This is a portion of the island emerging from beneath the terminus with the 20-50 m high ice front in July 2023, the main portion of the island extends to the left and then out from the glacier. (Bischke/Biner/Bessen/Klemmensen)

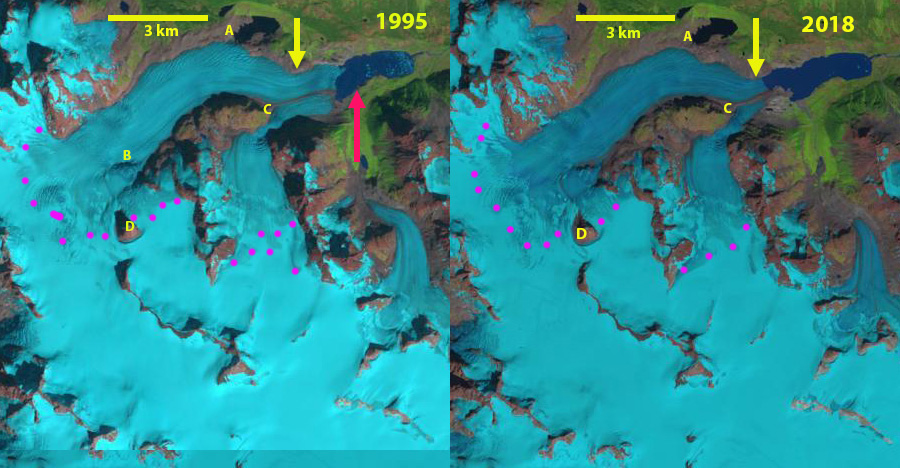

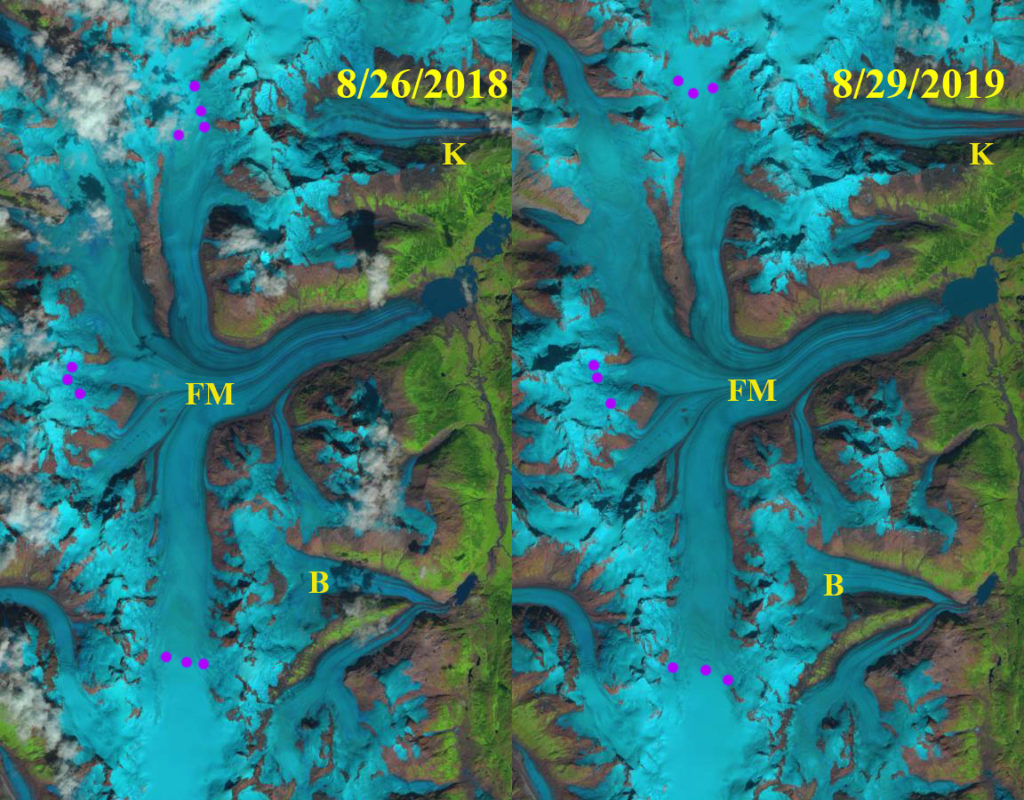

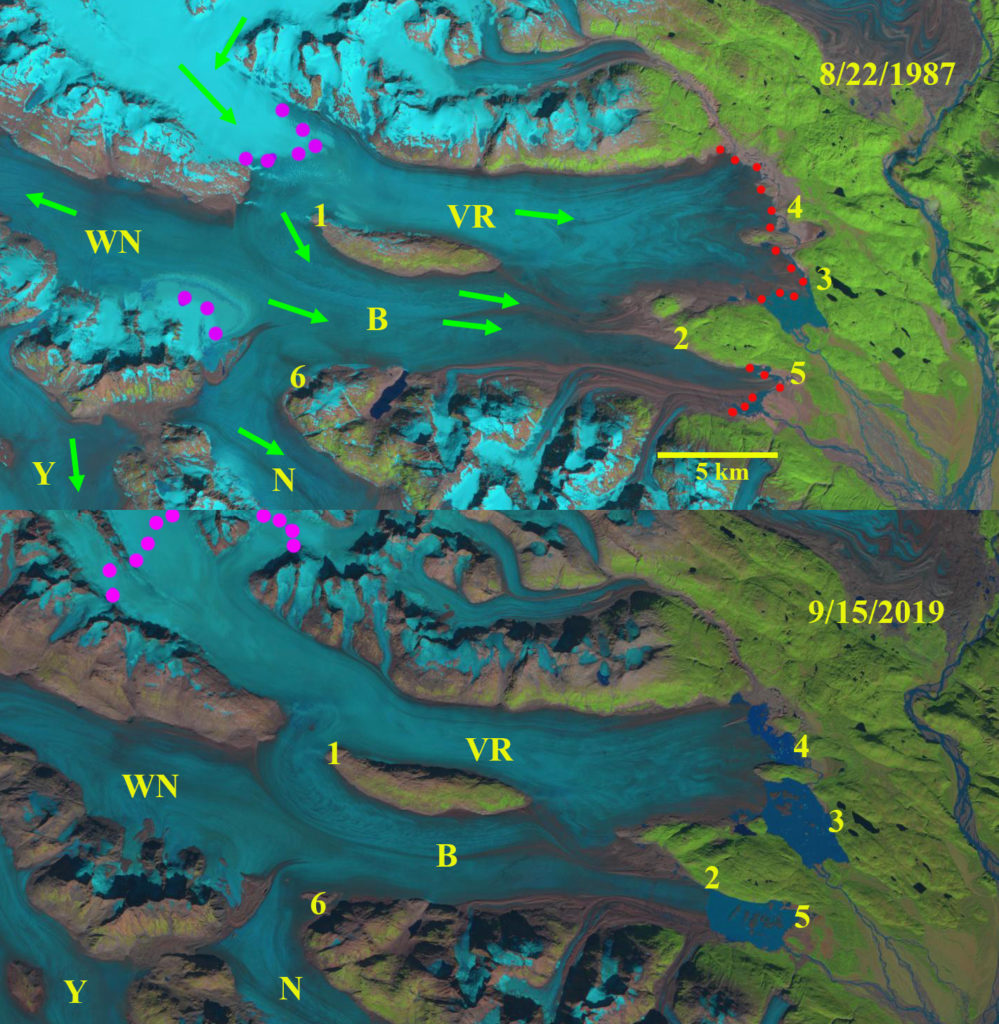

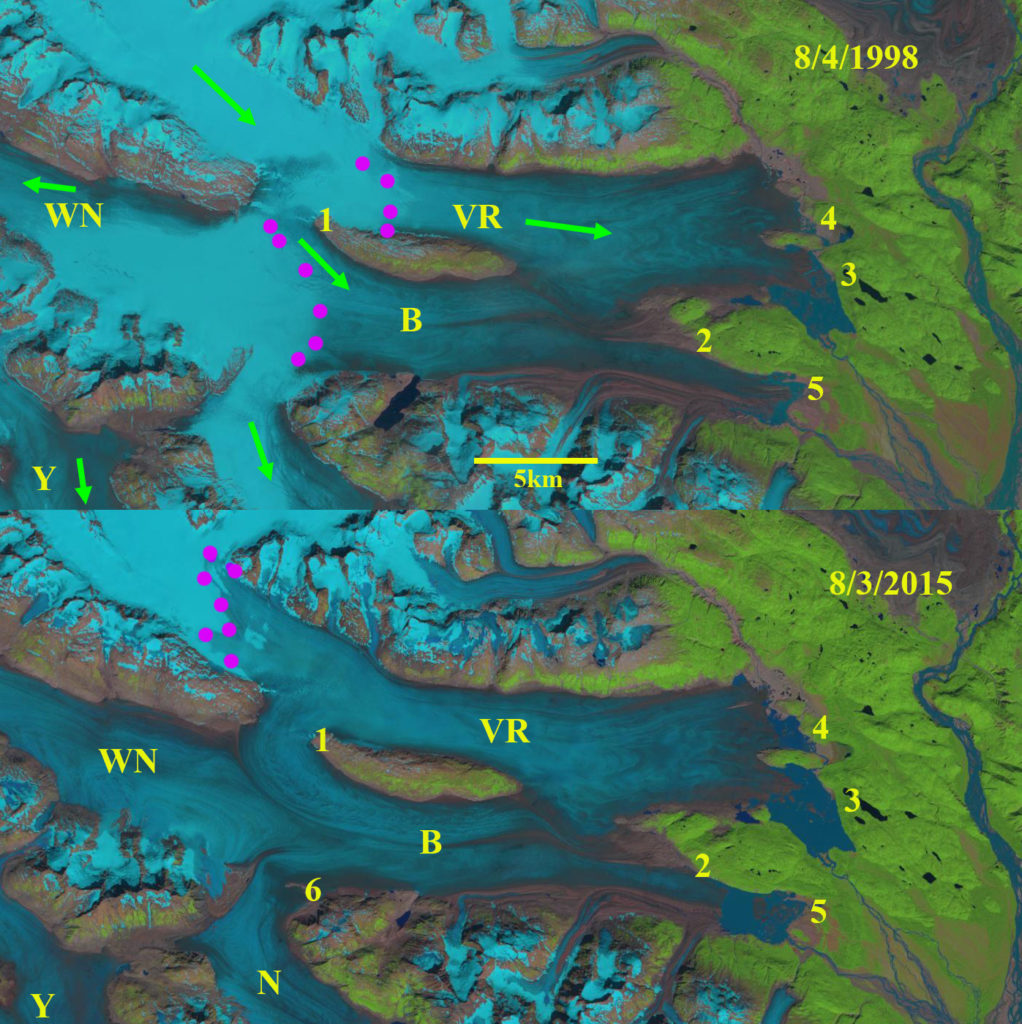

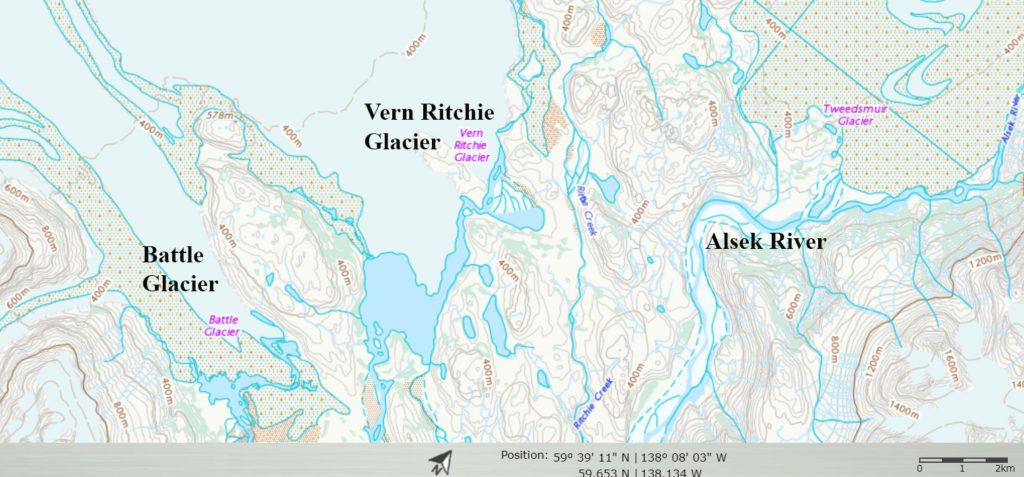

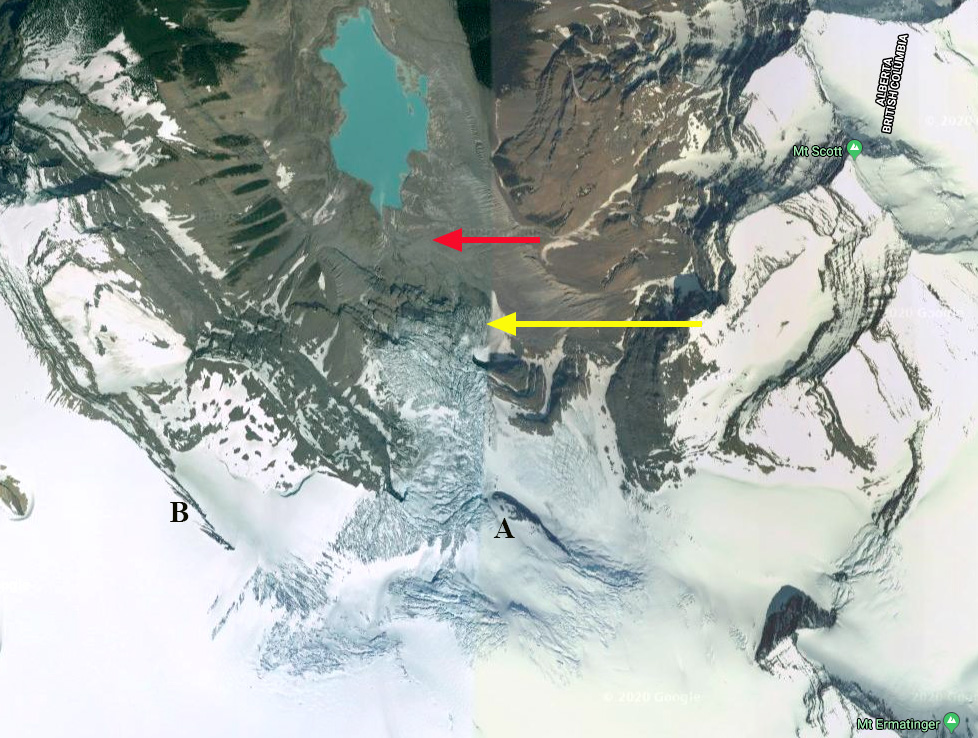

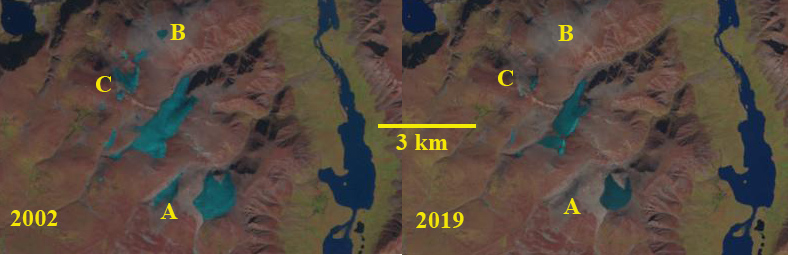

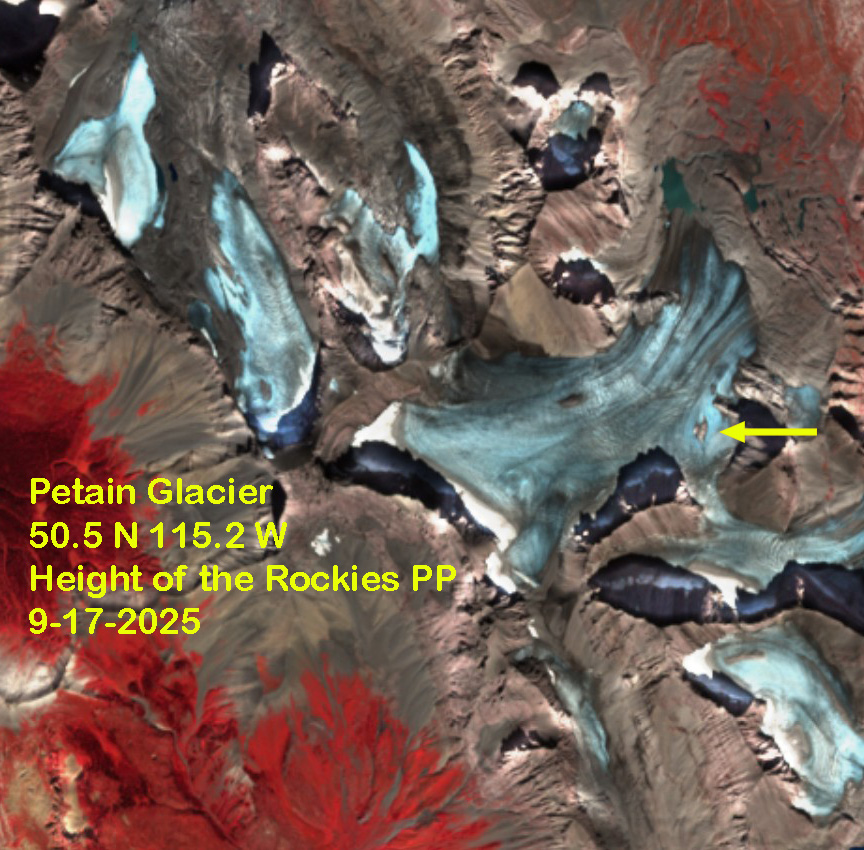

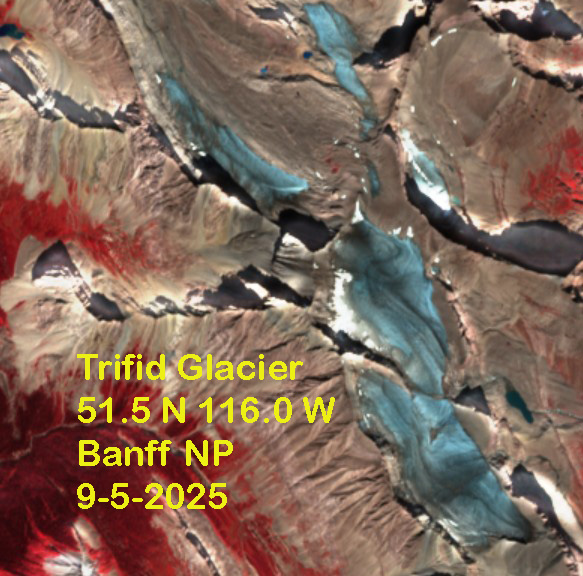

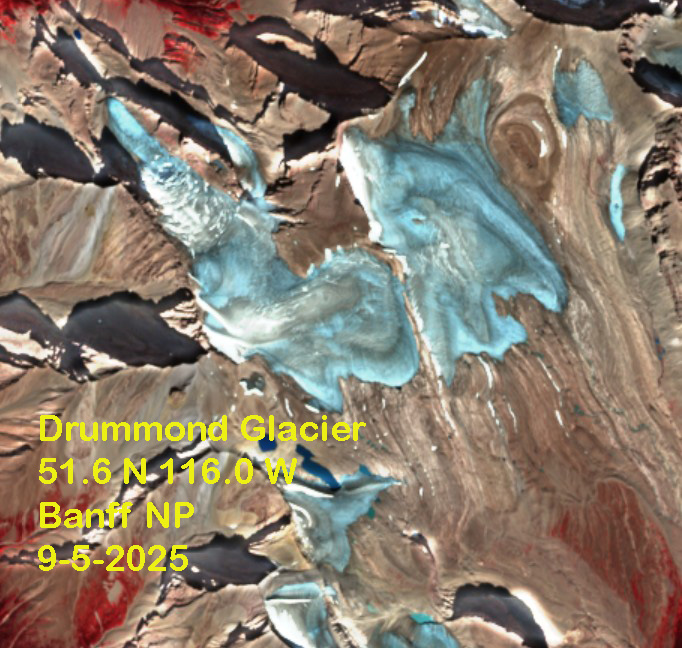

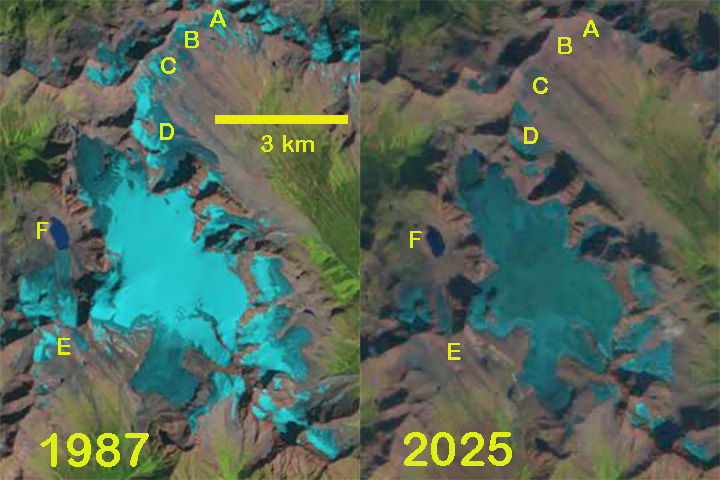

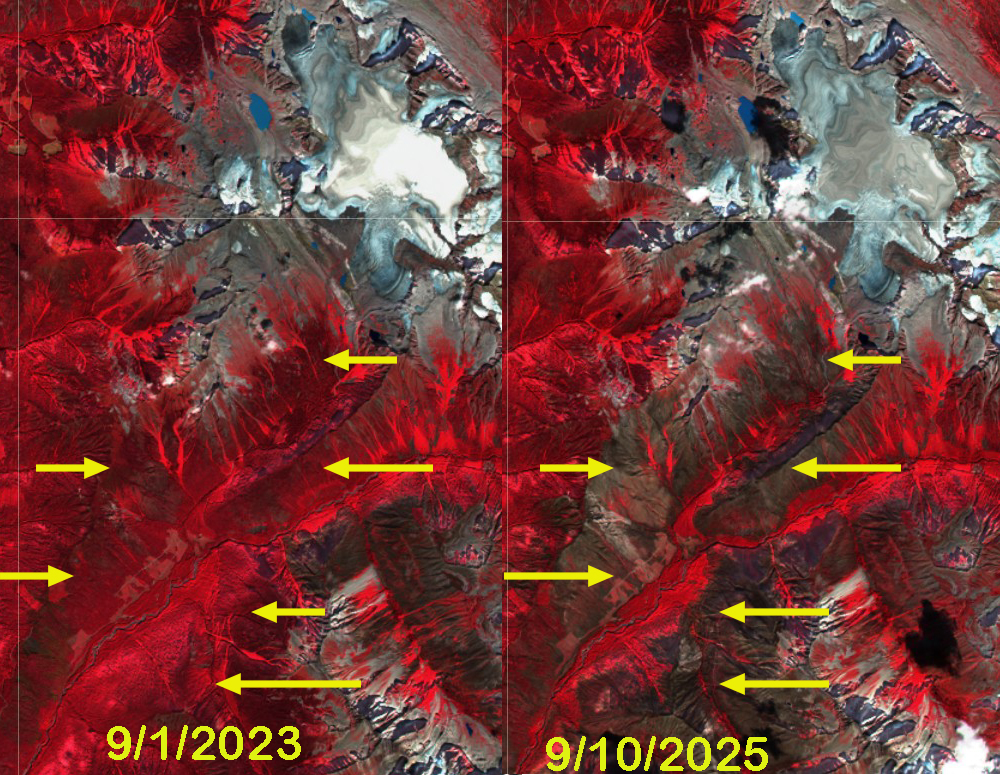

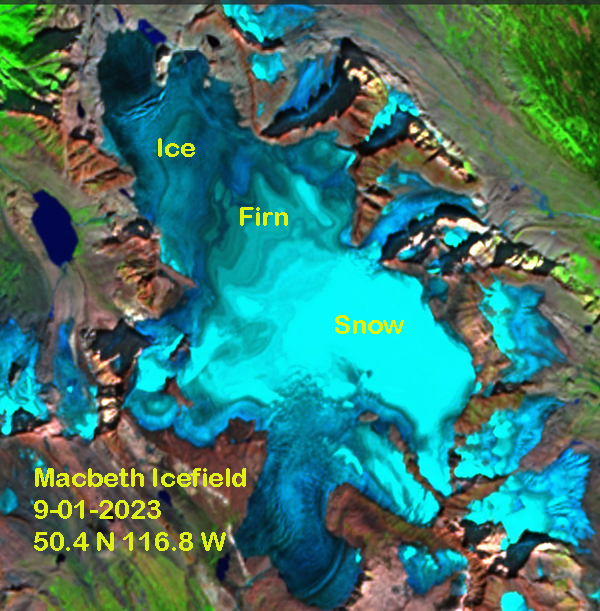

Coronation Glacier is the largest outlet glacier of the Penny Ice Cap on Baffin Island. The glacier has an area of ~660 square kilometers and extends 35 km from the edge of the ice cap terminating in Coronation Fjord. Retreat from 1989 to 2023 has been 1050 m on the northern side of the fjord and 900 m on the south side of the fjord. The average retreat of 975 m in 33 years is ~30 m/year, much faster than the 1880-1988 period. Locations 1-9 are tributaries that have each narrowed or retreated from the main stem of the glacier. I reported on a new island forming at the terminus in 2016, and I have been hoping to identify someone who would visit the island. The island now has an area of 0.25 km², its character is evident in images below. Amanda Bischke reached out on behalf of a four person climbing team heading into the area this summer. In mid-July the team had reached the front of the glaciers and over the next 20 days explored the glacier and its tributary. Here I analyse images taken by the team of Amanda Bischke, Shira Biner, Noah Bessen and James Klemmensen in conjunction with Sentinel images. One striking aspect of the Sentinel image from August 16, 2023 is how the snowline is on the ice cap feeding tributary 1-3 at 1500 m. This has become a common theme, and is resulting in less flow from the ice cap down these tributaries leading to detachment. Tributary 1, 3 and 6 have separated from the main glacier, while Tributary 2,4,7 and 9 have detachments nearly or completely severing the glacier enroute to the main glacier.

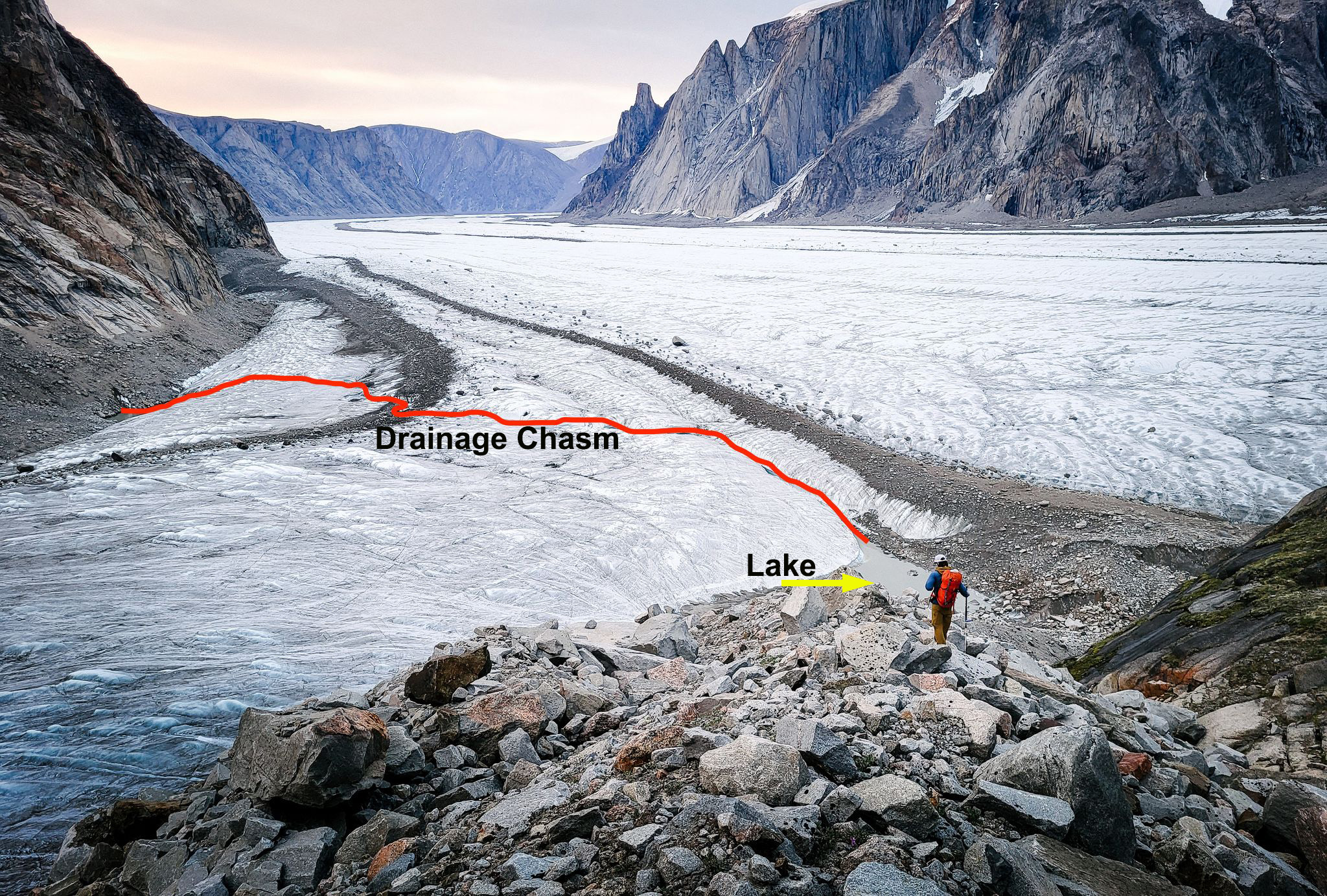

I appreciate the collaboration with the climbing party who have posted an initial report, I will update when further reports are published. Of their four first ascents, The Drawbridge was a visually compelling line to me. If you are heading out into a seldom visited glaciated area on a climbing expedtion reach out and see what would be valuable to observe. We can see overall changes from satellite imagery, but not the details. Two examples here are what the surface of the island is composed of, sand and small rocks in this case, or a developing detachment such as at the chasm are not evident from satellite imagery.

As the glacier retreats the Island continues to expand from 2017-2023. The tributaries I hoped the climbing team could document where possible if they were still attached.

The climbing team visiting the oldest part of the island looking toward newest part (Bischke/Biner/Bessen/Klemmensen)

The climbing team visiting the oldest part of the island looking toward newest part (Bischke/Biner/Bessen/Klemmensen)

A view of the island from the north side of Coronation Glacier (Bischke/Biner/Bessen/Klemmensen)

Sentinel image of the expanding island at the Coronation Glacier terminus in Sentinel images.

Tributary 1 detached from main glacier, note high snowline (Bischke/Biner/Bessen/Klemmensen)

Tributary 2 has a detachment point before the main glacier, though relict ice below still connects. Note snow is only retained at very top of ice cap with a month of melt season left. (Bischke/Biner/Bessen/Klemmensen)

Tributary 6 is still connected all the a detachment is occurring halfway from ice cap to main glacier. (Bischke/Biner/Bessen/Klemmensen)

Tributary 7 and 8 are still connected, though 7 has a detachment now (Bischke/Biner/Bessen/Klemmensen)

Tributary 7 and 8 are still connected, though 7 has a detachment now (Bischke/Biner/Bessen/Klemmensen)

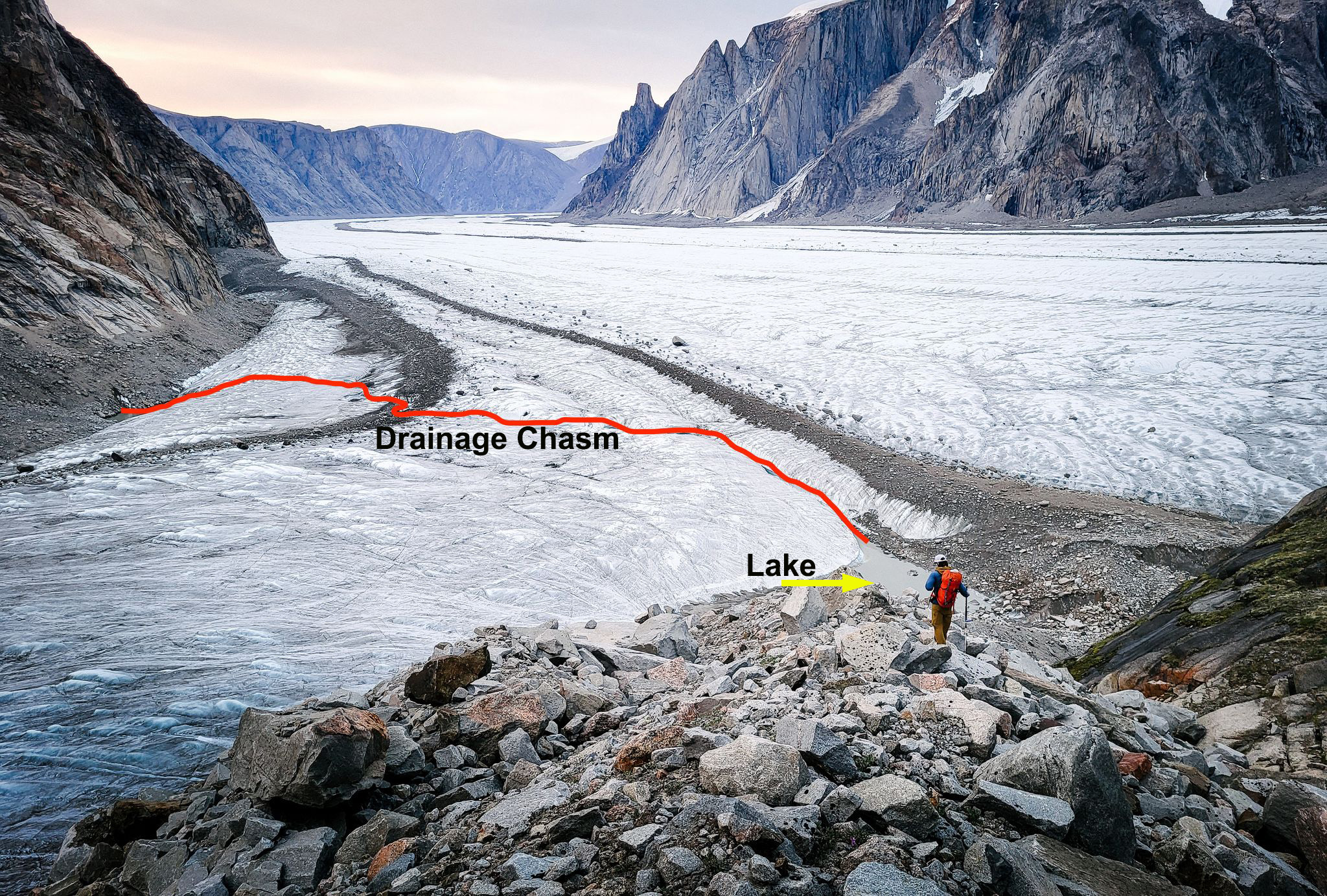

Triburary 9 had an interesting barrier to the climbers a deep chasm carved by an outlet stream draining meltwater, some of which had pooled in the lake shown. (Bischke/Biner/Bessen/Klemmensen)

The climbing team visiting the oldest part of the island looking toward newest part (Bischke/Biner/Bessen/Klemmensen)

The climbing team visiting the oldest part of the island looking toward newest part (Bischke/Biner/Bessen/Klemmensen)

Tributary 7 and 8 are still connected, though 7 has a detachment now (Bischke/Biner/Bessen/Klemmensen)

Tributary 7 and 8 are still connected, though 7 has a detachment now (Bischke/Biner/Bessen/Klemmensen)