Icemantle Glacier in Landsat images from 2000-2022 illustrating the retreat exposing a new lake (Point A) and separation at Point D. Also the lack of snowcover in 2009, 2015 and 2022 indicative of mass balance loss that drives retreat.

Icemantle Glacier is on the north side of Greenmantle Peak just north of Snowcap Lake in the Lilloet River Basin of southwest British Columbia. Here we focus on the retreat and thinning of the glacier this century using Landsat imagery and then lack of snowcover extending into mid-October in 2022 using Sentinel images.

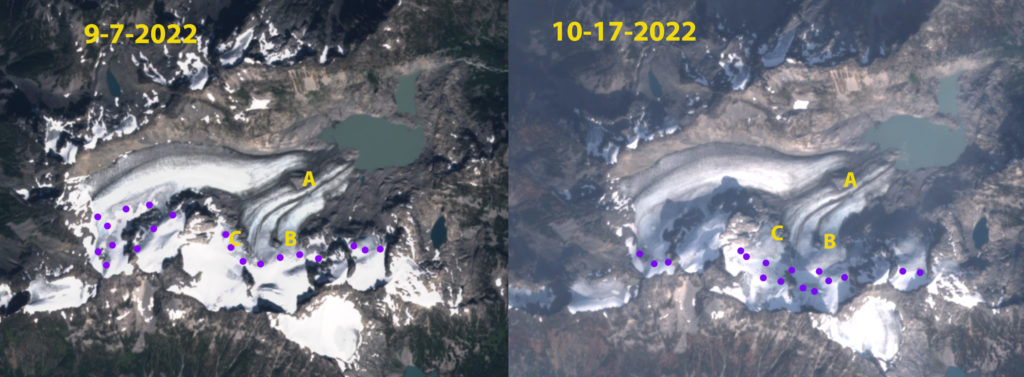

In 2000 the glacier extended across the basin where the new lake would soon form. The Landsat image from July 31, indicates near complete snowcover at the halfway point of themelt season. By 2009 a frining lake is evident between Point A and B. Snowcover is limited to the upper reaches above 2100 m. By 2015 the lake is evident and has numerous icebergs. Below Point B a bedrock knob is just emerging. At Point D the tributary is completing separation. In 2022 the glacier is receding from the lake basin. The bedrock knob below Point B in Landsat image and at Point A in Sentinel image has emerged. The snowline rises from 2000-2050 m in early September to 2100-2150 m by mid-October. At this point the glacier should have new snowcover, and not still be actively melting.

The lake has an area of 0.3 km2 and will not expand much more. The glacier has retreated 600 m this century and given the lack of consistent retained snowcover cannot survive current climate (Pelto, 2010). The thinning of this glacier has led to expansion and emergence of bedrock knobs at Point A-C. The retreat of this glacier fits the local pattern seen at nearby Stave Glacier. The surface darkening due to less snowcover and snowcover that has more light absorbing particles at its surfaces enhances melt. Forest fires do result in some darkening of the glacier surface (Orlove, 2020).

Icemantle Glacier in early September, when snow melt is usually largely offset by occassional new snowfall, and mid-October 2022 after a month of continue ablation reduced snowcover significantly. Notice the expansion and emergence of bedrock at Point A-C.