Landsat images from 1990 and 2020 of the Mueller (M), Hooker (H), Tasman (T) and Murchison (Mn) Glacier. Red arrows indicate the 1990 terminus location, yellow arrows the 2020 terminus location and pink arrows the upglacier extent of debris cover in 1990.

Glaciers of the Southern Alps of New Zealand have been losing ice volume since 1978, with an increasing rate in the last decade (Pelto, 2016). Gjermundsen et al (2011) examined glacier area change in the central Southern Alps and found a 17% reduction in area mainly from large valley glaciers such as Hooker, Mueller, Tasman and Murchison Glacier. The NIWA glacier monitoring program noted that 30 per cent of New Zealand’s ice that was existed in the late 1970s has been lost in the past 40 years as snowlines have been rising. The retreat has been driven by a series of increasingly warm summers (NIWA, 2019). The NIWA and University of Wellington 2020 snowline survey indicated improvement in 2020. Lauren Vargo and Andrew Lorrey reported there was more retained snowcover compared to the very high snowlines in 2018 and 2019, despite the presence of ash/dust from Australian fires (NIWA, 2020).

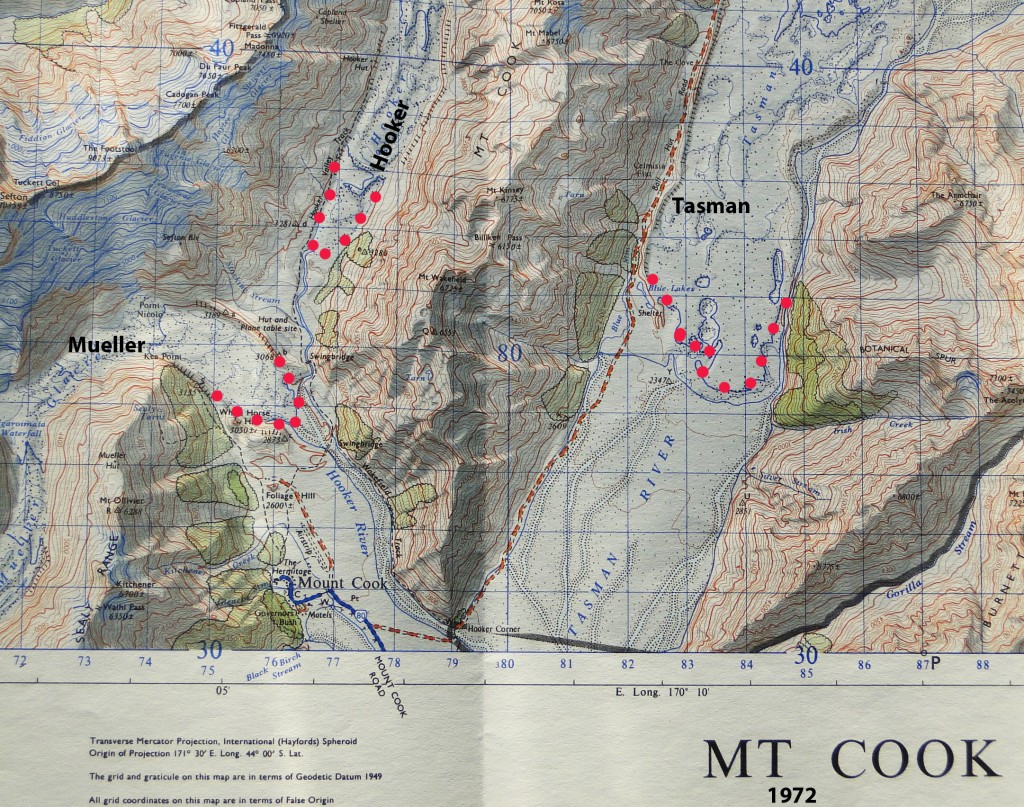

If we look back to the 1972 Mount Cook map, see below, no lakes are evident at the terminus of Hooker (H), Mueller (M), Tasman Glacier (T), or Murchison Glacier that all drain into Lake Pukaki, pink dots indicate terminus location. In 1990 four lakes had developed one in front of each retreating glacier with a combined area of 2.5 km2. By 2020 the combined lake area is 12.9 km2.

Mueller Glacier has had a 2300 m retreat from 1990-2020, which will continue in the future as the lower 1.2 km section of the glacier is stagnant. Mueller Lake area was under 0.2 km2 in 1990, expanding to 1.9 km2 by 2020. Mueller Glacier’s lower section is not a typical convex valley glacier, but a concave reach of debris covered ice with significant melt valleys and hollows indicating stagnation in the lowest 1.6 km. In 1990 a fringing discontinuous area of water along the southern glacier margin existed. By 2004 the Mueller Glacier Lake had expanded to a length of 700 meters. Mueller Lake in 2010 had a surface area of 0.87 km2 and a maximum depth of 83 m (Robertson et al, 2012). By 2015 the lake had reached 1800 meters in length. From 2015-2020 the terminus collapsed into the lake with icebergs and other attached ice remnants. Terminus images from 2018, taken by Jill Pelto, indicate the high turbidity of the lake, which is expected from a debris covered ablation zone.

Hooker Glacier retreated 1350 m from 1990 to 2020 with the retreat enhanced by calving in Hooker Lake. The lake had an area of 0.5 km2 in 1990, expanding to 1.5 km2 by 2020. The retreat was faster during the earlier part of this period with lake area reaching 1.22 km2 by 2011 (Robertson et al.,2013). Hooker Glacier has a low gradient which helps reduce its overall velocity and a debris covered ablation zone reducing ablation, both factors increasing response time to climate change (Quincey and Glasser 2009). Hooker Lake which the glacier ends in began to form around 1982 (Kirkbride, 1993). The peak lake depth is over 130 m, with the terminus moving into shallow water after 2006 leading to declining retreat rates (Robertson et al, 2012). The debris cover now extends ~2 km further upglacier than in 1990.

Tasman Glacier retreated 4900 m from 1990 to 2020 primarily through calving into the expanding proglacial lake. In 1990 Tasman Lake had an area of 1.7 km2, expanding to 7.1 km2 by 2020. Dykes et al (2011) note a maximum depth of 240 m, and an annual growth rate of 0.34 km2 . The proglacial lake at the terminus continues to expand as the glacier retreats upvalley. The lake is deep with most of the lake exceeding 100 metes in depth, and the valley has little gradient, thus the retreat will continue. It has been noted by researchers at Massey University that the lake can expand in this low elevation valley another 9 km, and that at the current rate this could occur over two decades. The debris cover now extends ~1.5 km further upglacier than in 1990.

Murchison Glacier has retreated 2700 m From 1990 to 2020. In 1990 the lake had an area of under 0.2 km2, expanding to 2.5 km2 by 2020. The rapid retreat will continue as 2010, 2013 and 2015 imagery indicate other proglacial lakes have now developed 3.5 km above the actual terminus. The debris cover now extends ~2 km further upglacier than in 1990.

For each glacier debris cover now extends further upglacier which along with rising snowlines highlights the expansion of the ablation area, that also drives volume loss, retreat and lake expansion.

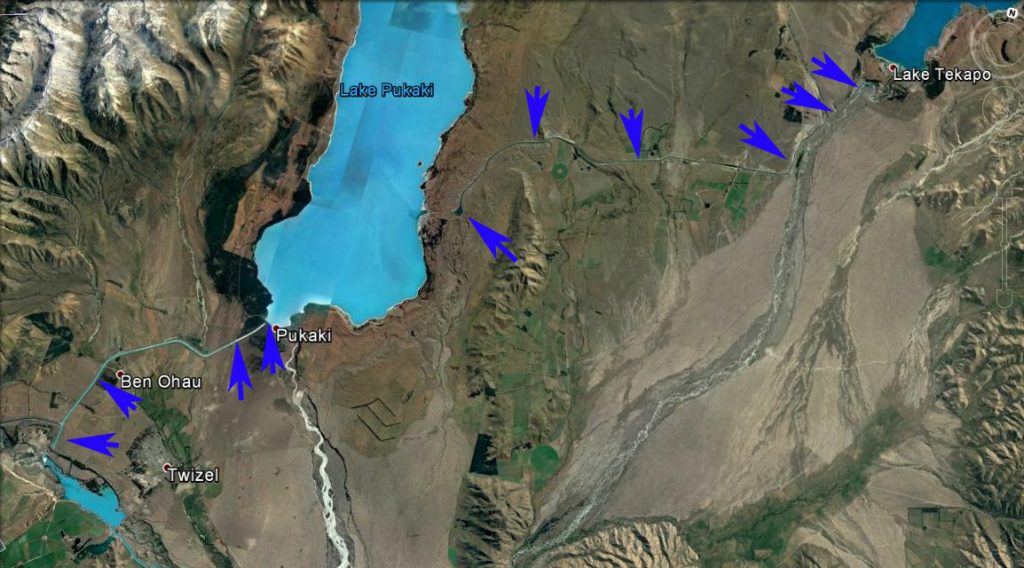

Glacier runoff is a key hydropower water resource. Water from Lake Pukaki is sent through a canal into the Lake Ohau watershed and then through six hydropower plants of the Waitaki hydro scheme: Ohau A, B and C. Benmore, Aviemore and Waitaki with a combined output of 1340 MW. Meridian owns and operates all six hydro stations located from Lake Pūkaki to Waitaki. Interestingly salmon have been introduced into the Waitaki River system for fishing near its mouth, though Lake Pukaki itself has limited fish.

Mueller Glacier terminus collapse in 2018, image from Jill Pelto.

1972 Map of region when Tasman, Mueller and Hooker Glacier lacked proglacial lakes.

Canals draining from Lake Tekapo to Lake Pukaki then upriver of Lake Benmore