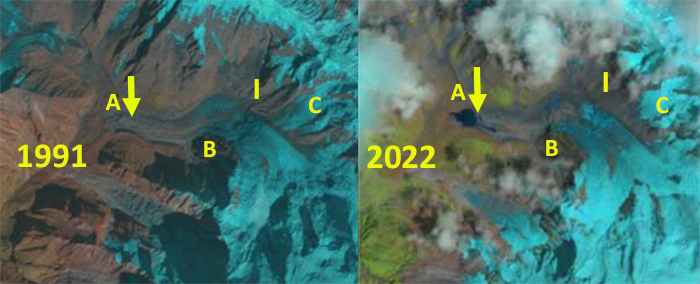

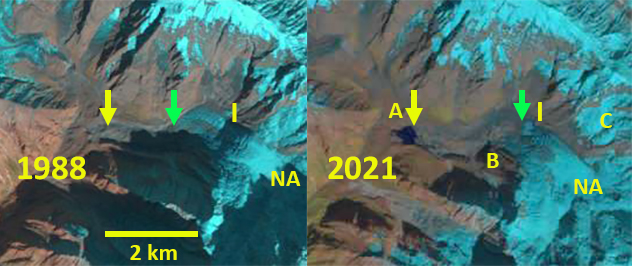

Kanchenjunga Glacier in Nov. 8, 2023 false color Sentinel image. The flowlines of the six tributaries shown in green with the snowline on each at the purple dots. Percentage of glacier length above the snowline for each tributary shown as percentage. Two rapidly expanding supraglacial lakes shown at yellow arrows.

Kanchenjunga Glacier is the main glacier draining west from Kanchenjunga Peak draining into the Ghunsa River. Lamsal et al (2017). report a loss of -0.18 m/year from 1975-2010. They noted an increase in supraglacial ponds and that the glacier had decreased in thickness mainly between the terminus and 5500 m, with some thickness increases above 5850 m. The Kanchenjunga Region has produced 6 to 8 GLOF’s since the late 1960’s, but none from the Kanchenjunga Glacier which had lacked substantial proglacial or supraglacial lakes until now (Byers et al 2020). Here we examine Sentinel imagery indicating the high snowline in November 2020, January 2021 and November 2023.

Kanchenjunga Glacier in Jan,. 17, 2021 false color Sentinel image. The snowline on each at the purple dots. Percentage of glacier length above the snowline for each tributary shown as percentage. Two rapidly expanding supraglacial lakes shown at yellow arrows.

A glacier needs a majority of its area to be in the accumulation zone to maintain its mass balance. In November 2020 the transient snow line averages 5800 m. By January 17, 2021 the snowline has risen to an average of 5950 m. Measuring the distance from the terminus to top of the glacier along the six main tributaries, and determining the percentage of this length above the snowline in the accumulation area, from 8-14% of the length is the accumulation area. This leaves a limited accumulation area. The January 2021 period had an unusually high snowline due to heat wave in January, that led to high snowlines on Mount Everest as well (Pelto et al 2021). In November 2023 the snowline averages 5900 m across the six tributaries, ranging from 10-17% of the length of the tributaries being above the snowline, mcuh too little to maintain equilibrium. The yellow arrows indicate one noteworthy change near the terminus the growth of new supraglacial ponds. The upper pond expanded from 20,000 m² in Nov. 2020 to 80,000 m² in Nov. 2023, the lower pond consisted of three discrete segments with an area of 50,000 m² in Nov. 2020 to 120,000 m² in Nov. 2023. These are the largest supraglacial lakes to appear on this glacier in the last several decades at least. These two ponds have a greater combined area than all ponds on the glacier in 2010 which Lamsal et al (2017) reported as 0.16 km². At that time the largest pond was 30,000 m².

Kanchenjunga Glacier terminus area supraglacial ponds in Nov. 8, 2023 false color Sentinel image. Each has more than doubled in size in last three years, with areas of 80,000 and 120,000 m².

Kanchenjunga Glacier in Nov. 10, 2020 false color Sentinel image. The snowline on each at the purple dots. Two rapidly expanding supraglacial lakes shown at yellow arrows.