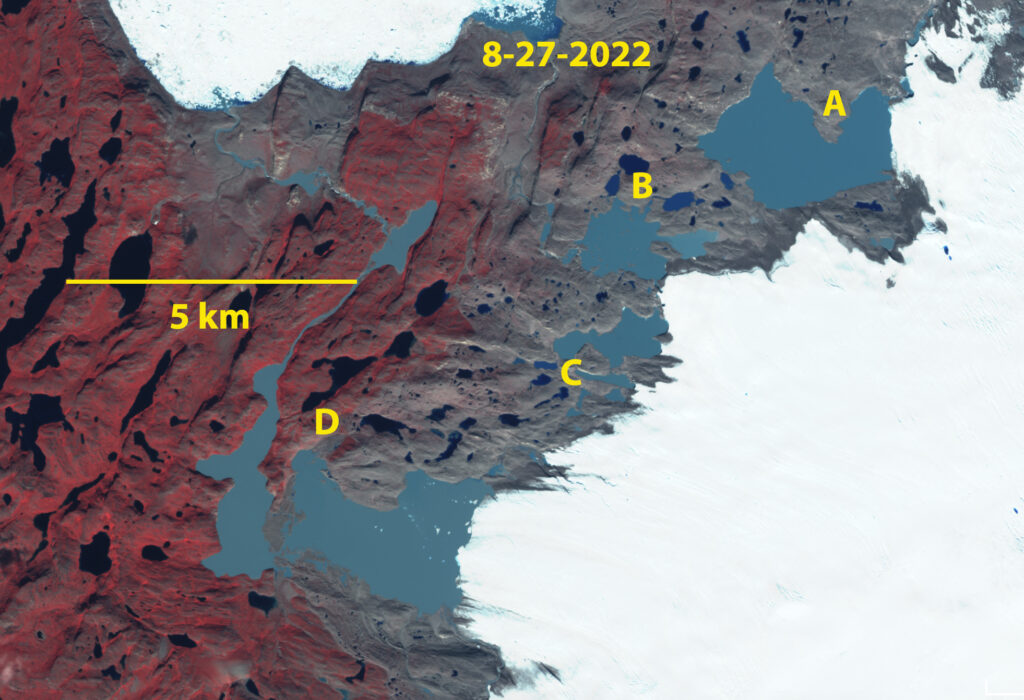

The thinning of the floating ice is leading to retreat and the release of new islands from the glacier. Here we examine Landsat images from 2013 and 2023 to illustrate. Island A is at the front of Storstrømmen in 2023 is 2.1 km from the ice edge. Island B is at the front of L. Bistrup Brae in 2013 and by 2023 is 0.9 km from the ice edge. The other notable change is the expansion of the Randsøen proglacial lake (Point R). The glacier width between Randsøen and the ice front has narrowed from 10 km to 7 km from 2013-2023, with 2.3 km retreat of the main terminus in the embayment. This embayment with a narrow connection between the two glaciers developed in the early 1970’s, but the two glaciers did remain connected (Mouginot et al 2018). There is substantial rifting in this section suggesting the next few years will see significant additional rifting. The supraglacial stream that drains Randsøen, flows along the boundary between Storstrømmen and Bistrup. The flow of this stream parts the sea ice in the Aug. 30, 2023 Sentinel image below. Will the glaciers separate in the next decade and how would that impact the next surge cycle? This post is an update to the 2013 post indicating that Storstrømmen is susceptible to rapid retreat

Storstrømmen and L. Bistrup Brae in Sentinel image from 8-30-2023. Island A and Island B that were at the glacier front in 2013 are fully separated by 2023. R=Randsoen proglacial lake with the yellow arrows indicating surpaglacial stream draining this lake across the glacier and then making a channel through the sea ice and icebergs. Pink arrows indicate rifts that indicate areas prone to calving in next few years.