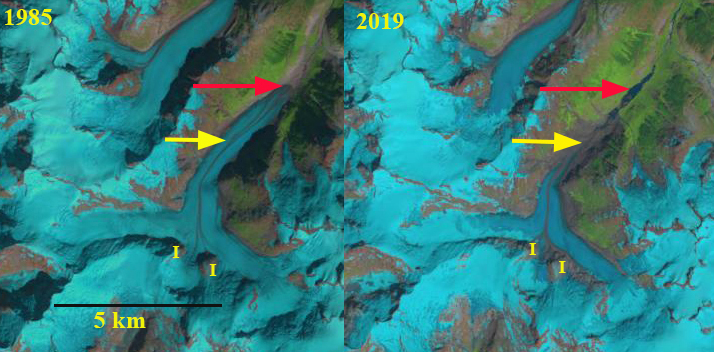

Falcon Glacier in 1985 and 2019 Landsat images indicating the 2000 m retreat. Red arrow is 1985 terminus location, yellow arrow the 2019 terminus location. I=icefall locations joining the glacier.

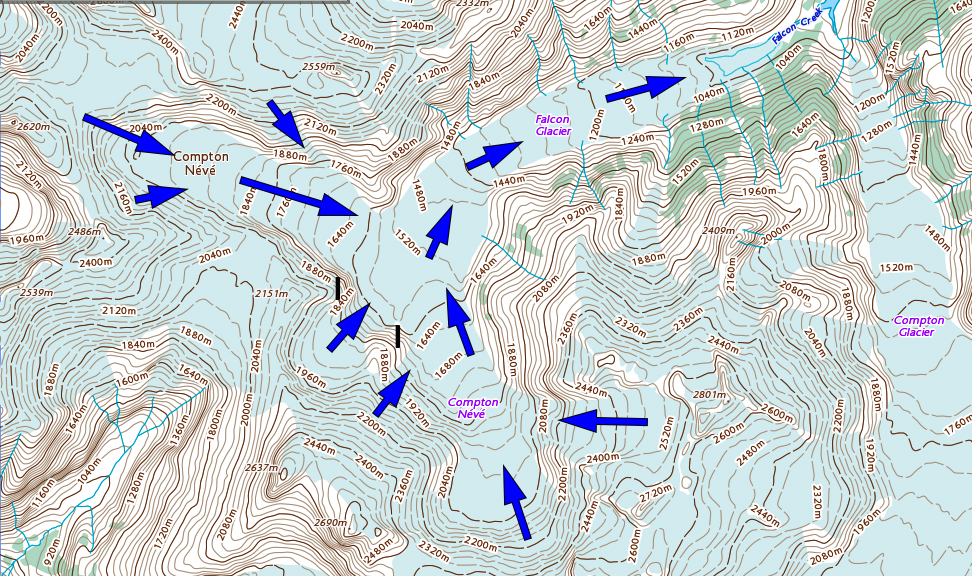

Falcon Glacier in southwest British Columbia drains east from the Compton Neve into the Bishop River, which then joins the Southgate River. The Southgate River is one of three major watersheds emptying into the head of Bute Inlet. The Southgate River is known for the large runs of Chum Salmon. The area was the focus of a proposed Bute Inlet hydropower, that at present is no longer being pursued. The region has experienced large negative mass balances 2000-2018 (Menounos et al 2018), that is driven retreat of many glaciers in the immediate area such as Bishop Glacier and Klippi Glacier. Here we examined Landsat images from 1985 to 2019 to determine the response to climate change of Falcon Glacier.

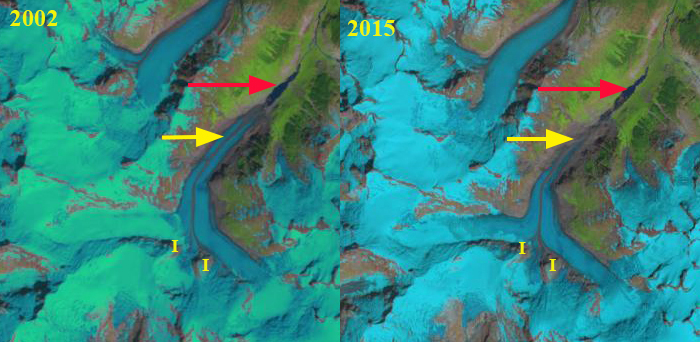

In 1985 Falcon Glacier terminated at 980 m and was over 10 km long (red arrow). There were two icefalls (I) feeding the glacier along with the two principal tributaries. By 2002 the glacier had retreated 800 m, with narrow ponding in front of the terminus. The two icefalls were still active and the medial moraine extending to the terminus had increased prominence. By 2015 the glacier had retreated another 800 m and the two icefalls are barely connected to the main glacier. The snowline is higher in 2015 at 1850 m. By 2019 Falcon Glacier had retreated 2000 m, losing 20% of its length since 1985. The eastern icefall no longer rejoins the main glacier. The western icefall is barely connected. The snowline in early August 2019 is already at 1850 m indicating a limited accumulation area again. The high snowlines and continued expansion of bedrock areas even at 2000 m indicates the glacier will continue its rapid retreat.

Falcon Glacier in 2002 and 2015 Landsat images indicating the 2000 m retreat. Red arrow is 1985 terminus location, yellow arrow the 2019 terminus location. I=icefall locations joining the glacier.

Map of Falcon Glacier indicating flow direction and icefalls (I).