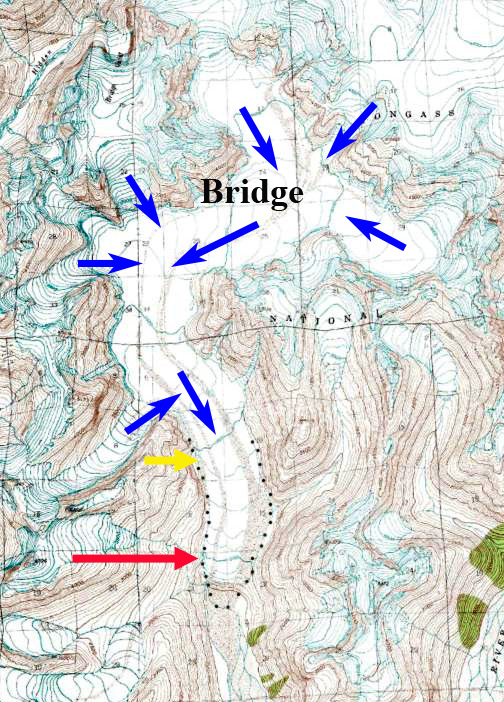

Meade Glacier in Landsat images from 1986 and 2018. The red arrow indicates the 1986 terminus, pink arrow the 2014 terminus, yellow arrow the 2018 terminus, orange arrows tow tributaries to Meade Glacier and the purple dots the snowline.

Meade Glacier drains the northwest portion of the Juneau Icefield, with meltwater entering the Katzehin River and then Chilkoot Inlet. The glacier begins in British Columbia and ends in Alaska. Here we use Landsat imagery to examine changes in the glacier from 1986 to 2018. The glacier experienced a slow continuous retreat from 1948 to 1986 of 400 m, with the glacier ending on an outwash plain.

In 1986 the terminus is indicated by a red arrow, the snowline is at 1250 m in 1986, there is no evident lake at the terminus of glacier just an expanding outwash plain. Both tributaries from the south, orange arrows, are 750 m+ wide where they join Meade Glacier. By 2004 a 400 m long proglacial lake has formed at the terminus. The two tributaries from the south, at the orange arrows, no longer are connected to the glacier. The snowline is at 1450-1500 m. In 2014 the proglacial lake is 3.5 km long, the entire lower 2.5 km of the glacier has collapsed since 2004. There is still considerable relict ice floating in the lake. There is a substantial lake along the southern margin of the glacier where a tributary streams enters the main valley. This indicates the glacier will quickly retreat to this point by further collapse into the lake. The snowline in 2014 is at 1450 m on Aug. 2, the date of the imagery, the high snowline ensures continued mass loss and glacier retreat. By 2018 Mead Glacier has retreated 4.1 km since 1986. The snowline is at 1450 m on October 2, when fall snow should have already begun. A third tributary entering the glacier from the east at 1200 m no longer reaches the main stem. Based on surface slope changes the glacier appears to be within 1 km of the inland limit of the proglacial lake. The inland limit should be near the prominent bedrock knob on the south side of the glacier a short distance inland of the current terminus. When this is reached the glacier retreat will be reduced. The retreat parallels that of most Juneau Icefield glaciers including the next glaciers to the south Field Glacier and Gilkey Glacier. The glacier shares a divide with Warm Creek Glacier that terminates in British Columbia that is also retreating rapidly in an expanding lake.

Meade Glacier in Landsat image from 2004. The red arrow indicates the 1986 terminus, pink arrow the 2014 terminus, yellow arrow the 2018 terminus, orange arrows tow tributaries to Meade Glacier and the purple dots the snowline.

Meade Glacier in Landsat image from 2014. The red arrow indicates the 1986 terminus, pink arrow the 2014 terminus, yellow arrow the 2018 terminus, orange arrows tow tributaries to Meade Glacier and the purple dots the snowline.

Meade Glacier in Landsat image from 2018. The red arrow indicates the 1986 terminus, pink arrow the 2014 terminus, yellow arrow the 2018 terminus, orange arrows tow tributaries to Meade Glacier and the purple dots the snowline.