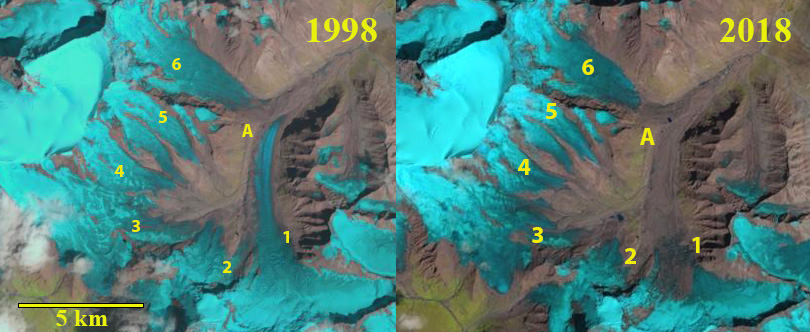

Shafat Glacier in 1997 and 2020 Landsat images. 1-6 are different tributaries with the main glacier being #1. A marks the junction of #1 and #6.

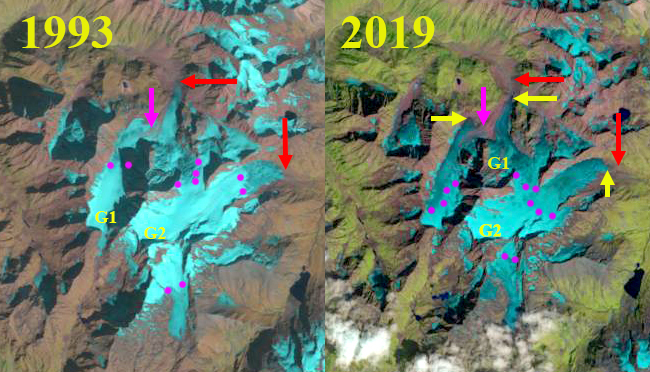

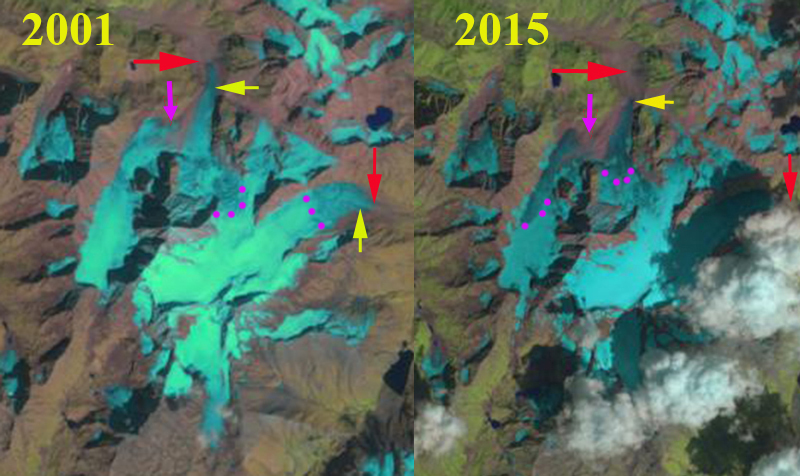

Shafat Glacier occupies the northeast flank of Nun Kun Peak in Ladakh India and drains into the Suru valley. The main valley glacier (1) has been fed by a decreasing number of tributaries. Shukla et al (2020) identified an increase in annual temperature has driven a 6% loss in regional glacier area and a 62% expansion in debris cover from 1971-2017. Here we compare Landsat imagery from 1997-2020 to identify this glaciers response to climate change.

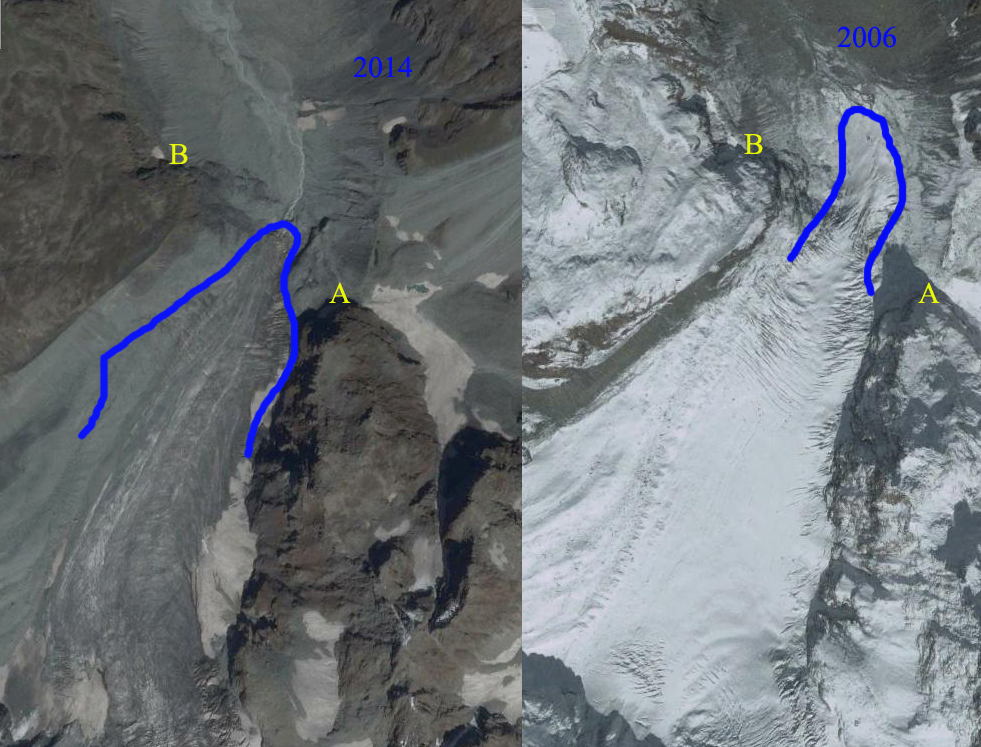

In 1997 and 1998 tributary 2 and 3 join and then the debris covered sections connects to the main valley glacier #1. Tributary 4 terminus is the meeting point of two glacier tongues. The active non-debris covered ice of Tributary #6 reaches to the valley adjacent to Point A where it meets the main valley tongue. The active clean ice of the main tongue extends beyond Point A. In 1997-2000 the terminus is heavily debris covered with the main discharge from beneath the glacier at Point B. The active ice of Tributary 6 extends to within 1.5 km of the terminus, while the active/clean ice of the main tongue extends to within 1.3 km of the terminus. The snowline is at 4900 m in 1997 and 5100 m in 1998. By 2018-2020 the active ice area now ends 2.5 km from the terminus for Tributary 6 and 5.1 km from the terminus for the main glacier. Debris cover extends 5.3 km from the terminus up the main tongue and 2.7 km from terminus at Point B up Tributary 6. Retreat is hard to discern with the extensive stagnant debris covered area. Tributary 4 has separated into two parts, and tributary 2 and 3 have separated from each other and the main valley glacier. In 2018 the snowline is at 5200 m, while in 2020 it is 5050 m. The consistent high snowlines have led to glacier thinning, debris cover expansion, and increasing stagnation of the main glacier tongue. The stagnation is indicated by the increasingly concave cross profile and the lack of crevassing in the lower 5 km of the main glacier tongue below 4600 m. The low slope of the glacier from 4250-4400 m, of 4.8% suggests a proglacial lake could form in this reach of the main valley.

The glacier volume loss is more substantial than the area loss, with retreat less than on Kolahoi Glacier, but volume loss similar (Rashid et al 2019). Loss of glacier area leads to summer glacier runoff declines, which impacts irrigation Rashid et al 2019). The Suru River also has a 44 MW run of river Chutak Hydropower plant.

Shafat Glacier in 1998 and 2018 Landsat images. 1-6 are different tributaries with the main glacier being #1. A marks the junction of #1 and #6.

Digital Globe image of the terminus reach in 2000 and 2019. B marks the location of main river exiting from beneath the glacier. A marks the junction of the two glaciers. 1 and 6 indicate the two main glaciers that join 2 km above the Shafat Glacier terminus. Note debris cover spread particularly on main tongue.