2017 Field Season Video

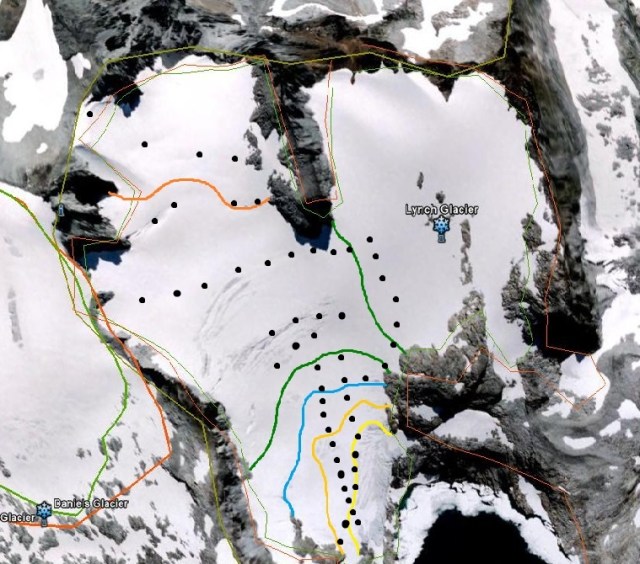

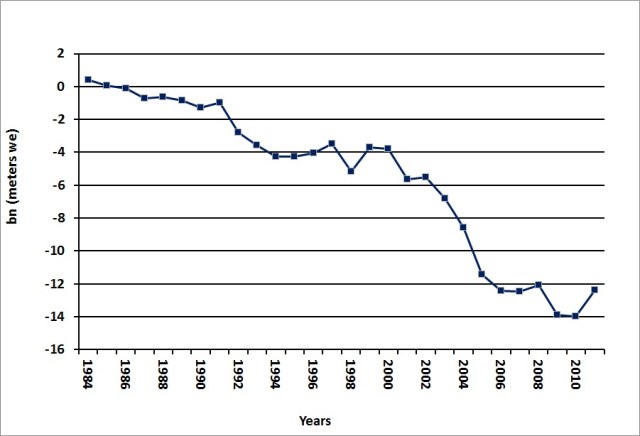

For the thirty fourth consecutive summer we headed into the field to monitor the continued response of North Cascade glaciers to climate change. In 1984 when I began this program we selected 10 key glaciers to monitor. Two of these have now disappeared. All the glaciers have retreated extensively and lost considerable volume. The mass balance loss is 19 m of water equivalent thickness, which is over 20 m of ice thickness loss on glaciers that averaged less than 75 m thick. This is significant with 25-30% of their entire volume lost. This project continues to monitor glacier loss and the runoff they provide. We also complete an annual inventory of ice worms on Sholes Glacier and mountain goats on Ptarmigan Ridge region. In 2017 our key project was a continue partnership with the Nooksack Indian Tribe monitoring glacier melt and runoff in the North Fork Nooksack River basin. We have not yet had the chance to determine the daily glacier discharge and the resultant contribution to the North Fork Nooksack River. The dry conditions of August certainly will lead to many days with more than 40% of the flow coming from glacier melt as was the case in 2015.

The snowpack on April 1st snowpack was 110% of normal, by June 1st, the snowpack was trending down steeply, but

remained well above the last four years and similar to 2012. Summer turned out to be the driest on record in Seattle and

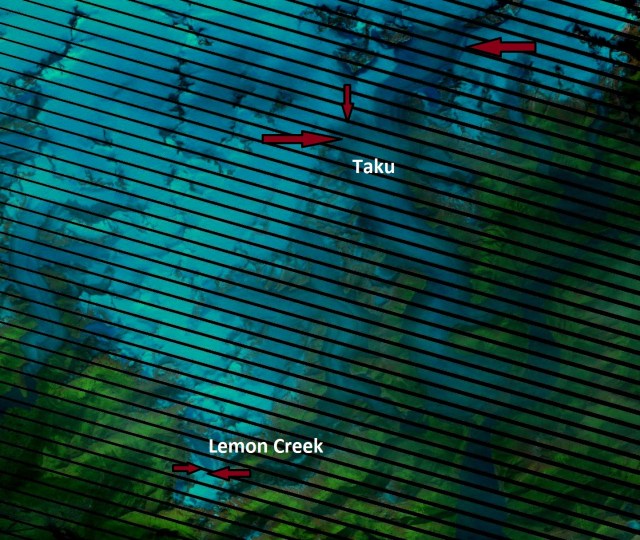

tied for the warmest for the June 21-Sept. 22nd period (KOMONews). In the mountains the overall melt season temperatures for May 1 through Sept. 30th was 0.15 C cooler than 2015 values, due to a cooler spring. The most striking feature of the field season was the forest fire smoke largely from British Columbia that obscured views most days.

Of the glaciers observed one had a significant positive balance, one a slight positive balance-essentially equilibrium and seven had negative mass balances. The two glaciers with the most positive balance were the Sholes and Rainbow Glacier, adjacent glacier on the north side of Mount Baker. The nearby Mount Baker ski area reported 860 inches of snow in 2017, significantly above average. Compared to other locations in the range this winter snowfall was a positive anomaly, that also was observed on the nearby glaciers. The snow water equivalent in multiple crevasses on Rainbow Glacier at 2000 m in early August was 3.8-4.1 m. On both Easton and Rainbow Glacier the mass balance gradient was steeper than usual. On Rainbow Glacier the mass balance was -3 m at 1500 m, 0 at 1700 m and +2.5 m at 200 m as summer ended. We also observed terminus retreat on every glacier. Retreat averaged 12 m in 2017, lower than in 2015 or 2016. More striking than retreat in some cases is thinning that reduces slope and frontal thickness. On Lower Curtis Glacier the terminus seracs are 15 m shorter than two years ago. On Columbia Glacier the lowest 200 m of the glacier has a slope that has declined by 5 degrees in the last three years and the glacier terminus has retreated 60 m in two years.