Ladevali (L), Tsaigmili (T), Baki (B), and Cherinda Glacier (C) in Sentinel false color image from August 30, 2022. Illustrating that each has 10% or less of the glacier surface retaining snowcover.

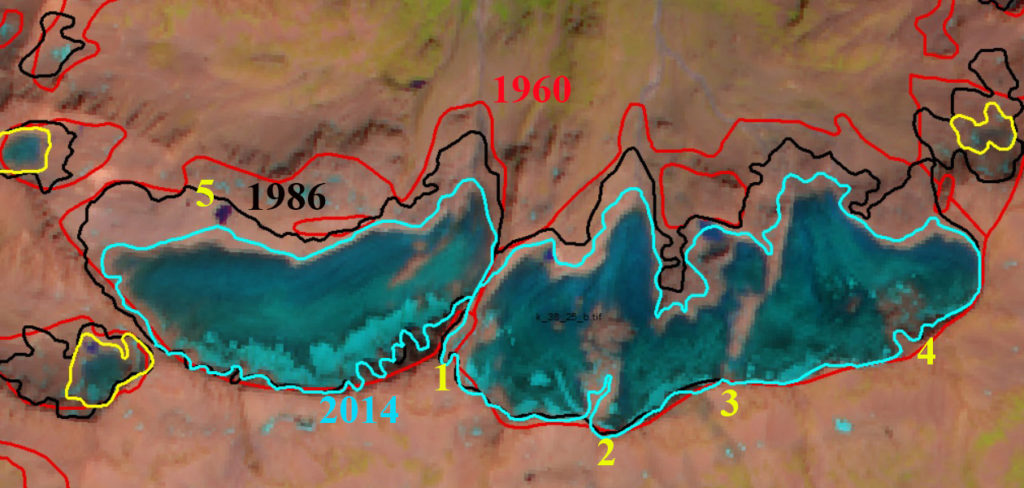

Several glaciers at the headwaters of the Doira River in the Zemo Svaneti Planned National Park in the Georgian Caucasus have been stripped of snowpack during recent summers. A glacier without a zone a persistent snowcover throughout the year has no accumulation zone and cannot survive (Pelto, 2010). Here we examine Ladevali, Tsaigmili, Baki and Cherinda Glaciers during August of 2016, 2018, 2020 and 2022 using Sentinel imagery. Tielidze and Wheate (2018) completed an inventory of Caucasus glaciers documenting the 1986 glacier surface area at 1482 square kilometers decreasing to 1193 square kilometers by 2014, a 20% decline in this 28 year period. Tielidze et al ( 2022) update this inventory identifying a 23% decline in area from 2000 to 2020, greater than 1% per year.

In 1998 ther Ladvali and Tsaigmili Glacier nearly join at the terminus. Baki Glacier spans the entire upper basin and no lake is evident near Point B. Cherinda Glacier descends a bedrock step to form a lower section. In mid-August of 2018 Baki Glacier has lost nearly all snowcover and a new lake has formed adjancent to Point B. Cherlinda Glacier has a fringe 15% along its upper margin and is no longer connected to lower relict ice below the bedrock step. Ladevali and Tsaigmili Glacier have snow cover above 3200 m covering 15-20% of the glacier and the termini are now separated by ~1 km. At the end of August in 2020 Baki Glacier is snow free. Cherinda has a fringe on its upper maring covering less than 10% of the glacier. Ladevali and Tsaigmili Glacier have snow cover above 3300 m covering ~5% of the glacier. At the end of August 2022 Baki Glacier is again snow free, while Cherinda has a fringe on its upper margin covering 10% of the Glacier. Ladevali and Tsaigmili Glacier have snow cover above 3250 m covering ~10% of the glacier. In 2022 the glaciers also exhibit a lack of retained firn from any recent year, illustrating a consistent lack of retained accumulation. This consistent minimal retained snowcover illustrates that the glaciers cannot survive current climate. A similar situation has been observed further east at Gora Gvandra. The mass balance in the region has continued to decline with a mean annual loss of ~-0.5 m/year from 2000-2019, (Tielidze et al 2022) with 2020-2022 likely even worse

Ladevali (L), Tsaigmili (T), Baki (B), and Cherinda Glacier (C) in Sentinel true color image from August 30, 2020. Illustrating that each has 10% or less of the glacier surface retaining snowcover.

Ladevali (L), Tsaigmili (T), Baki (B), and Cherinda Glacier (C) in Sentinel false color image from August 16, 2018. Illustrating that each has 20% or less of the glacier surface retaining snowcover with several weeks left in the melt season.

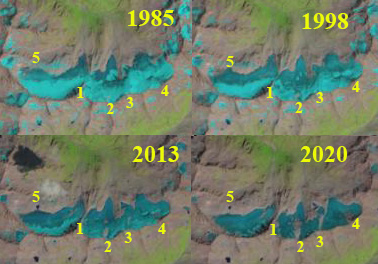

Ladevali (L), Tsaigmili (T), Baki (B), and Cherinda Glacier (C) in Landsat image from mid-August 1998. Ladvali and Tsaigmili nearly join in 1998. Baki Glacier expands across the entire basin and Cherlinda descends below a bedrock step.