Safuna Glacier (S) and Arhuey Glacier (A) in 1992 and 2017 Landsat images indicating glacier retreat from the 1992 terminus red arrow to the 2017 terminus position yellow arrow. Snowline indicated by purple dots.

Safuna Glacier (S) is at the northern end of the Cordillera Blanca Range, Peru flowing north from Nevados Pucajirca. Arhuey Glacier (A) is adjacent to Safuna and flows west formerly terminating in Arhuey Lagunacocha impounded by a moraine. Safuna Glacier in 1992 terminated in Laguna Safuna Alta, which is impounded by a moraine dam and has a history of water level fluctuations. Reynolds Geosciences (2003) provides a detailed look at the lake, moraine and associated engineering. The moraine appeared unstable in the 1960’s prompting excavation of a tunnel through the moraine in 1970, which ended up below the lake water level after the lake surface elevation dropped 25 m in late 1970. In 1978 a second tunnel was constructed, that to date remains above the lake waterline and has not been used. The Peruvian Government was early in their proactive engineering to address glacier lake outburst flood hazards (Carey, 2008). In 2002, a rockslide created a wave of at least 80 meters in height (Reynolds Geosciences , 2003), overtopping the moraine and damaging both tunnels but not damaging the moraine. This landslide also filled in the lake reducing depth significantly. Here we examine changes from 1992 to 2017 using Landsat imagery from July of Safuna Glacier (S) and Arhuey Glacier (A). Though glacier outburst floods have capture more attention it is the overall reduction in glacier water runoff that has more impact on local communities (GlacierHub-Angle, 2017).

In 1992 the glacier terminated in the 800 m long Laguna Safuan Alta, red arrow . The lower glacier featured a long narrow valley tongue extending into the lake. By 1995 retreat had led to further lake expansion, with the glacier still reaching the lake across a narrower front. In 1996 as was the case in 1992 and 1995 the snowline on the glacier is above the main icefall area where the valley tongue descends from the accumulation zone, purple dots at an elevation of 4950 m. By 2015 the glacier had receded from the shore of the lake and the terminus is covered in debris from the 2002 landslide. In 2015 and 2016 the snowline is higher than in the 1990 at 5100 m. In 2017 the glacier terminates 200 m from the lake shore and 500 m from the 1992 terminus location. The lake is now 1100 m long. The glacier no longer can easily release ice avalanches into the lake

The retreat of this glacier mirrors that of Arhuey Glacier (A), which terminated in the newly forming Arhuey Lagunacocha. By 1995 and 1996 the terminus tongue is more distinct and the lake is 400-500 m long. By 2015 and 2016 the glacier has retreated to the far end of the lake basin, though still in contact with the lake By 2017 the lake is 1150 m long, indicating a 700 m retreat since 1992. The upper portion of the glacier remains incredibly crevassed indicate vigorous accumulation and motion. The glacier has a relatively small ablation zone with the loss of the flatter terminus reach, and should have a reduced rate of retreat. The glacier now has a reduced but still significant ability to release ice avalanches into the lake. The glacier fits into the Cordillera Blanca regional pattern which has experienced a 22% glacier loss from 1970-2003 (Racoviteanu et al, 2008).

Emmer et al (2016) note that the number of GLOF’s were greater from moraine dammed lakes in the region early in the retreat phase in the 1940’s and 1050’s. This suggest the moraines are becoming more stable with time since formation and glacier retreat. The broader impact of climate change is examined by the GlacierHub (Marconi, 2016).

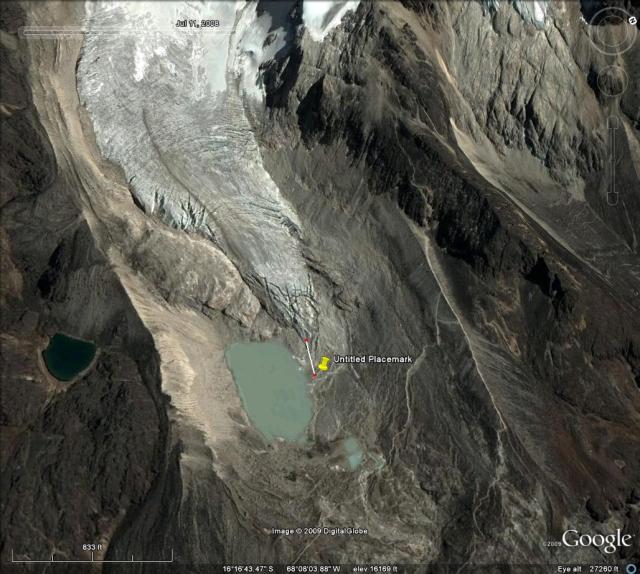

Safuna Glacier, Laguna Safuna Alta and Laguna Safuna Baja (SB), blue arrow recent 2002 landslide scar and yellow arrow 2017 terminus.

Arhuey Glacier and Arhuey Lagunacocha. Black arrows indicate heavy crevassing, blue arrow recent landslide scars and yellow arrow 2017 terminus.

Safuna Glacier (S) and Arhuey Glacier in 1995 and 2015 Landsat images indicating glacier retreat from the 1992 terminus red arrow to the 2017 terminus position yellow arrow. Snowline indicated by purple dots.

Safuna Glacier (S) and Arhuey Glacier in 1996 and 2016 Landsat images indicating glacier retreat from the 1992 terminus red arrow to the 2017 terminus position yellow arrow. Snowline indicated by purple dots.