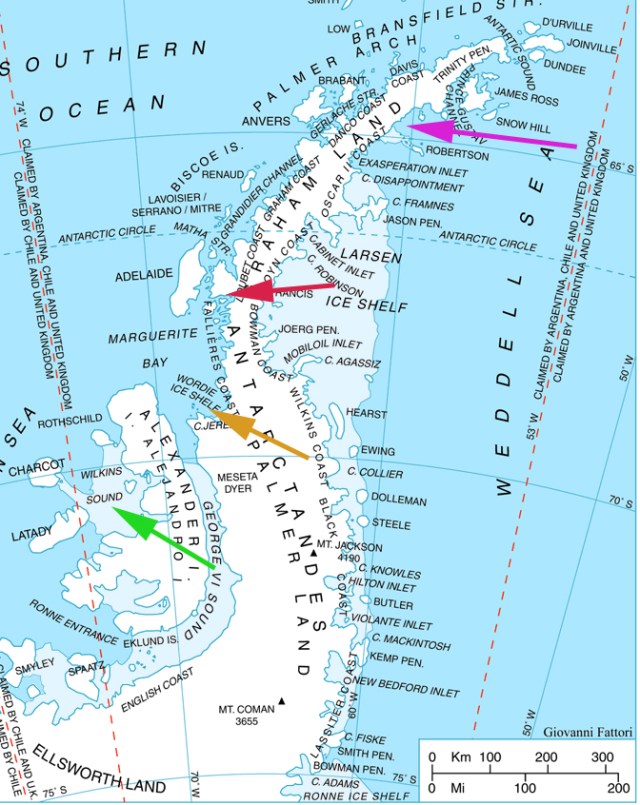

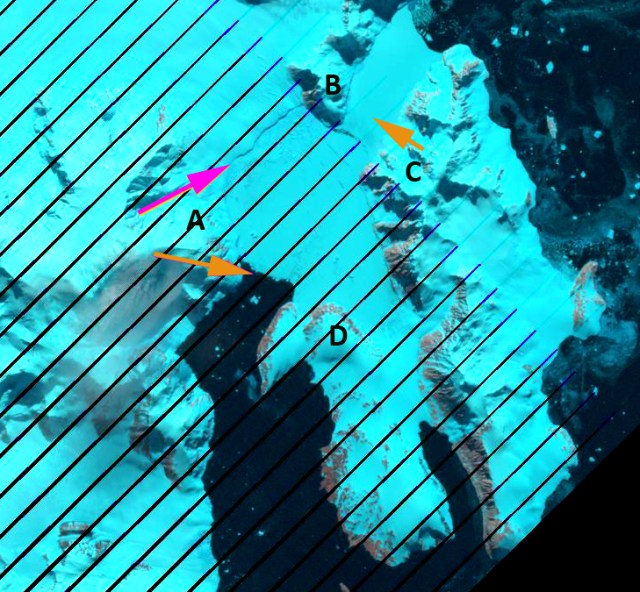

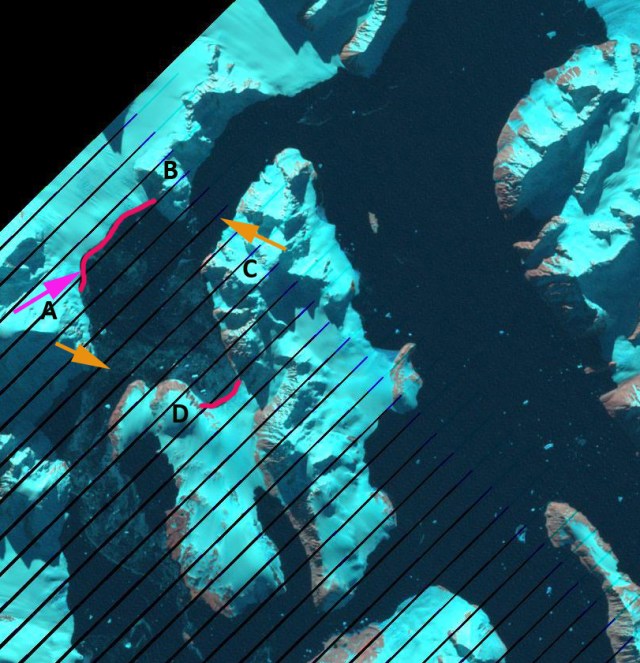

Eagle Island Ice Cap, Antarctica in Landsat images from Feb. 4, 2020 and Feb. 13, 2020. Point E indicates an are area of snow/firn that is saturated with meltwater. Point A and B indicate locations where the amount of bare rock/ground and hence albedo have changed dramatically.

This post was source for an article by Kasha Patel published by NASA Earth Observatory, CNN and Washington Post.

Update in December 2022 snowcover is less extensive than observed in 2020 or 2021.

The impact of period of record warm weather over the Antarctic Peninsula has been the rapid development of melt features on some of the glaciers near the tip of the Peninsula, where the temperature records were set at Esperenza and Marambio Base. Here we examine Landsat imagery of the Eagle Island Ice Cap (63.65 S 55.50W), 40 km from Esperanza, from January 12-February 13, 2020 to identify surface melt extent and surface melt feature development. Xavier Fettweis, University of Liege Belgium, using the MAR climate model output forced by the Global Forecast System (GFS) to generate daily melt maps for Antarctica, for Esperanza the melt map for recent weeks, shown below indicates that daily melt increased to above 30 mm/day, with a maximum temperature on the warmest day of 18.3 C (65 F). This compares to melt rates seen on the warmest days on temperate glaciers, such as the North Cascade Range, Washington of 80 mm/day and averaging 24 mm/day for the warmest months (Pelto, 2018). This short term weather event fits into the pattern of overall regional warming that has led to a rapid glaciological response, with 87% of glaciers around the Antarctic Peninsula receding Davies et al (2012). The event regionally was examined by Robinson et al (2020),who noted implications for flora.

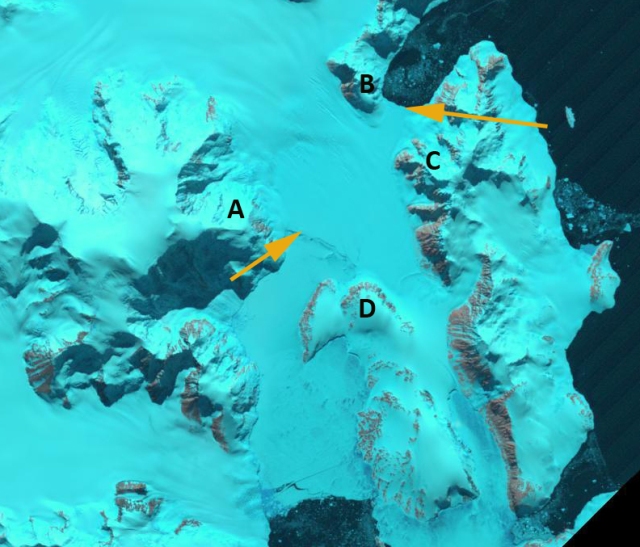

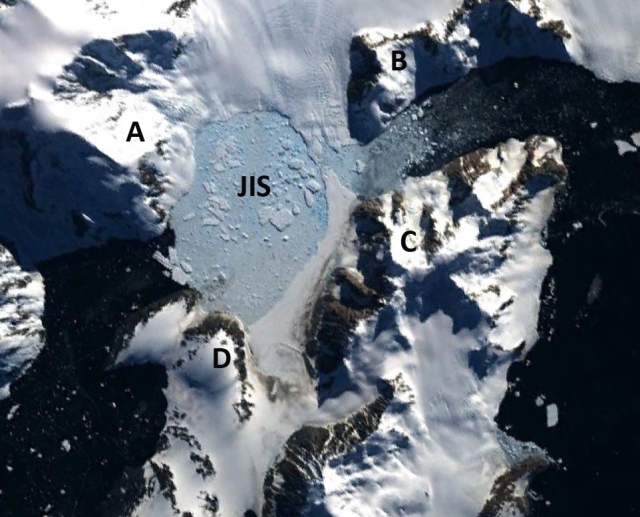

On January 12, 2020 Landsat imagery indicates a substantial area of bare ice/firn (gray-blue) on the western outlet glacier near Point A. The brighter electric blue color indicates accumulated snow from the most recent winter season, this covers 60% of the ice cap. The Jan. 27 image shows little change in the snowcover extent or the extent of older firn and ice exposed by melt. The Feb. 4, 2020 image indicates a new snowfall has covered the ice cap. The precipitation graph provided by Xavier Fettweis indicates two snow events between Jan. 28 and Feb. 4 of approximately 5 mm water equivalent each. The warm temperatures began on Feb 5 and continued up to the date of the Landsat image on Feb. 13. At Point E is a ~1.5 km2 area of cobalt blue that indicates snow/firn pack that is saturated with meltwater that has quickly developed. There is an additional ring of saturated snow/firn northeast of Point E. The snow swamp that has developed is due to the combination of melt, a total of 106 mm by Xavier’s model from Feb.6-Feb.11 and a rain event that occurred on Feb. 12 of ~6 mm. Peak melt reached 30 mm on Feb.6 similar to that at Esperanza. Point E is at the summit of the icecap between 250 and 300 m elevation. The area of bare ice (blue-gray) has expanded at Point A and Point B. This higher albedo will enhance ablation in the near future before new snowfall covers the ice cap again. The bedrock area near Point B has also expanded merging a couple of isolated bedrock knobs.

The impact of short term melt events like this on an ice cap like this, is visible and significant for annual mass balance, but not large in terms of long term glacier mass balance (volume change) and area. The accumulation rate on nearby James Ross Island is ~600 mm/year. Hence, this one melt event represents the loss of ~20% of the seasonal accumulation (Abram et al. 2011). In Antarctica specific anomalously warm days are when most mass balance losses occur. Barrand et al (2013) note a strong positive and significant trend in melt conditions in the region.The increasing frequency and cumulative impact of events like this is significant to mass balance. Mass balance regionally has been negative driving retreat and ice shelf disintegration as noted at nearby Mondor Glacier, Muller Ice Shelf and Eyrie Bay.

Eagle Island Ice Cap, Antarctica in Landsat images from Jan. 12, 2020 and Jan. 27, 2020. Point E indicates the top of the ice cap and it is an area of snowcover. Point A is adjacent to outlet glacier that has bare ice exposed. Point B is above a fringing area of bare firn and ice at the southern margin of the ice cap and island.

Meltwater production time series at Esperanza Base from MAR-GFS From Xavier Fettweis.

Meltwater production time series at Eagle Island from MAR-GFS From Xavier Fettweis.

Precipitation time series at Eagle Island from MAR-GFS From Xavier Fettweis.

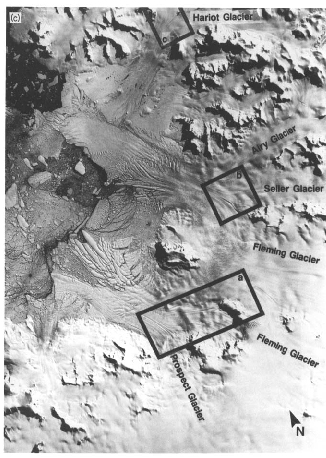

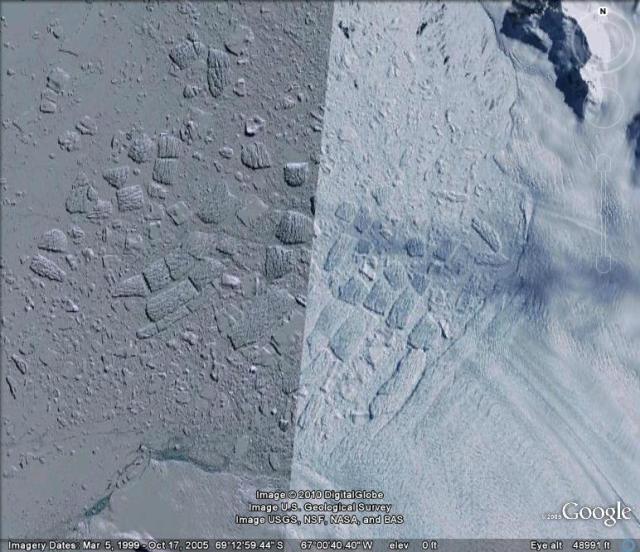

Eagle Island in Antarctica REMA viewer from Feb. 2017 indicating the snocovered ice cap with some melt area near the outlet glacier to the northwest and on the southern margin. the right hand image is the DEM of the area contoured in 25 m intervals With summit area of the ice cap above 250 m.