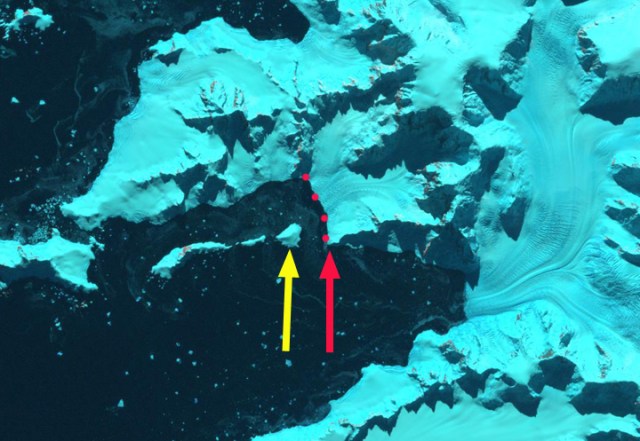

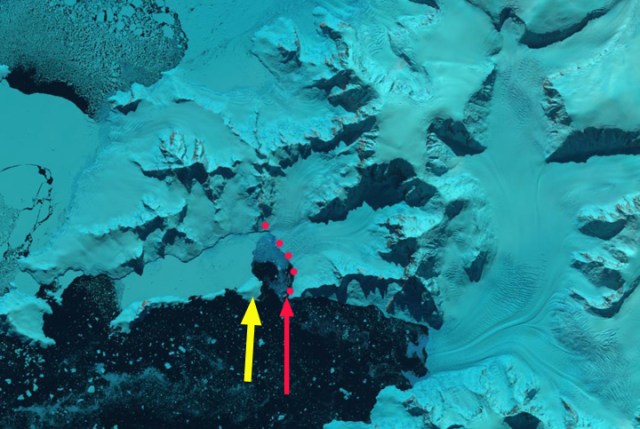

Cape Longing, Antarctica in 2001 and 2018 Landsat images. Point A-G are at specific locations. Yellow dots mark the margin of the glacier connecting the Cape to the main Antarctic Peninsula.

Cape Longing is on the Antarctic Peninsula between Larsen Inlet and Prince Gustav Channel. Larsen Inlet along the south shore of Cape Longing was covered by the Larsen A Ice Shelf until its collapse in 1995. The Prince Gustav Ice Shelf extended across the channel from the north shore of Cape Longing until the 1980’s. This 1600 square kilometer ice shelf disintegrated in the mid-1990’s and was gone by 1995 (Cook and Vaughan, 2010). Here we examine changes in the glacier connecting Cape Longing to the Antarctic Peninsula from 2000 to 2018 using Landsat imagery.

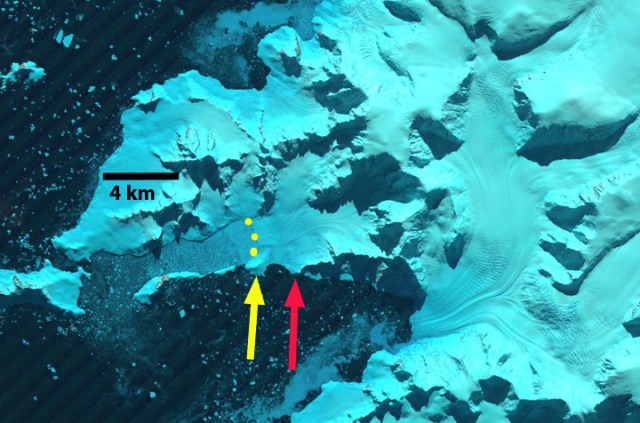

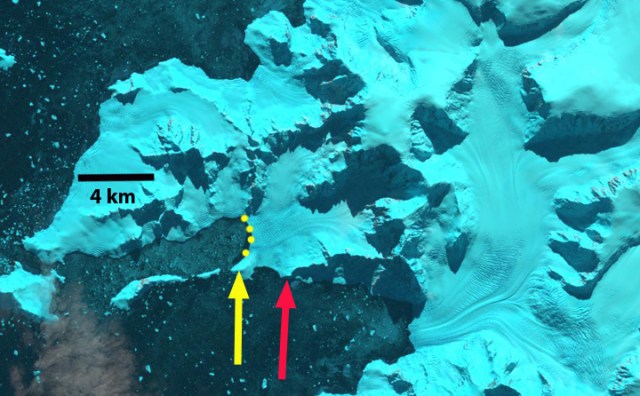

In 2000 the glacier connecting Cape Longing with the main peninsula extended along a front from Point F to Point E. Northeast of Point G there is an area of rifted ice indicative of ice that had been grounded going afloat. On the southern margin the ice front extends southwest from Point A. The glacier from the northern to the southern margin is ~9 km across. In 2001 the southern margin has not changed, but the northern margin indicates an expanded ice melange between the active glacier and the ice front, making the exact terminus difficult to pinpoint. By 2017 the northern ice margin has retreated to a line between Point B and Point G. The southern margin extends west from Point A. In 2018 it is 3.5 km from the northern to southern margin, more than 60% of this glacier connection to Cape Longing has been lost since 2000. This connection appears to have a below sea level bed though the glacier is grounded. This grounding should lead to a slower retreat. The ice shelf/glacier retreat at Cape Longing is significant though much less than the more dynamic nearby Sjogren Glacier.

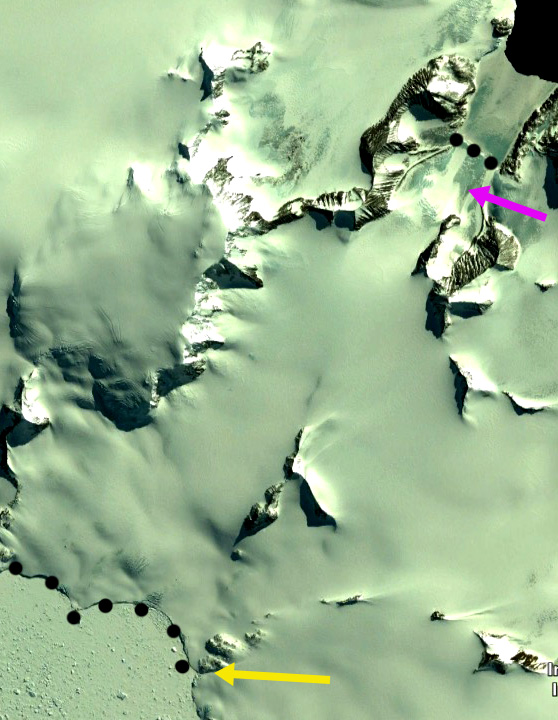

View of Cape Longing in REMA Antarctic Explorer, which is the 2000 Landsat image.

Cape Longing, Antarctica in 2000 and 2017 Landsat images. Point A-G are at specific locations. Yellow dots mark the margin of the glacier connecting the Cape to the main Antarctic Peninsula.