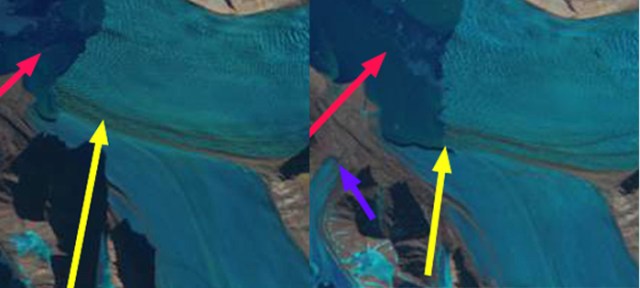

Gandbreen in 1990 and 2018 Landsat images. The red arrow indicates 1990 terminus location, yellow arrows the 2018 terminus location, and purple arrow a location where bedrock emerges.

Gandbreen is a western outlet of the Edgeøya Ice Cap, Svalbard. This is a surging glacier, that has not had an observed surge. Deltabreen a larger adjacent glacier to the south has no observed either. Strozzi et al (2017) noted that the western outlet of Edgeøya Ice Cap, Stonebreen had slowly retreating glacier front from 1971 until 2011, followed by a large increase in velocity since 2012. This is less of a true surge and potentially a change in frontal dynamics. Glaciers in Svalbard have experienced significant retreat and volume loss, including surging glaciers. Edgeøya Ice Cap has lost 18% of its area from 1936-2006 (Nuth et al 2013). ( Möller and Kohler (2018) identified this region as having had an increasing and significant mass loss from 1900-2010 driven largely by ablation increases. Here we examine the glacier changes from 1990-2018 using Landsat images.

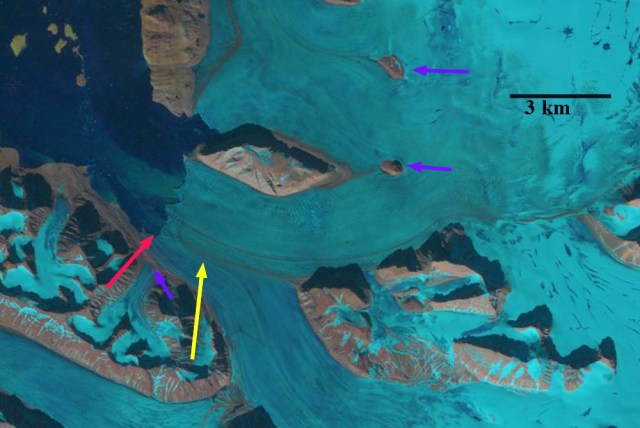

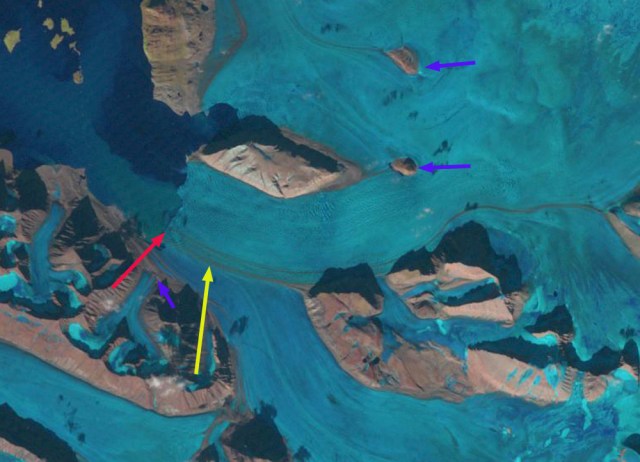

In 1990 Gandbreen’s southern margin terminated in the Gandvatnet proglacial lake, while the northern margin was grounded. The area of the lake was 3.7 square kilometer and the length of the glacier front in contact with the glacier was 3.4 km. There is not a substantial area of retained snowpack on the ice cap in 1990. By 2002 the entire margin of the glacier had retreated into the lake and the glacier front in the lake was now 7 km long. The northern half of the lake was narrow at 100-400 m wide. By 2016 further retreat and reduced the glacier front in the lake to ~5 km. A new area of bedrock had appeared, pink arrow, had appeared at an elevation of 300 m, the ice cap divide is at 400-450 m. By 2018 the southern margin of the glacier is grounded on the eastern shore of the lake. Gandvatnet has expanded to an area of 10.7 square kilometers and the margin of the glacier in the lake is 4.5 km. The terminus has retreated 1800 m on the southern margin, 1250 m in the center, and 2400 m on the north margin. There is not a substantial area of retained snowpack on the ice cap in 1990, indicating that expanded ablation has driven the retreat. The retreat of Gandbreen is less significant than at Besselbreen. Fridtjovbreen has potentially surged for the last time, has Gandbreen?

Gandbreen in 2002 Landsat image. The red arrow indicates 1990 terminus location and yellow arrows the 2018 terminus location.

Toposvalbard map of Gandbreen

Gandbreen in 2016 Landsat image. The red arrow indicates 1990 terminus location, yellow arrows the 2018 terminus location, and purple arrow a location where bedrock emerges.