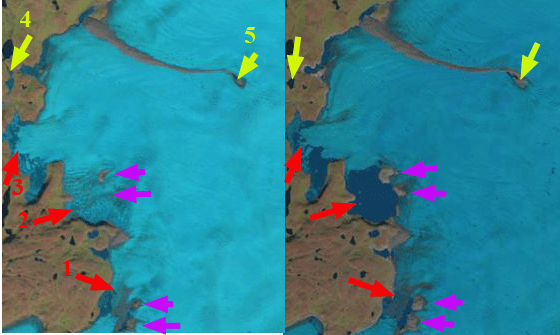

Upernavik Glacier in Landsat images from August 2000 and August 2016. Each Point is at the same location in both image, and the changes are noted in the discussion below. The same locations are also identified in the July 2001 and Aug. 2016 image below.

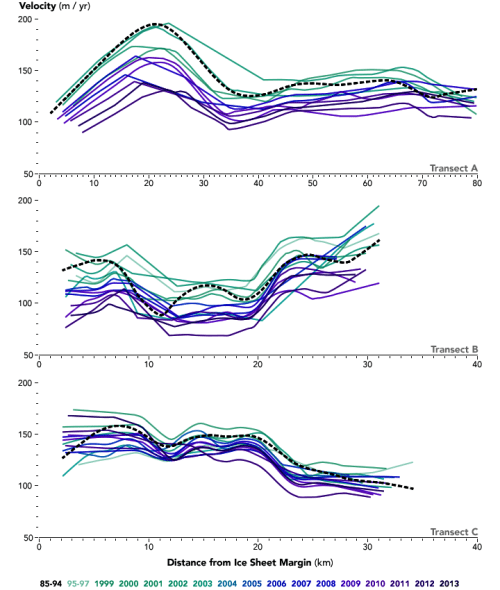

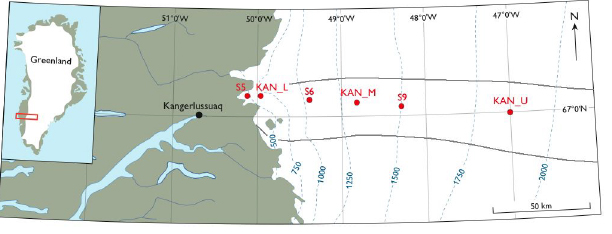

Upernavik Glacier is on the NW Greenland Coast the next major outlet north of Rinks Glacier. Today the glacier has four separate main calving termini, that was a single terminus until 1980. The retreat of this glacier is exposing new islands, nunataks etc that is examined in Landsat images from 2000 to 2016. Howat and Eddy (2011) observed the terminus change of 71 outlet glaciers in NW Greenland from 2000-2010 and found that 98% had retreated. The retreat has occurred irrespective of the different characteristics of various glaciers (Bailey and Pelto, SkS). Box and Decker (2011) note that ice loss for Upernavik Glacier’s combined termini was 7.9 square kilometers per year from 2000-2010. Larsen et al (2016) observed asynchronous changes in dynamic behavior of four outlets of Upernavik between 1992 and 2013. Velocities were stable for all outlets at between 1992 and 2005. The northernmost glacier began acceleration and thinning in 2006 -2011. The second most northerly outlet began acceleration and thinning in 2009 and this continued through at least 2013. The southern glaciers showed little change. They observed that the southernmost which is the focus here underwent a small deceleration between 1992 and 2013. Velocity data for the 1999-2014 period of the southernmost outlet is available using an online map browser (Rosenau et al; 2015), indicates the highest velocity of the southernmost branch occurred in 2013 and 2014, which would also lead to enhanced thinning. Moon et al (2014) observed the velocity of the southernmost arm of Upernavik to have a velocity of 2-3 km per year with a modest seasonal velocity fluctuation of ~15%. They note that Upernavik Glacier is a type 2 glacier, exhibiting relatively stable velocity from late summer through winter into spring, followed by a strong early summer speedup and midsummer slow down.

Here we examine the changes from 2000 to 2016 at ten locations near the front of the southern most of the main outlets of Upernavik Glacier. This reveals the formation of new islands, exposure of the former glacier bed and expansion of nunataks.

Point 1: In 2000 and 2001 this is a nunatak just below the number that is separated by 500 m of glacier from the edge of the ice sheet. In 2016 this point is a knob at the edge of the glacier.

Point 2: This is an area of bedrock, just below the number where the glacier terminates in 2000 and 2001. In 2016 this is an island that is 2.5 km from the ice front.

Point 3: In 2000 and 2001 this indicates a small area of bedrock just above the number, that is less than 300 m across. In 2016 this is a large area of bedrock that is over 1 km across and is merging with other bedrock areas near the glacier front.

Point 4: Is a small area of bedrock just west of the number that is 2 km from the ice front in 2000 and 2001. In 2016 this area of bedrock has merged with bedrock at the terminus of glacier and extends 3 km from the ice front inland.

Point 5. This is a region surround the number that is under ice in 2000 and 2001, there is a narrow rib of rock extending from the edge of the glacier to Point 5. In 2016 a large area of the former glacier bed is exposed with numerous streamlined bedrock features.

Point 6 is a small area of bedrock in 2000 and 2001 that is 2 km from the glacier edge. In 2016 this has become an area that extends 1 km from north to south and has a narrow bedrock connection to the glacier edge. The former glacier bed will continue to be expose between Point 5 and Point 6.

Point 7: In 2000 and 2001 this point marks the ice front where a medial moraine reaches the terminus. In 2016 this is an area of bedrock that will either become a new island or merge with bedrock at Point 1.

Point 8: Just west of the number in 2000 and 2001 is a single small outcrop of bedrock less than 200 m across. In 2016 the area of bedrock extends south for 1 km from the main nunatak that is also expanding.

Point 9: In 2000 and 2001 this location is covered by ice 500 m north of a nunatak. In 2016 a new bedrock knob has emerged that will soon join the main nunatak.

Point 10: In 2000 and 2001 this location is covered by ice 5 km from the ice front. In 2016 a one kilometer long bedrock rib has emerged due to glacier thinning.

The retreat of this glacier exposing new islands and nunataks is repeated at Steenstrup Glacier, Alison Gletscher and Kong Oscar Glacier

Upernavik Glacier in Landsat images fromJuly 2001 and Aug. 2016. Each Point is at the same location in both image, and the changes are noted in the discussion above.

View of the Upernavik four main calving fronts. The focus here is on what is deemed the south trunk. This is from the University of Dresden velocity map portal.