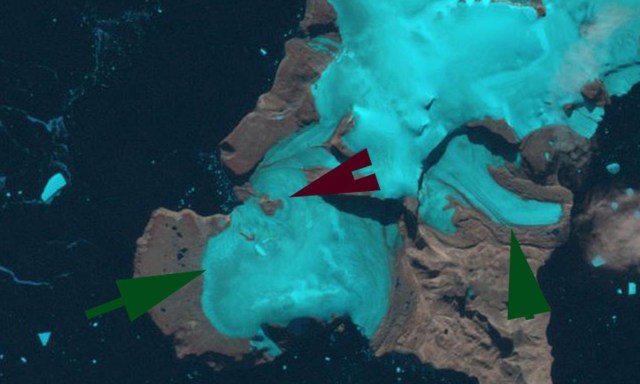

Figure 1: Study sites considered in this article: Seller Glacier and Heim Glacier (Landsat-8 image courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey)

Post by Mariama Dryak

Iceberg melt is caused by the temperature of the water in which an iceberg floats and the velocity of the water flowing around the iceberg. As a result, iceberg melt is an excellent indicator for the ocean conditions in which an iceberg resides. Given the remote location of Antarctica, and the difficulty in taking direct oceanographic measurements immediately in front of glacier termini in Antarctica, icebergs near glacier fronts can act as a useful proxy for what the ocean conditions are in these areas, especially under changing climate.

Dryak and Enderlin (2020) compared remotely-sensed iceberg melt rates (2013 – 2019) from eight study sites along the Antarctic Peninsula (AP) to glacier frontal ablation rates (2014 – 2018) where they overlapped in time and found a significant positively correlated relationship between the two. In general, iceberg melt rates were found to be much lower on the eastern AP where ocean waters are characterized as very cool relative to the heterogeneous, but generally warmer, waters on the western AP–where iceberg melt rates were higher. When we take a closer look at the data and consider what this means in the context of a stratified water column, the iceberg melt rate magnitudes also make sense relative to one another and what is known of regional ocean conditions.

Here we take a look at the results from two of those study sites: Seller Glacier and Heim Glacier.

Seller Glacier is the southernmost study site considered in our study on the Antarctic Peninsula, and produces very large, sometimes tabular icebergs with relatively high mean melt rates. Figure 2 indicates the changes in the same iceberg at two points in time. These icebergs are larger than and different in style to all of the other study sites, with the Seller Glacier terminus also being the widest of all the glaciers considered in the study. Due to the large area of the icebergs produced, we know that the keel depths of these icebergs also extend deep into the water column (See Table 1, Dryak and Enderlin, 2020), contacting warm subsurface waters (and some contacting Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW)) as characterized by Moffat and Meredith (2018) in Figure 3 below. In the upper layers these icebergs also sit in the very cold Winter Water (WW) layer and expanded section of Antarctic Surface Water (AASW) prevalent in the Seller region.

Figure 2: An iceberg from Seller Glacier in 2014 and later in 2016. Mean submarine melt rates for the Seller Glacier icebergs from this time period were 6.54 cm/day (Imagery © [2019] DigitalGlobe, Inc.)

Figure 3: Figure 3 from Moffat and Meredith (2018).

Frontal ablation rates at Seller Glacier are higher than expected given iceberg melt rates at the other sites on the western Antarctic Peninsula (Figure 4). Dryak and Enderlin (2020) suggest this to be because of a long-term dynamic adjustment of the Seller Glacier in response to the collapse of the Wordie Ice Shelf, which occurred between 1966 and 1989 (Vaughan, 1991)-a similar case to the sustained elevated velocities witnessed at Crane Glacier on the eastern Antarctic Peninsula following the collapse of the Larsen B Ice Shelf in 2002.

Figure 4: Scatterplot of iceberg melt rates and frontal ablation for nearby glaciers over near-coindicdent time periods. Symbols indicate median frontal ablation rates. Figure 8 from Dryak and Enderlin (2020)

In contrast, the study site at Heim Glacier, north of Seller Glacier, contains smaller, shallow icebergs with low iceberg melt rates on par with iceberg melt rates found on the eastern Antarctic Peninsula. The glacier that produced the sampled icebergs, though not the smallest of the sites sampled, produces icebergs small in area that often do not last from one season to the next. The keel depths of the sampled icebergs at Heim Glacier likely do not reach below the cold WW layer (Table 1, Dryak and Enderlin, 2020), terminating in the very cold water layer or above in the compressed and comparatively cool AASW. However, the Heim study site is also located near the Marguerite Trough, an area of deep bathymetry known for the presence of warm waters, so the low melt rates here may be surprising to some without taking a closer look at the specific locale. Our study suggests that the bathymetry of the area in which the icebergs reside might be sheltered due to the presence of Blaiklock and Pourquoi Pas Islands, which may deflect warmer waters from reaching the Heim Glacier.

Frontal ablation rates at Heim Glacier are low, and of a similar magnitude to eastern Antarctic Peninsula sites, corresponding in magnitude to the low iceberg melt rates for the site as well (Dryak and Enderlin, 2020; Figure 8).

Overall, this paper re-emphasizes the importance of considering the ocean’s role in forcing changes on glaciers that terminate in the ocean around Antarctica, especially under changing climate. With the ocean acting as a large sink for excess heat in the atmosphere, evaluating the consequences of the storage of this heat in the ocean is essential when attempting to understand the feedback mechanisms associated with such change. The moral of the story is that we must keep one eye on the ocean going forward and how it could lead to changes in glacier dynamics, which could lead to changes in the contributions of glaciers to sea level and the marine ecosystems that exist within the ocean.

For full results and discussion of all of the study sites considered along the western and eastern sides of the Antarctic Peninsula, read the full Dryak and Enderlin (2020) article in the Journal of Glaciology.

*Note the Seller Glacier like many others in the region have experience rapid retreat in the last 30 years, Fleming Glacier, Sjogren Glacier and Boydell Glacier.