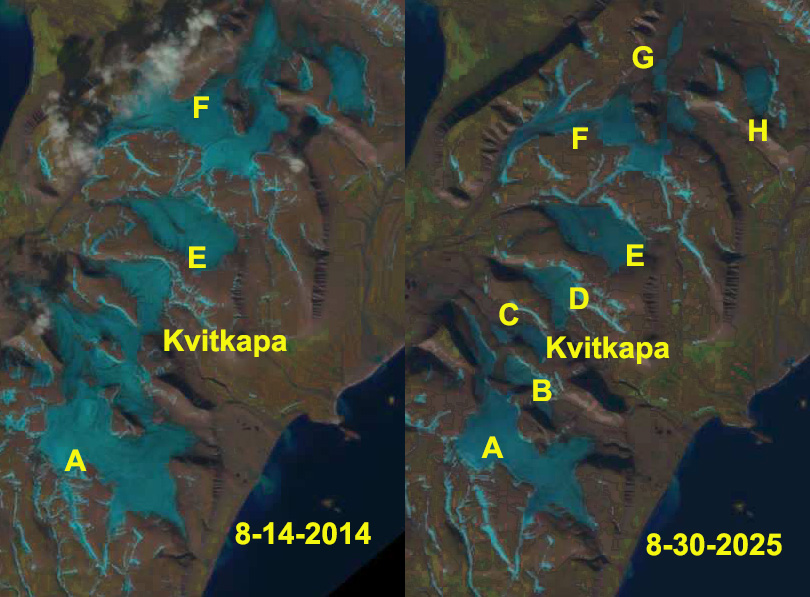

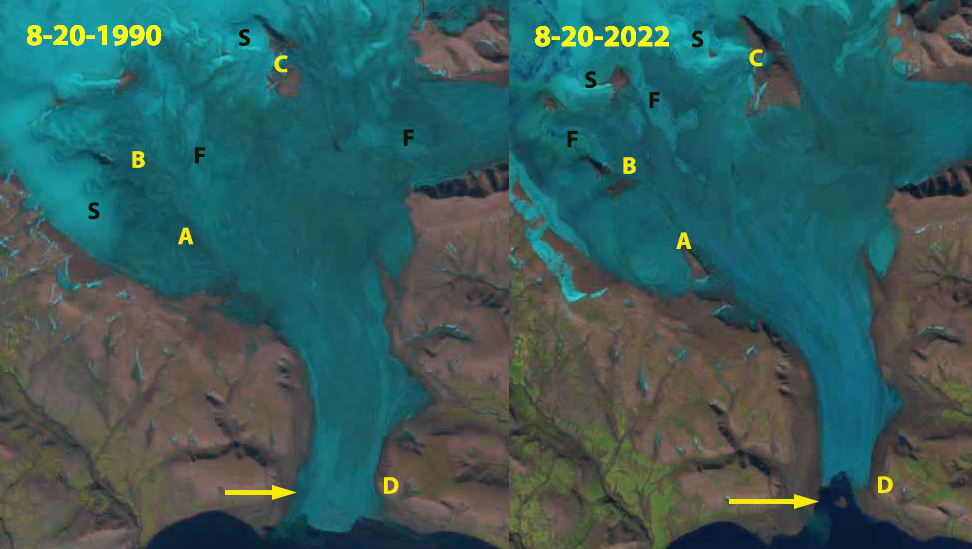

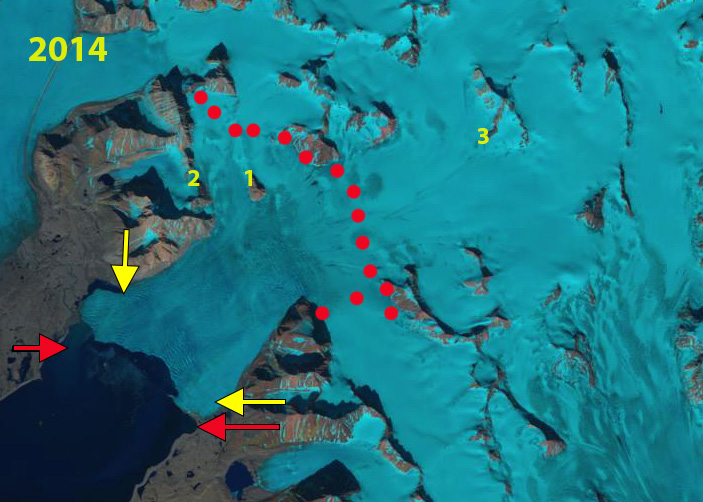

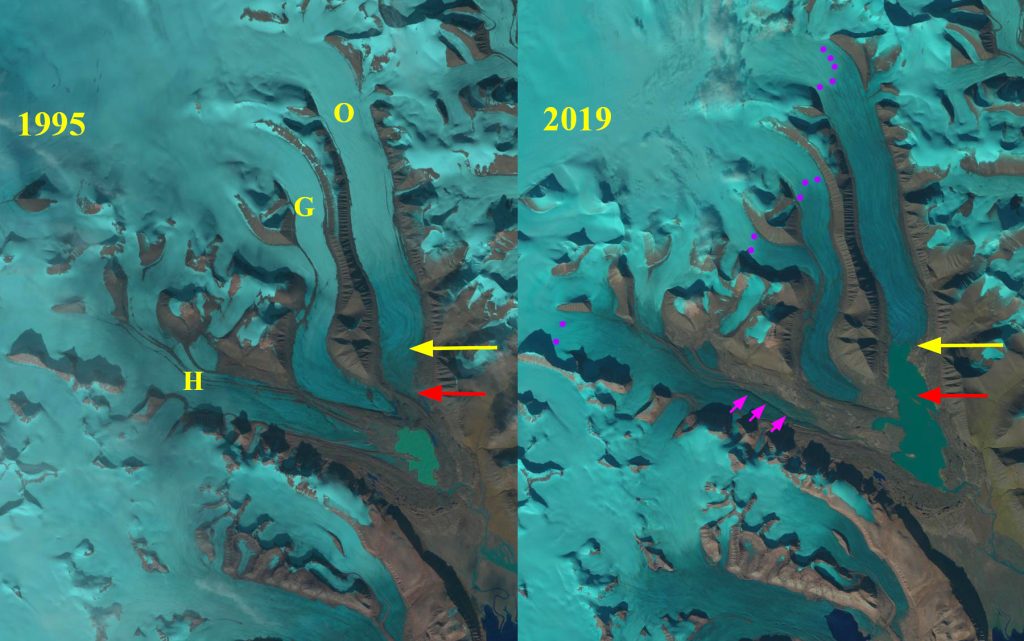

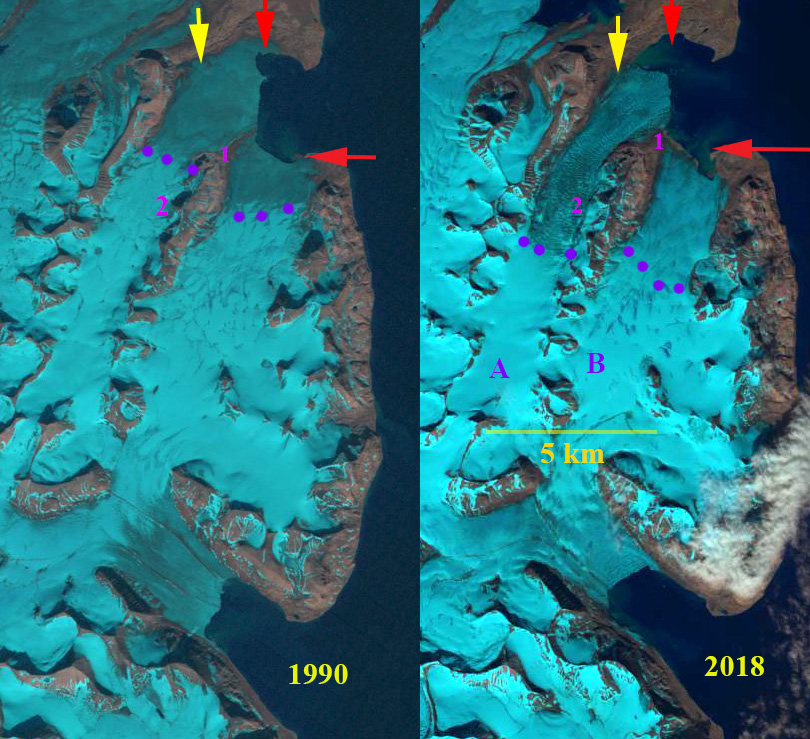

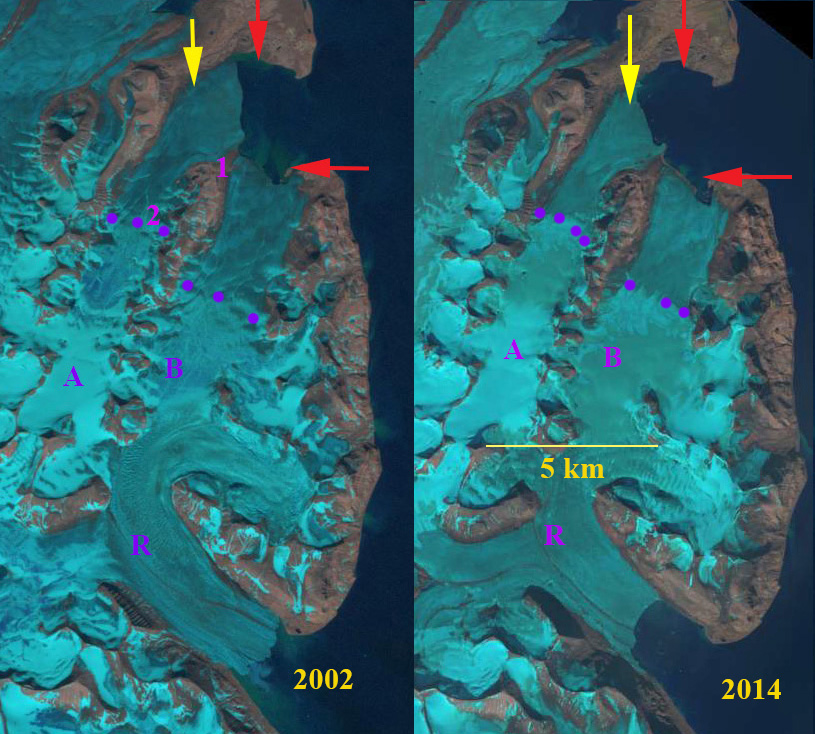

Langjokulen (La), Kvitisen (Kv), Bergfonna (Be) and Blaisen (Bl) ice caps on Edgeøya in Landsat images from 1990 and 2022. Two years of excepational melt where the ice caps lost all of their snow cover. Here the changes in the ice caps are reviwed at Points A-J.

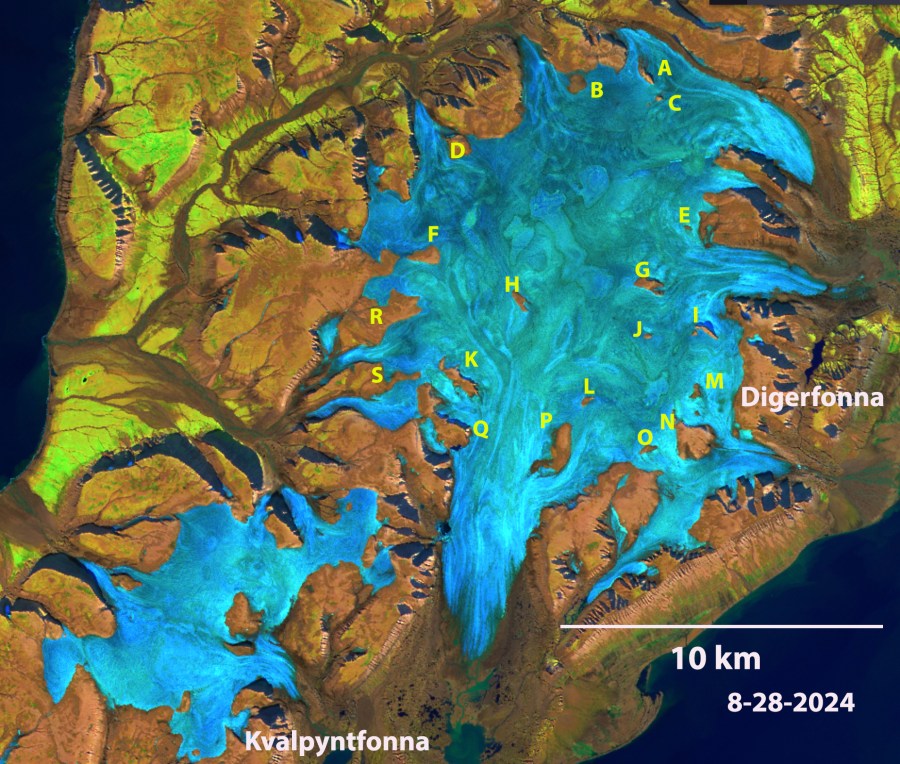

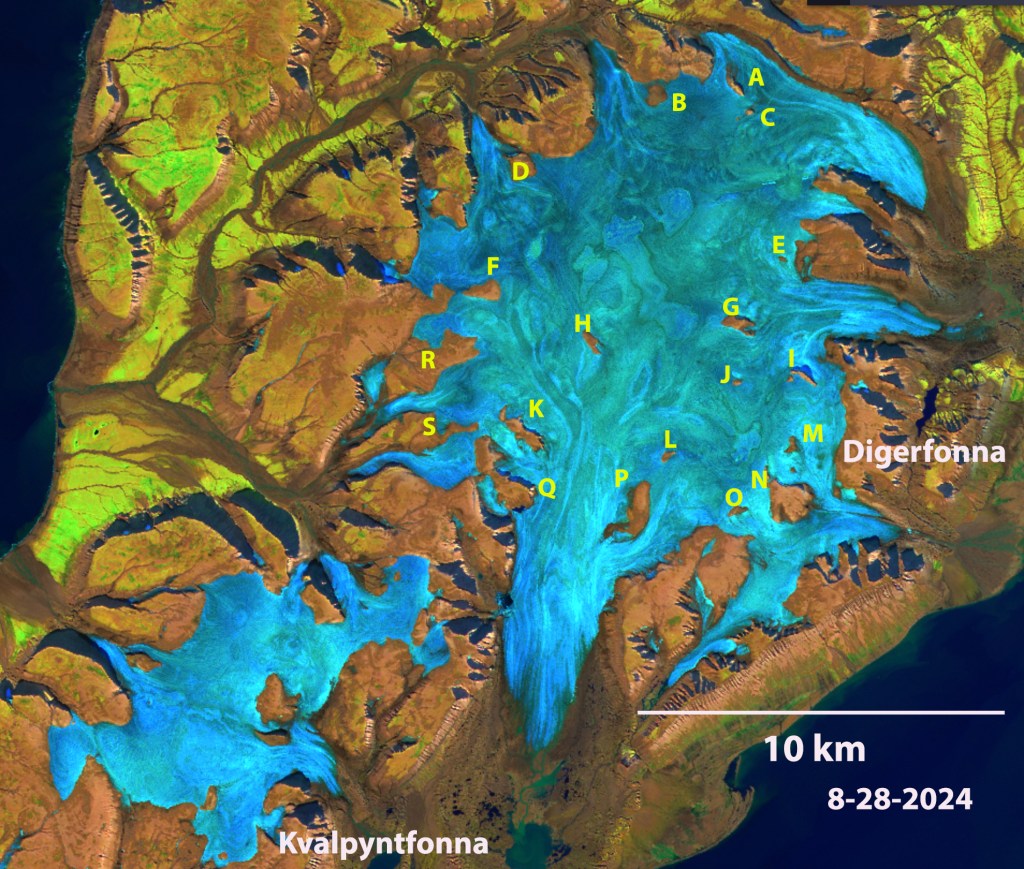

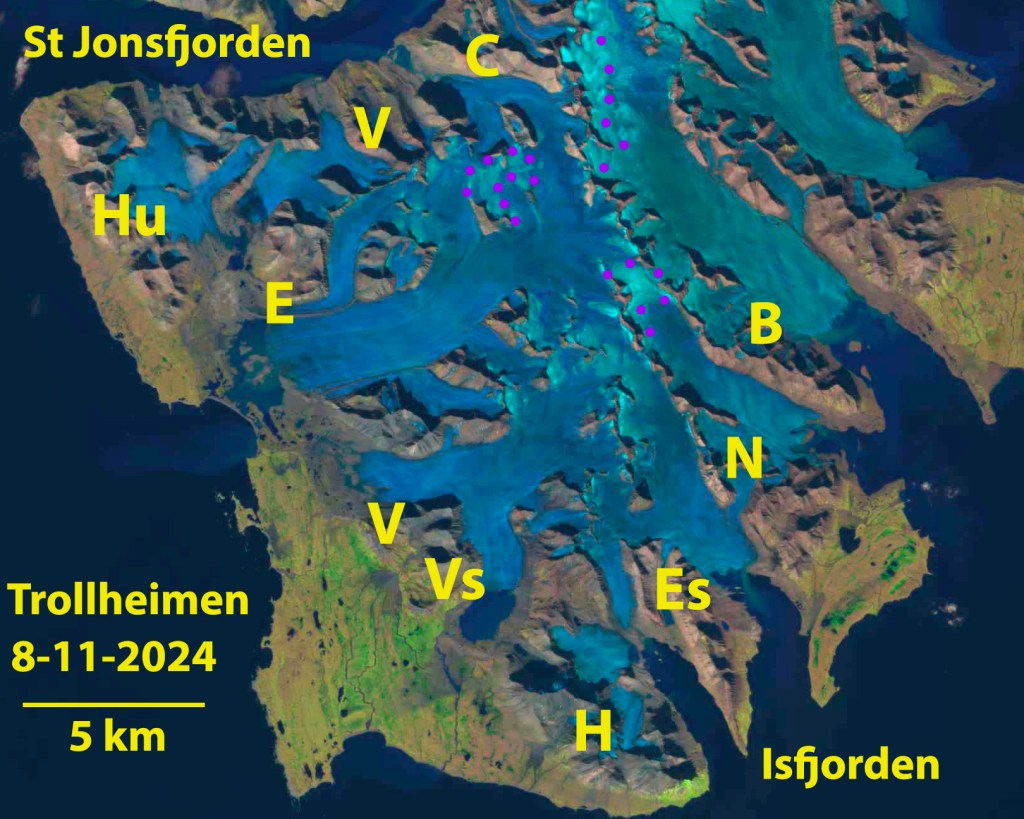

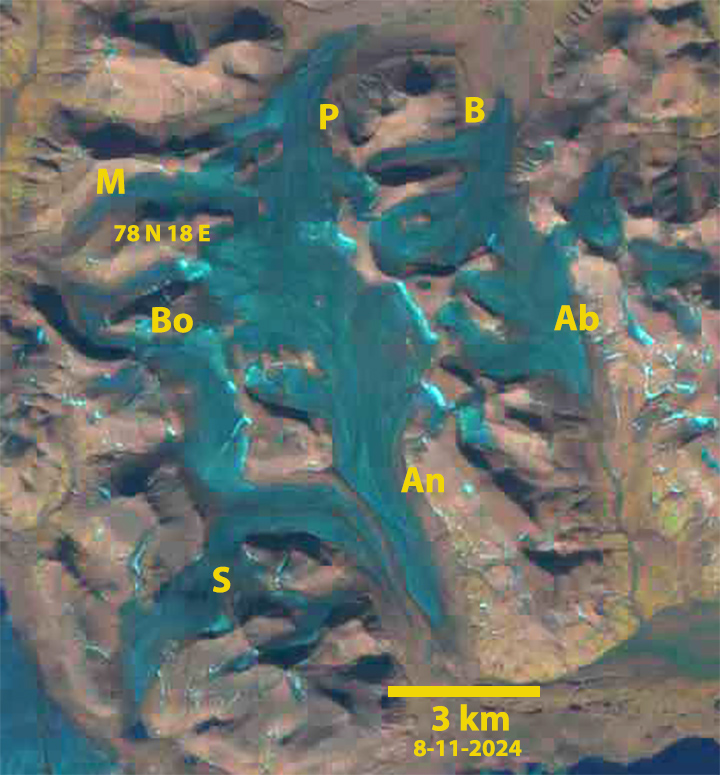

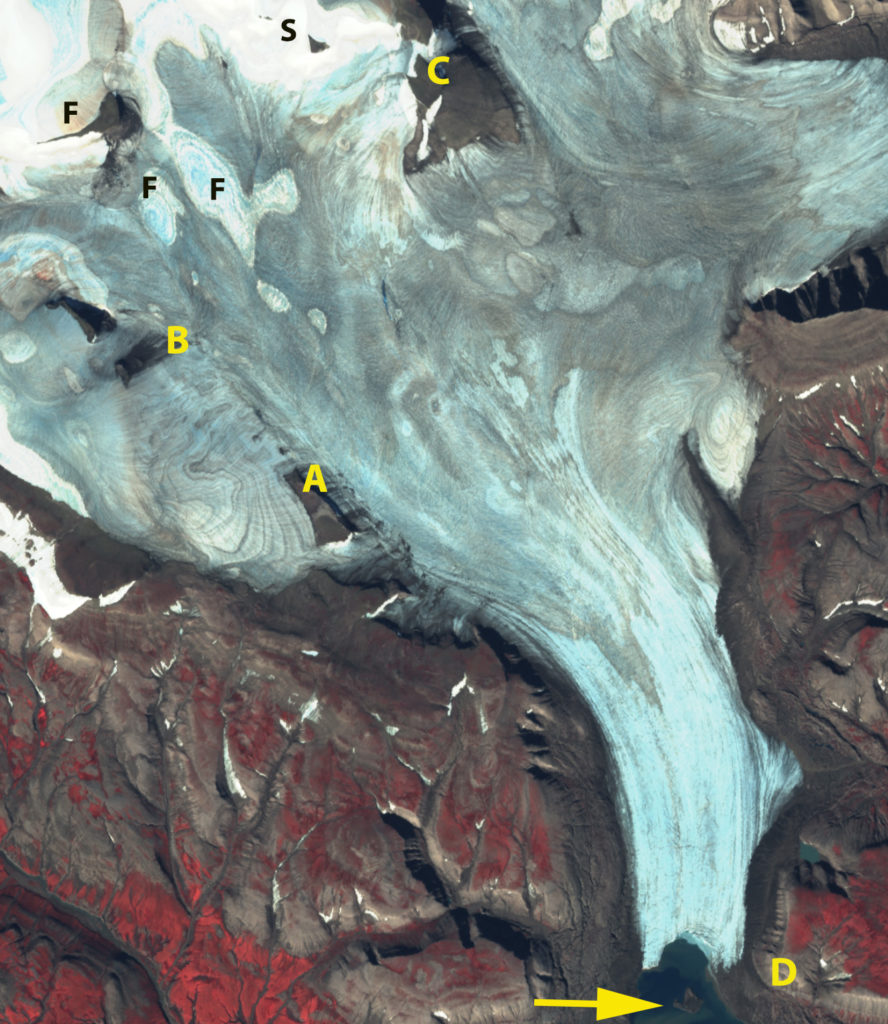

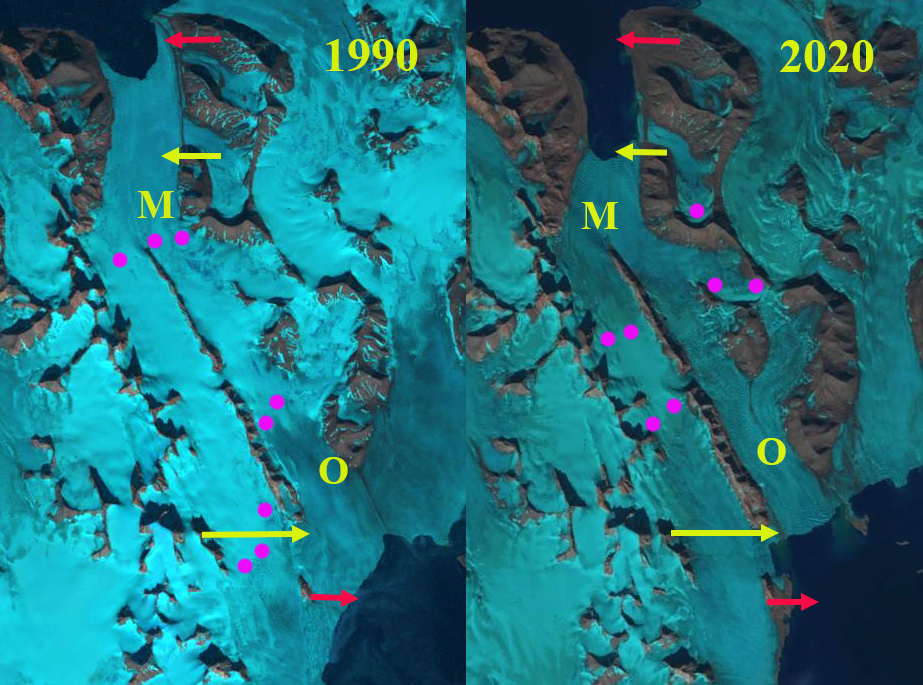

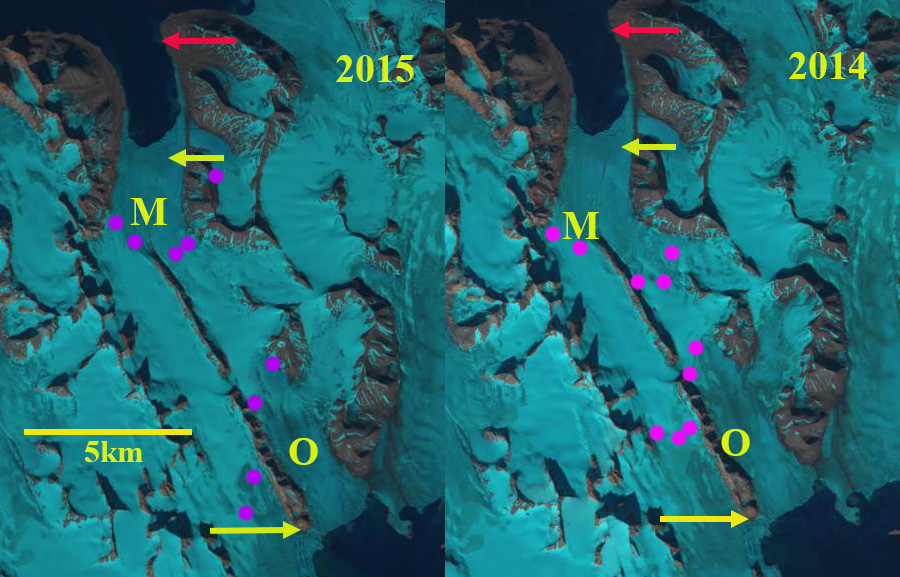

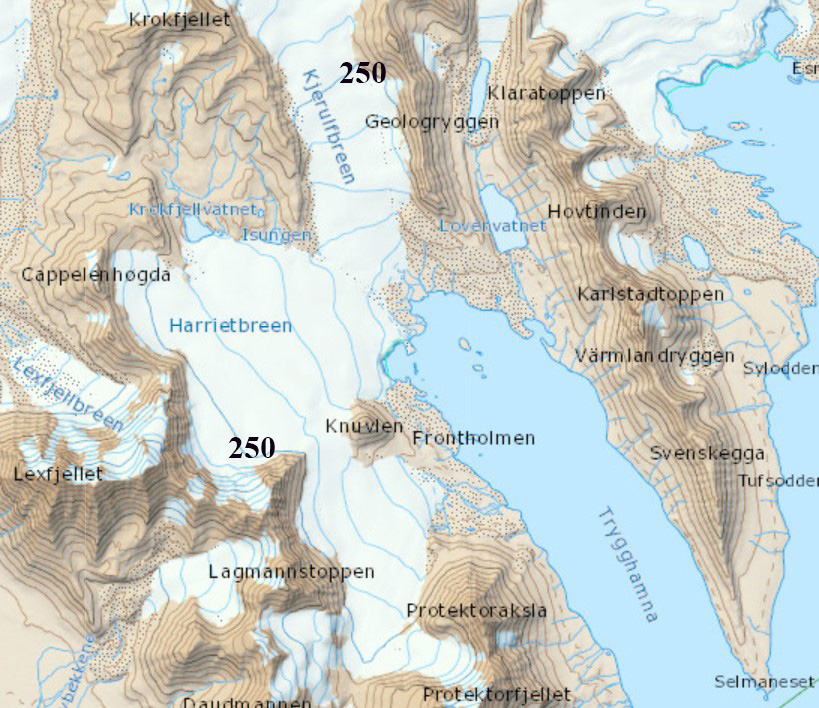

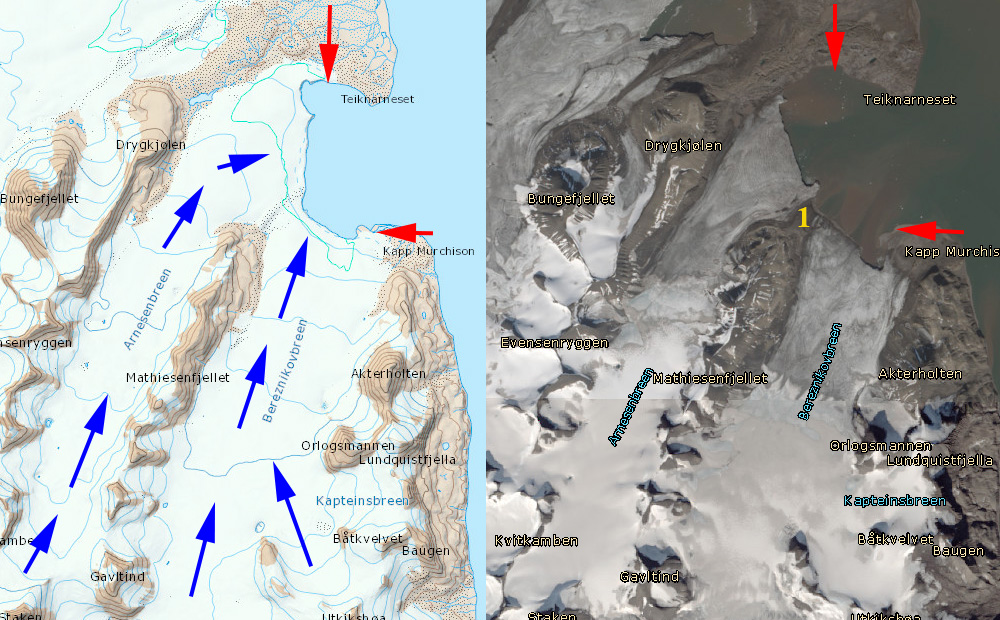

Edgeøya, Svalbard is ~40% ice covered had a number of ice caps some reaching tidewater and others in the interior (Dowdeswell and Bamber 1995). Here we focus on four inland ice caps that have there summits between 440 and 570 m. Thinning is prevalent across the Edgeøya ice caps with significant thinning even at the highest elevations, though less than at lower elevations (Morris et al, 2020). Here we examine the changes of four inland ice caps Bergfonna, Blaisen, Kvitisen and Langjokulen with Landsat imagery from 1990, 2020 and 2022. The lack of retained snow cover is evident. The annual layering is even more apparent in Sentinel imagery.

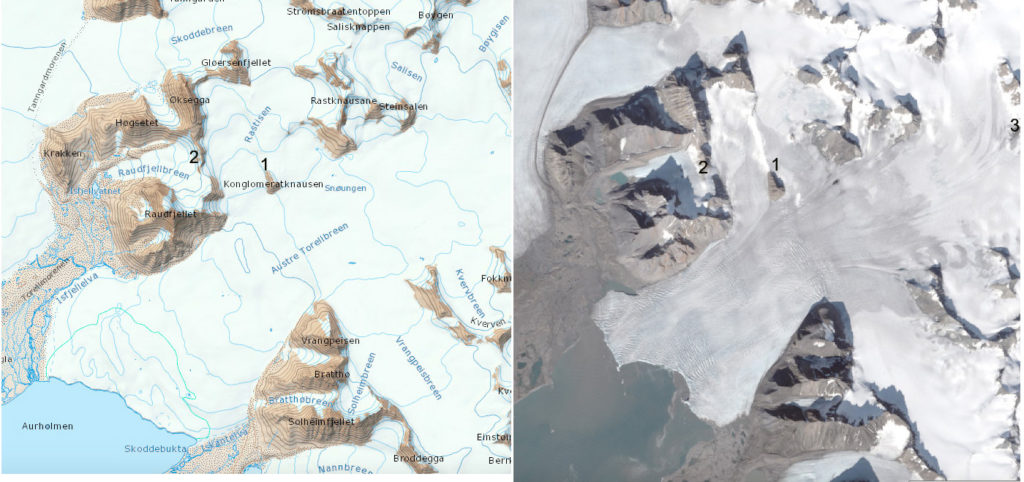

Point A- In 1990 a small glacier 0.15 km2 exists that dissapears by 2022.

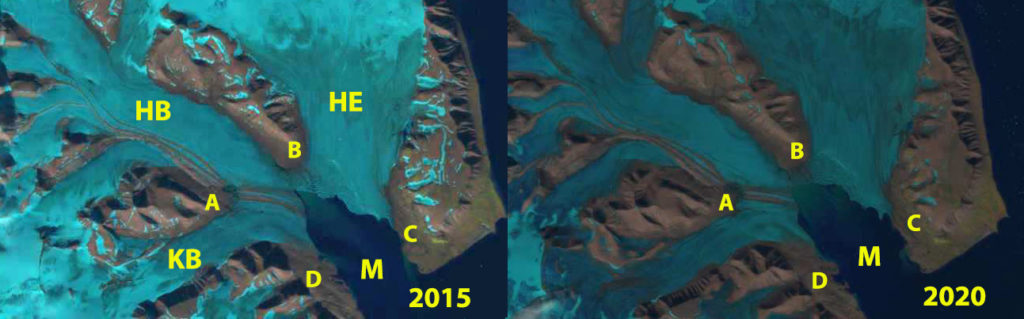

Point B and C are valleys occupied by ice from Bergfonna outlet tongues that are gone by 2022.

Point D is the valley that Bergfonna terminated in along its southern margin that is now lost most of its ice infill.

Point E and F are valleys occupied by ice from Langjokulen that have lost that ice by 2022.

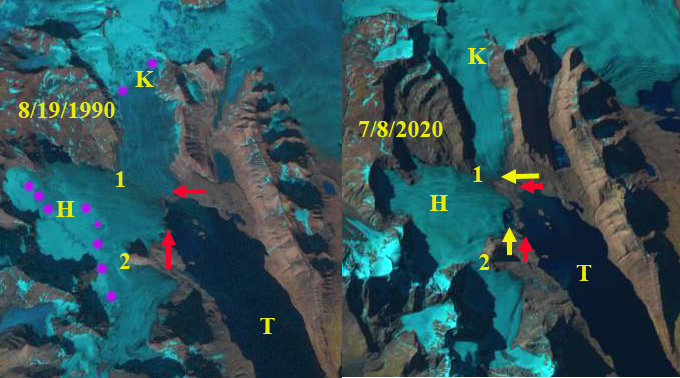

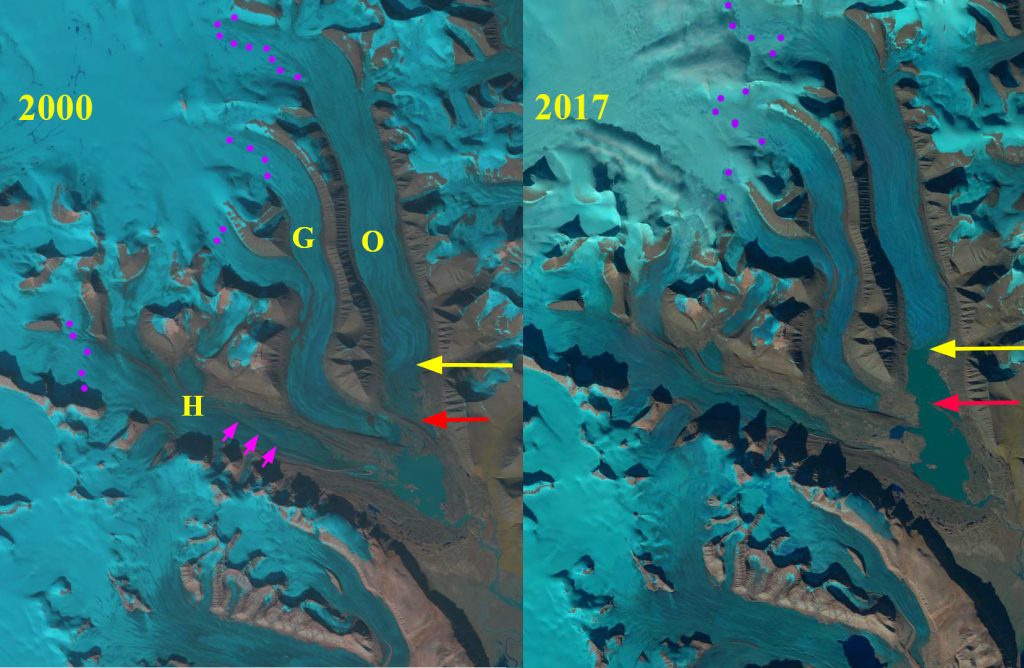

Point G and H are locations where Blaisen Ice Cap is fragmenting from 1990 to 2022.

Point I is where new bedrock is emerging as Kvitisen thins.

Point J is the location of an expanding proglacial lake now with an area of 0.3 km2 on the northwest side of Kvitisen.

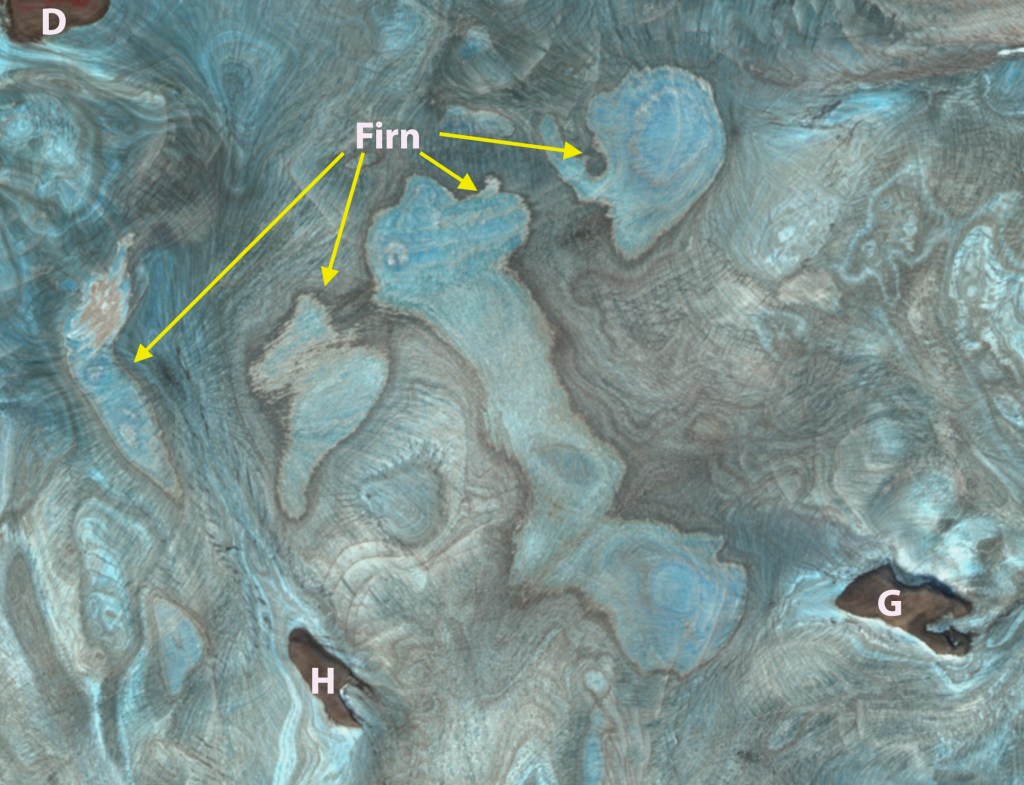

Langjokulen (La), Kvitisen (Kv), Bergfonna (Be) and Blaisen (Bl) ice caps on Edgeøya in Sentinel image from 8-20-2022 illustrating the lack of snowcover, limited firn areas and numerous annual layers. This pattern of annual layers due to glaciers being stripped of snow cover is becoming increasingly frequent. Note Andes last winter and Pacific Northwest summer 2021.

Because of the low top elevation and relatively flat slopes their ability to survive is dependent on much of meltwater generated on the higher plateau areas being refreezing within the firn instead of escaping the glacier (Noel et al 2020). In 2020 the snowcover was lost and the firn thickness diminished. In August 2022 the snowcover again has been lost and there is little evident firn that could lead to refreezing of meltwater. This will drive substantial volume loss of these ice caps in 2022. The MAR Arctic ice caps surface mass balance model illustrates the excess melt from Svalbard as over 1 m in 2022.

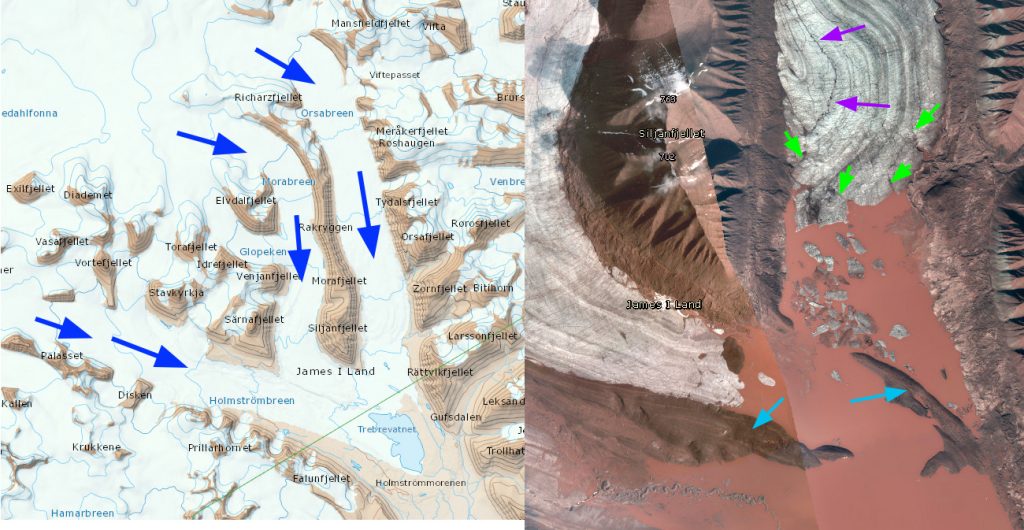

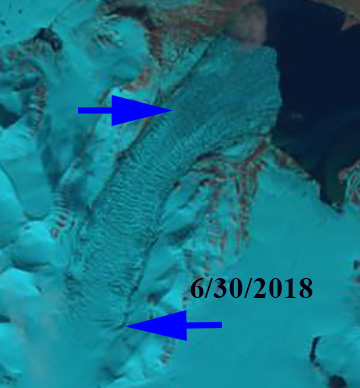

TopoSvalbard map and August 2020 Landsat image of the ice caps. This is after a recent small snow event and some drifted snow is evident, though 95% of the ice caps are snow free.