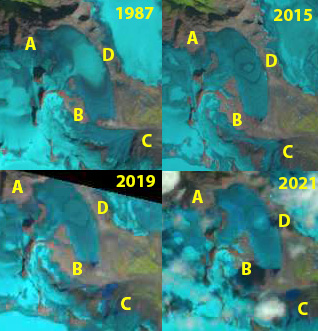

Todd Icefield in 1987 and 2020 Landsat images illustrating retreat and separation. Red arrows indicate 1987 terminus location, Point A indicates location where the glacier has separated. Point B and C are locations of expanding bedrock high on the icefield. Point D is further glacier separation.

Todd Icefield is an icefield 30 km northeast of Stewart BC at the head of Portland Canal, with Todd Glacier being the main outlet glacier draining north to Point A and Erickson Glacier draining south near Point B. Glaciers of this icefield retreated and downwasted significantly from 1974-1997, with retreat rates of 9-76 m/year (Jackson et al 2008). Menounos et al (2019) indicate mass loss averaging -0.5 m/year from 1985-2018 in this region.

In 1987 Todd Glacier terminates in a small proglacial lake 1 km beyond a glacier junction at Point A. At Point B and C there are small bedrock outcrops. It is also worth noting that you could hike from the end of Todd Glacier on the northside across the icefield divide to the Erickson Glacier on the south side without crossing any snowcover. By 1997 Todd Glacier has retreated from the now 0.5 km long proglacial lake, with the two glacier tributaries joining just before the terminus. Again the snowline is above the Todd Icefield divide.

In 2013, 2014, 2015, 2018 and 2019 the snowline again rose above the icefield divide, leading to continued thinning even at the divide leading to increased bedrock exposure at Point B and C in 2018-2021. By 2020 Todd Glacier has retreated m since 1987 and separated from the main tributary at Point A. In 2018-2021 it is evident that Erickson Glacier is terminating in two new expanding proglacial lakes (0.2 km2) that may merge, and Todd Glacier is also now terminating in a new proglacial lake.

Retreat of Todd Glacier has been 2.4 km from 1987-2021, which is 30-40% of it entire length. The retreat is in line with that observed at nearby Bromley Glacier and Chickamin Glacier.

Todd Icefield in 1997 and 2021 Landsat images illustrating retreat and separation. Red arrows indicate 1987 terminus location, Point A indicates location where the glacier has separated. Point B and C are locations of expanding bedrock high on the icefield. Point D is further glacier separation.

Todd Icefield in 2018 and 2019 Sentinel images, note the dirty ice extends across the icefield divide in both years, yellow arrows indicate proglacial lakes developing.