Ice Worm Glacier is an east-facing cirque glacier on the east flank of Mount Daniel, WA. Mount Daniel is on the crest of the North Cascade Range of Washington, the crest separates the dry east side that drains to the Columbia River and the wet west side that drains to Puget Sound. The glacier is at the headwaters of Hyas Creek, which drains into the Cle Elum River and the Cle Elum Reservoir. The Cle Elum Reservoir has a storage volume of 538,900,000 m3 and is primarily used for flood control in spring, and agricultural irrigation in summer. This reservoir is the largest in the Yakima River Basin and provides irrigation to 180,000 hectares of agricultural land. The glacier is located in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness area which prohibits the use of mechanized equipment. The Ice Worm Glacier cirque floor is at 1940 m and the headwall at 2050 m. There is a bench at 2150–2300 m that held a glacier/perennial icefield prior to 2015. The glacier is accessed by backpacking 8 km from the Cathedral Rock trailhead with the same base camp used each year at 1700 m on the bank of Hyas Creek. Detailed publication by Mauri and Jill Pelto at: Loss of Ice Worm Glacier, North Cascade Range, WA USA, 2025.

The glacier is fed by wind drift accumulation along the ridge that was just above the top of the glacier during the 1944-2000 period. Avalanching from the slopes below the East Peak of Mount Daniel and from the ridges extending along the north and south flank of the glacier have also been significant. The glacier is part of the Mount Daniel-Mount Hinman Glacier Complex just south of Highway 2 and sits astride the Cascade Divide. This complexcomprised of 9 glaciers covering 3.8 km2 in 1984. This was the biggest cocentration of glaciers between Mount Rainer and Glacier Peak. At the end of the summer 2023 melt season only three of these remain as glaciers, Daniels, Foss and Lynch Glacier. We began monitoring these glaciers along with Ice Worm Glacier in 1984.

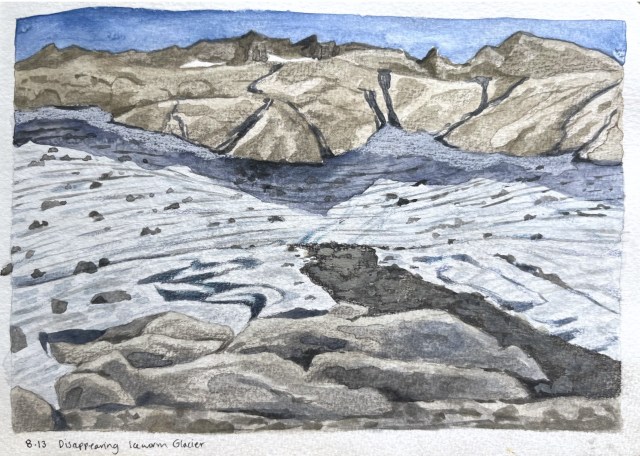

Ice Worm Glacier Evolution

In 1986 William (Bill) Prater, who had made many first ascents in the area between 1944 and 1960, joined us in the field. Bill also had invented and patented (1973) the first snowshoe with a claw attached to its binding, the Sherpa Snowshoe. Comparing images from these early visits with the current margin of Ice Worm Glacier indicated that there had little change in this glacier from 1944-1986. The mapped area in 1958 was 0.19 km2 (GLIMS, 2023), in 1986 we mapped the area at 0.18 km2.

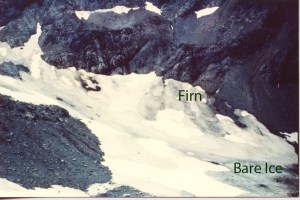

Each summer during the third week in August we measure the mass balance of this glacier. Because the glacier lacks crevasses we simply grid the glaciers with measurements made 50 m apart along transects running up the glacier and across the glacier along the margins. We also completed a longitudinal profile running up the glacier from a fixed location on the bedrock at the below and at the top of the glacier. The surface elevation was determined at the specific 50 m points to identify thinning of the glacier. During the first decade the glacier extended to within 10 m of the ridge on the south side of the glacier, allowing us to ski off of the ridge, see 1990 image below.

Glacier Area Change

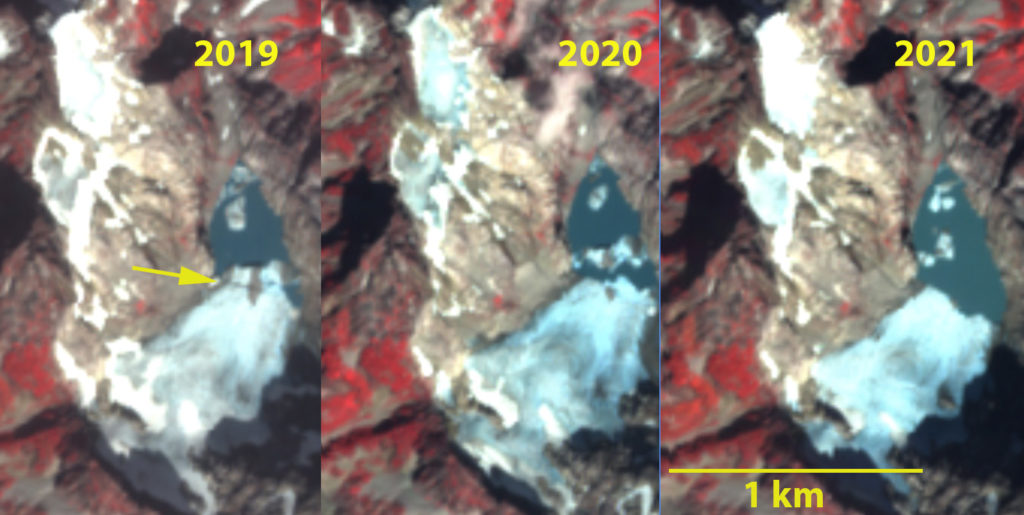

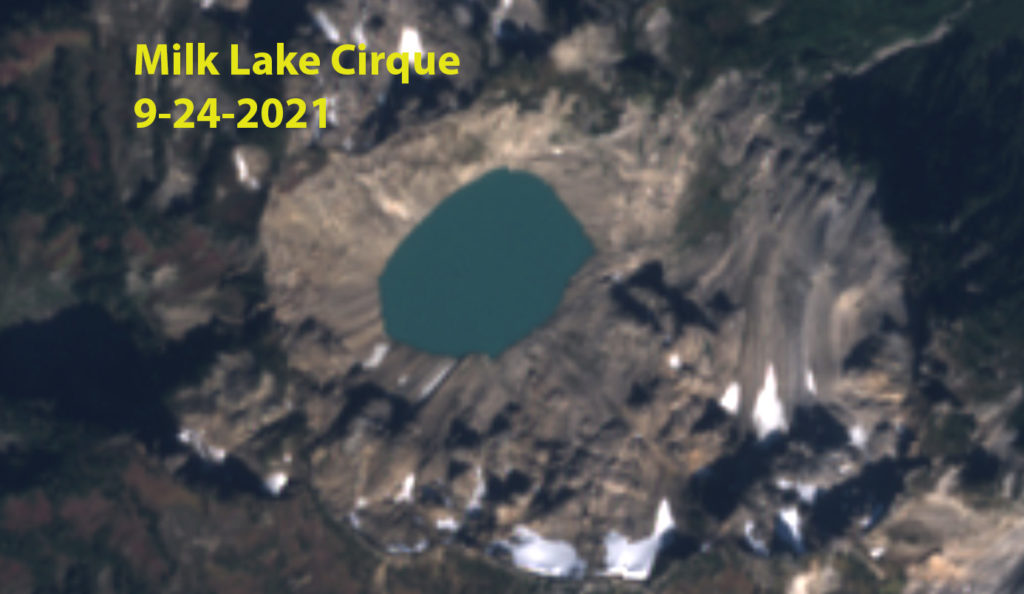

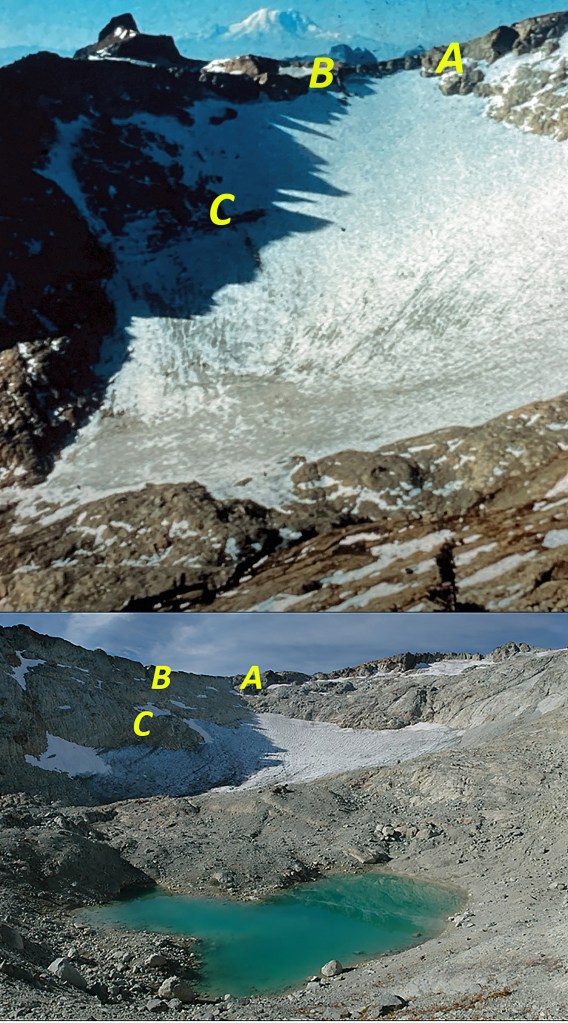

From 1984 to 1992, the glacier extended to within 15 m of the ridge on the south side of the basin. By 1995 this was no longer possible as the top of the glacier was retreating as fast as the bottom of the glacier. In 2006, the recession from this ridge was greater than the recession at the terminus. The glacier perimeter was surveyed in the low snow years of 2005 and 2015, identifying the glacier area to be 0.15 km2 and 0.110 km2, respectively. In 2015, the inventory for RGI noted an area of 0.106 km2. Annually, from 2021 to 2024, low snow cover allowed for mapping of the glacier perimeter during a rapid decline from 0.09 km2 to 0.03 km2. The area loss from 1986 to 2015 was 0.07 km2, which is less than the area loss from 2015 to 2023 of 0.08 km2. provides a photo comparison of the change from 1986 to 2023, with the people standing in the same location in each case. The observed area determined in the field from the GPS position locations closely matches the RGI inventory area in 2015 and the area derived from overlaying the points on Sentinel 2 imagery from August 2021 to 2024, which have a 10–30 m resolutionThis summer we observed a dozen holes that reached the bottom of the glacier 4-6 m below, indicating how thin the ice is. There is no movement, the size and thickness are too low to generate future movement, hence this is no longer a glacier. A glacier is a body of snow and ice that is moving, this requires a persistent thickness of 20-30 m, which is typically associated with snow/ice areas of ~50,000 m² or larger. As a glacier becomes thinner or smaller than this movement will not be sustained.

Table 1. The observed area of Ice Worm Glacier from field measurements. The area of Ice Worm Glacier from previous inventories and Sentinel 2 imagery.

| Year | Field Mapped Area (m2) | Validating Aerial/Satellite Image Area (m2) |

|---|---|---|

| 1958 | 190,000 (GLIMS) | |

| 1986 | 180,000 (±10,000) | Field Observation only |

| 1992 | 170,000 (±10,000) | Field Observation only |

| 2005 | 150,000 (±5000) | Field Observation only |

| 2015 | 110,000 (±5000) | 106,000 (RGI) |

| 2021 | 88,000 (±2000) | 90,000 (Sentinel) |

| 2022 | 68,000 (±2000) | Field Observation only |

| 2023 | 41,000 (±2000) | 40,000 (Sentinel) |

| 2024 | 32,000 (±2000) | 30,000 (Sentinel) |

We have measured discharge at a natrual weir below Ice Worm Glacier since 1986. Average August daily runoff has declined 60% by 2022.

Glacier Base Observations

Beginning in 2015, we routinely assessed how deep each moulin, crevasse or supraglacial stream channel was on the glacier. One measure of a glacier no longer being a glacier is when crevasse features and stream channels consistently reach the bedrock below the glacier. In 2023, we examined 24 of these features and each reached bedrock at depths of 2–10 m. These features were distributed widely across the glacier. There are undoubtedly limited areas of thicker ice. In 2024, we explored an ice cave that extended 250 m from the top of the glacier to the end of the glacier. The cave roof was 1–4 m above bedrock, and the roof was consistently less than 2 m thick allowing light to penetrate from the glacier surface into the cave. An extensive ice cave transecting the entire glacier such as this cannot exist in a current glacier because ice movement would lead to ice cave closure.

Streams channel reaching bedrock at base of Ice Worm Glacier.

Each year in mid-August, stream discharge has been observed immediately below the 1986 terminus position of Ice Worm Glacier at 11 a.m., 2 p.m. and 5 p.m. during the field visit. This stream is also fed by perennial snowfields and, before 2015, a small glacier. These observations are insufficient to quantify daily runoff, but because of the consistent timing and methods, do allow for comparison. The glacier is located on the dry side of the range and has not experienced rainfall during any of our field observation periods, which would contribute to stream discharge. From 1985 to 2002, streamflow was observed on 36 days, with the average discharge being 0.12 m3 s−1. From 2021 to 2024, discharge was observed on 6 days with the average discharge being 0.03 m3 s−1. This roughly 75% decline in August runoff is similar to the 60% loss in runoff modeled for the loss of small glaciers in basins in the Alps and observed when the Lewis Glacier, North Cascade Range was lost. The change in summer streamflow in Hyas Creek near our base camp is apparent, as it had been a challenging stream crossing to keep your feet dry until 2013, and now is a simple step across. There has also been a marked increase in algae coating the substrate of the stream with the lower flow, clearer and warmer water, which is expected.

Climate Drivers

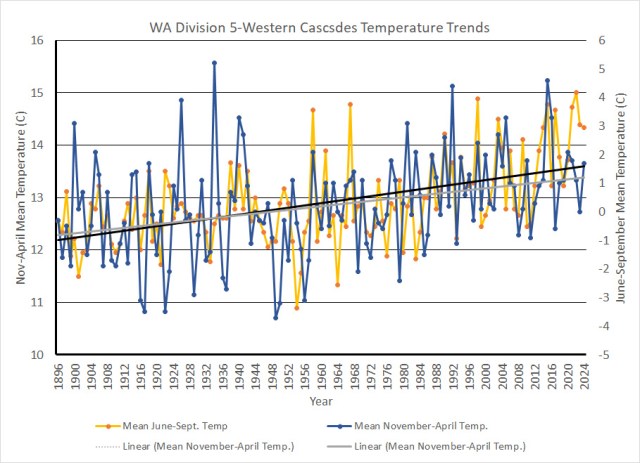

Trends in summer temperature at Western Cascade weather stations for the 1896 to 2024 period indicate that seven of the ten warmest melt seasons (June–September) have occurred since 2013. Melt season temperatures from 2014 to 2024 were 1.3 °C above the 1896 to 2022 mean. The long-term winter temperature trend from 1896 to 2024 has been 1.2 °C. From 2014 to 2024 winter temperatures were 0.9 °C above the long-term average, the warmest decadal period of the record.

During the 1896 to 2024 period from June to September, precipitation exhibited no significant trend. For the November–April (winter season) there was a 3% increase in precipitation from 1896 to 2024. From 2014 to 2024 winter precipitation averaged 1.68 m vs. the long-term average of 1.65 m. April 1 SWE from six long-term SNOTEL stations where April 1 SWE has a declining trend of 30% from 1946 to 2023, with a 10% decline since 1984. The April 1 SWE loss reflects increased melting of the snowpack or rain events during the winter season.This indicates that it is temperature rise that is driving the glacier mass balance loss, retreat and eventual disappearance of Ice Worm Glacier.