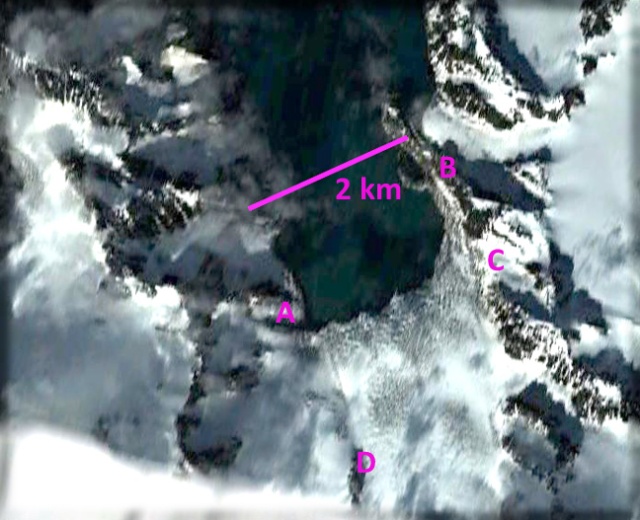

Arnesenbreen (A) and Bereznikovbreen (B) in 1990 and 2018 Landsat images. Red arrow is 1990 terminus location, yellow arrow the 2018 terminus location and purple dots the transient snowline.

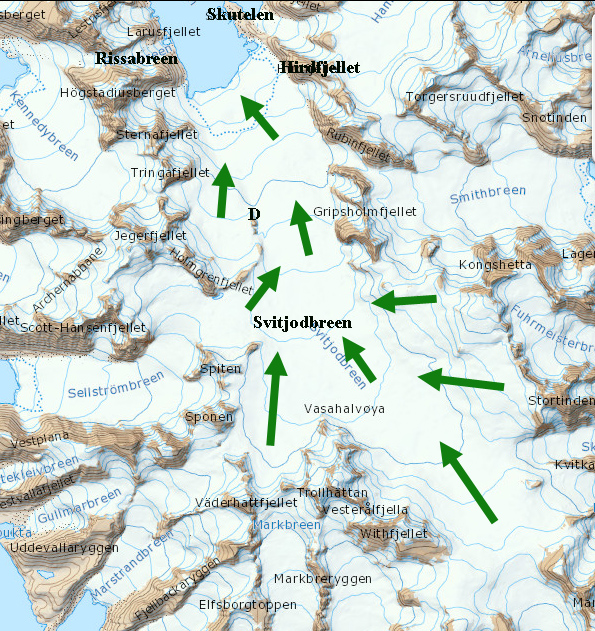

Arnesenbreen and Bereznikovbreen are glaciers in Svalbard on the east coast of Spitsbergen that in 1990 had a joint calving front near Kapp Murchison. Blaszczyk et al’s (2009) analysis identified 163 Svalbard glaciers that are tidewater with the total length calving ice−cliffs at 860 km for the 2001-2006 period. They observed that 14 glaciers had retreated from the ocean to the land over the last 30–40 year period. Some of these are surging glaciers, which are common in Svalbard. Arnesenbreen was observed to surge in the 1930’s and in 2018 a surge was observed that was initiated from its terminus, which is a more unusual type of surge (Holmund, 2018). Sevestre et al (2018) document mechanisms that help generate terminus initiated surges, include tidewater retreat from a pinning point and/or crevasses allowing meltwater rainwater to access the bed. The surge generated considerable crevassing that extended from the tidewater terminus to an elevation of 300 m, 5 km inland of the terminus. Here we examine the behavior of these glaciers using Landsat imagery from 1990-2018.

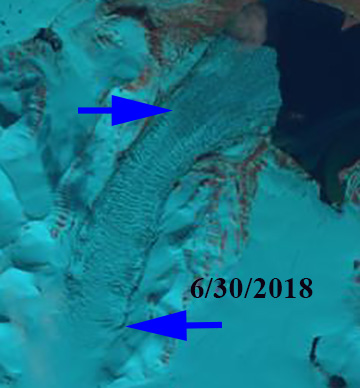

In 1990 Arnesenbreen-Bereznikovbreen had a shared 5 km long tidewater front. The transient snowline in this July image is at 200 m. The glacier terminus reach is not extensively crevassed. In 2002 the two glaciers are separating at Point 1 each having retreated ~400-500 m, crevassing remains limited. The transient snowline in 2002 is at 300 m. By 2014, Arsenenbreen has retreated 1400 m since 1990 and crevassing remains limited. The transient snowline is at 300 m, though there is a saturated zone of snowpack above this line, that suggests extensive melt up to 500 m. In 2018 the surge crevassing was most apparent in the April image of Holmund (2018). On June 30 the extensive crevassing is still evident, particularly in the 200-250 m elevation band near Point 2, but is reduced from April in the terminus zone near Point 1. By July 21 the image indicates much reduced calving in the terminus zone of the glacier. Sevestre et al (2018) note a pattern of terminus initiated surge progression, “Upward migration of the surge coincided with stepwise expansion of the crevasse field.” This is exactly what is seen at Arnesenbreen, we are also seeing the surge terminating with calving reduction at the terminus first. The short lived nature of the surge indicates the limited impact on the longer term retreat. The surge did not lead to a reconnection with Bereznikovbreen. Bereznikovbreen has retreated 700-800 m since 1990 and Arnesenbreen has retreated ~1500 m from 1990-2018.

The ongoing retreat here is like that of Svalbard glaciers in general including surging glaciers (Nuth et al 2013). Strongbreen Glacier has separated from key tributaries. The ongoing retreat has prompted the question on other surging Svalbard glaciers, can the glaciers continue to surge? On Fridtjovbreen it appears a future significant surge is unlikely. For Arnesenbreen the terminus reach below 150 m is where the glacier expands laterally and is an area of reduced slope. This configuration remains and would allow further surges unless further retreat of more than ~1500 m occurs.

Arnesenbreen (A) and Bereznikovbreen (B) in 2002 and 2014 Landsat images. Red arrow is 1990 terminus location, yellow arrow the 2018 terminus location and purple dots the transient snowline.

Arnesenbreen in Landsat image from6/3/2018 indicating zone of most extensive crevassing.

Arnesenbreen (A) and Bereznikovbreen (B) in Toposvalbard map and recent Landsat imagery from Toposvalbard.