Glacier Index List

Below is a list of the individual glacier posts examining our warming climates impact on each glacier. This represents the first 2.5 years of posts, 166 total posts, 152 different glaciers. I have worked directly on 39. The others are prompted by fine research that I had come across, cited in each post or inquiries from readers and other scientists. I then look at additional often more recent imagery to expand on that research. The imagery comes either from MODIS, Landsat, Geoeye or Google Earth.

North America

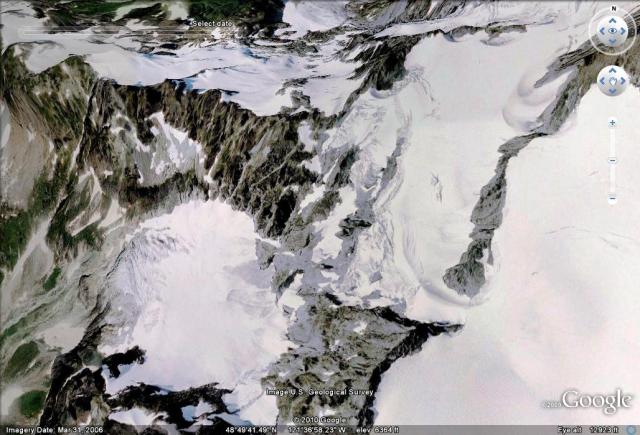

Columbia Glacier, Washington

Lyman Glacier, Washington

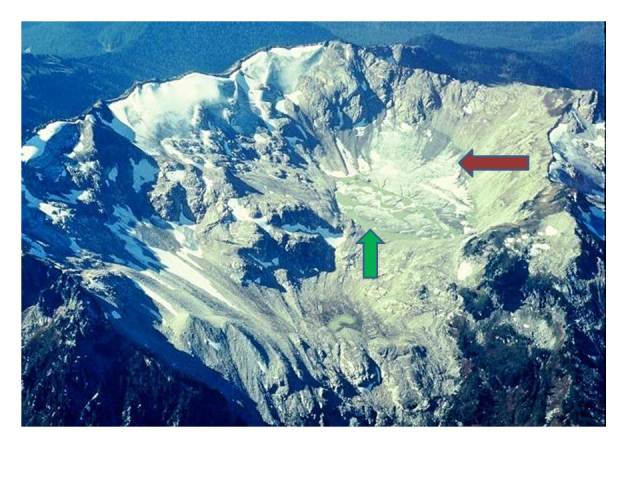

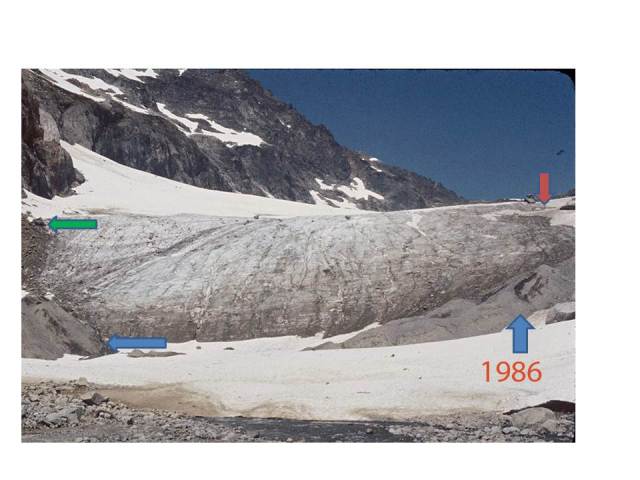

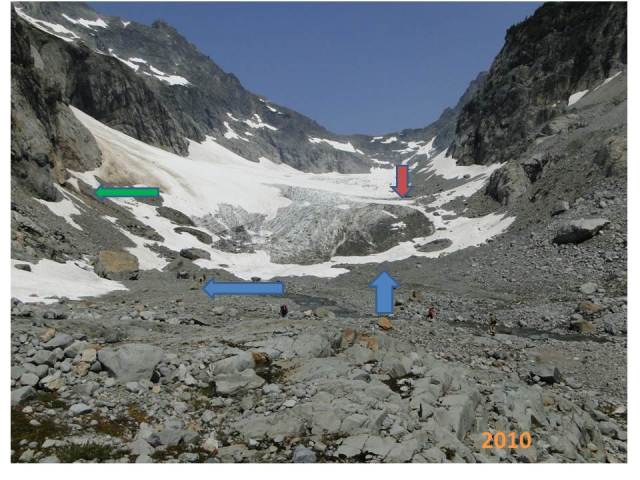

Boulder Glacier, Washington

Ptarmigan Ridge Glacier, Washington

Anderson Glacier, Washington

Milk Lake Glacier, Washington

Paradise Glacier, Washington

Easton Glacier, Washington

Redoubt Glacier, Washington

Honeycomb Glacier, Washington

Vista Glacier, Washington

Rainbow Glacier, Washington

Daniels Glacier, Washington

Colonial Glacier, Washington

Quien Sabe Glacier, Washington

Mazama Glacier

Fairchild Glacier, Washington

White Glacier, Washington

Banded Glacier, Washington

Borealis Glacier, Washington

Hinman Glacier, Washington

Lower Curtis Glacier

McAllister Glacier, Washington

Lewis Glacier, Washington

Kennedy Glacier, Washington

Bridge Glacier, British Columbia

Washmawapta Glacier, British Columbia

Bubagoo Glacier, British Columbia

Hector Glacier, Alberta

Helm Glacier, British Columbia

Melbern Glacier

Warren Glacier, British Columbia

Castle Creek Glacier, British Columbia

Hoboe Glacier, British Columbia

Tulsequah Glacier, British Columbia

Decker and Spearhead Glacier, British Columbia

Columbia Glacier, British Columbia

Freshfield Glacier, British Columbia

Apex Glacier, British Columbia

Devon Ice Cap, Nunavut

Penny ice Cap, Nunavut

Minor Glacier, Wyoming

Grasshopper Glacier, Wyoming

Fremont Glacier, Wyoming

Grasshopper Glacier, Montana

Harrison Glacier, Montana

Sperry Glacier, Montana

Hopper Glacier, Montana

Old Sun Glacier, Montana

Yakutat Glacier, Alaska

Grand Plateau Glacier, Alaska

Eagle Glacier, Alaska

Gilkey Glacier , Alaska

Gilkey Glacier ogives, Alaska

Lemon Creek Glacier, Alaska

Taku Glacier, Alaska

Bear Lake Glacier, Alaska

Chickamin Glacier, Alaska

Okpilak Glacier, Alaska

Sawyer Glacier, Alaska

Antler Glacier, Alaska

Field Glacier

East Taklanika Glacier, Alaska

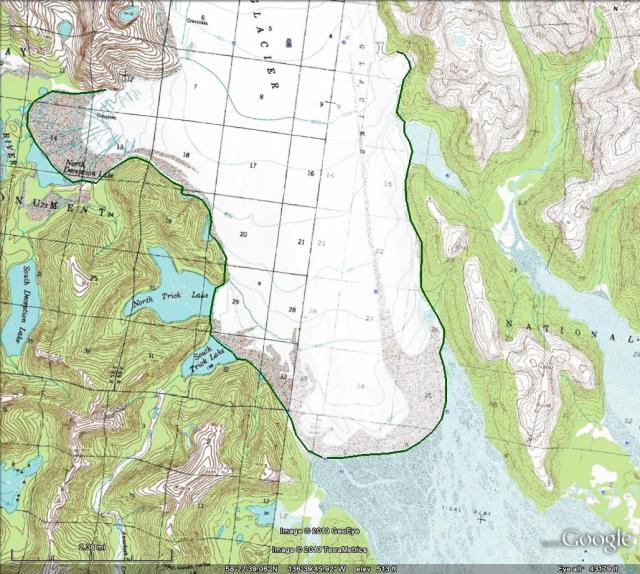

Brady Glacier, Alaska

Brady Glacier Retreat lake expansion 2004-2010

Thiel Glacier, Alaska

New Zealand

Tasman Glacier

Murchison Glacier

Donne Glacier

Mueller Glacier, NZ

Gunn Glacier, NZ

Africa

Rwenzori Glaciers

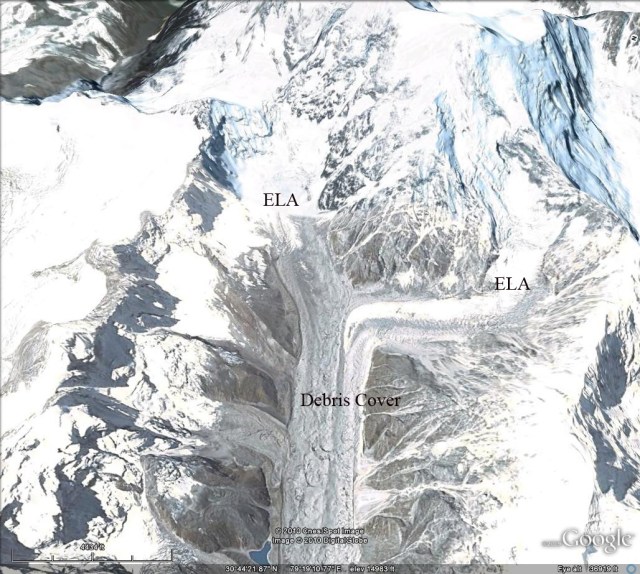

Himalaya

Zemu Glacier, Sikkim

Theri Kang Glacier, Bhutan

Zemestan Glacier, Afghanistan

Khumbu Glacier, Nepal

Imja Glacier, Nepal

Gangotri Glacier, India

Milam Glacier, India

Satopanth Glacier, India

Kali Gandaki Headwaters, Nepal

Menlung Glacier, Tibet

Boshula Glaciers, Tibet

Urumquihe Glacier, Tibet

Sara Umaga Glacier, India

Dzhungharia Alatau, Kazakhstan

Petrov Glacier,Kyrgyzstan

Hailuogou Glacier, China

Europe

Mer de Glace, France

Dargentiere Glacier, France

Grand Motte and Pramort Glacier Tignes Ski area, France

Saint Sorlin, France

Sommelier Glacier

Obeeraar Glacier, Austria

Ochsentaler Glacier, Austria

Pitzal Glacier, Austria

Dosde Glacier, Italy

Maladeta Glacier, Spain

Presena Glacier, Italy

Triftgletscher, Switzerland

Rotmoosferner, Austria

Stubai Glacier, Austria

Ried Glacier, Switzerland

Cavagnoli Glacier, Switzerland

Chuebodengletscher and Ghiacciaio-del-Pizzo-Rotondo

Forni Glacier, Italy

Peridido Glacier, Spain

Engabreen, Norway

Midtdalsbreen, Norway

TungnaarJokull, Iceland

Gigjokull, Iceland

Skeidararjokull, Iceland

Kotlujokull, Iceland

Lednik Fytnargin, Russia

Rembesdalsskaka, Norway

Hansbreen, Svalbard

Nannbreen, Svalbard

Hornbreen and Hambergbreen, Svalbard

Roze and Sredniy Glacier, Novaya Zemyla

Irik Glacier, Mount Elbrus, Russia

Greenland

Mittivakkat Glacier

Ryder Glacier

Humboldt Glacier

Petermann Glacier

Kuussuup Sermia

Jakobshavn Isbrae

Umiamako Glacier

Kong Oscar, Glacier

Upernavik Glacier

Sortebrae Glacier, Greenland

South America

Colonia Glacier, Chile

Artesonraju Glacier, Peru

Nef Glacier, Chile

Tyndall Glacier, Chile

Zongo Glacier, Bolivia

Llaca Glacier, Peru

Seco Glacier, Argentina

Onelli Glacier, Argentina

Quelccaya Ice Cap, Peru

Glacier Gualas, Chile

Antarctica and Circum Antarctic Islands

Pine Island Glacier

Fleming Glacier

Hariot Glacier

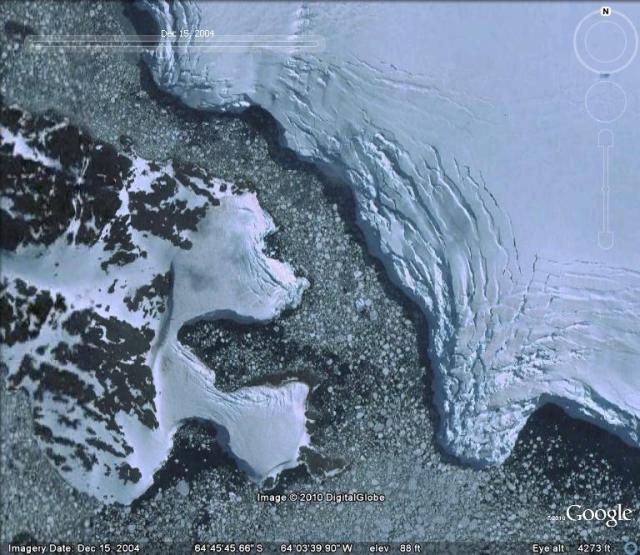

Amsler Island

Stephenson Glacier, Heard Island

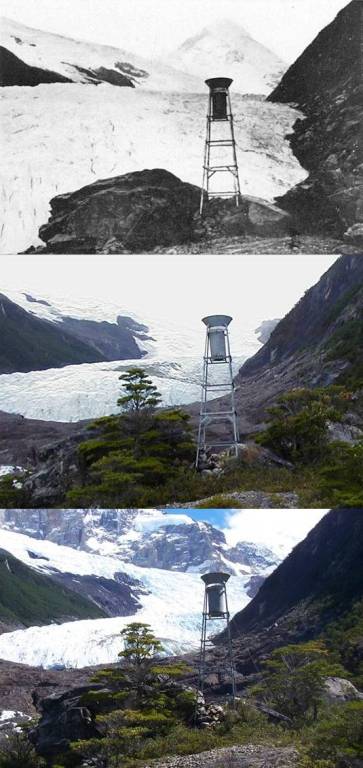

Neumayer, South Georgia

Ampere, Kerguelen

Nordenskjold Coast, Antarctic Peninsula

Prospect Glacier, Antarctic Peninsula

Ross Hindle Glacier, South Georgia

Vega Island Ice Cap

North Cascade Glacier Climate Project Reports

Forecasting Glacier Survival

North Cascade Glacier Mass Balance 2010

Columbia Glacier Annual Time Lapse

North Cascade Glacier Climate Project 2009 field season

28th Field Season Schedule of the North Cascade Glacier Climate Project

North Cascade Glacier Climate Project 2011 Field Season

BAMS 2010

2011 Glacier mass balance North Cascades and Juneau Icefield

Taku Glacier TSL Paper