2022 North Cascade Glacier Climate Project Field Team

Science Director: Mauri S. Pelto, mspelto@nichols.edu

Art Director: Jill Pelto, pelto.jill@gmail.com

For the 39th consecutive summer we were in the field to measure and communicate the impact of climate change on North Cascade glaciers. We completed detailed measurements on 10 glaciers, three of which are part of the World Glacier Monitoring Service reference glacier network (42 glaciers globally), which have 30+ consecutive years of mass balance observations. NCGCP was founded in 1983 to identify and communicate the response of North Cascade glaciers to regional climate change. We are a fieldwork-based project with a focus on measuring changes in mass balance, glacier runoff, and terminus behavior. The project has an interdisciplinary scope — collaborating with a range of natural scientists, artists, journalists, and conservationists.

This winter snowpack remained below average until a late season surge from April into May. Snowpack was 90% of the mean (1977-2021) on April 1% and 110% of the mean on May 10. The month of May and June had below normal temperatures leading to an above average glacier snow cover as June ended. July and August were exceptionally warm at Heather Meadows (4200 feet) average July and August maximum temperature is 19.2 C, this year 20 days reached or exceeded 5 C above this temperature in July and August 2022. At Stevens Pass (4000 feet) average July and August maximum temperature is 21.4 C, this year 24 days reached or exceeded 5 C above the temperature in July and August 2022. The average July-August temperature at the Stevens Pass and Lyman Lake sites was the highest since records began in 1990.

The result is that glacier snowcover rapidly melted during the July-August period, which is resulting in significant mass losses for North Cascade glaciers that continue to thin, retreat and lose volume. The climate stress is evident on the glaciers, but also in the alpine vegetation and alpine aquatic ecosystems.

Field team backpacking around Blanca Lake at our first field site.

Columbia Glacier with the 1984 terminus position, note the glacier profile now descends from west side (left) to east side (right) of the glacier. The glacier has retreated 270 m since 1984. Note steep tongue extending across entire cirque valley in 1988 lower image.

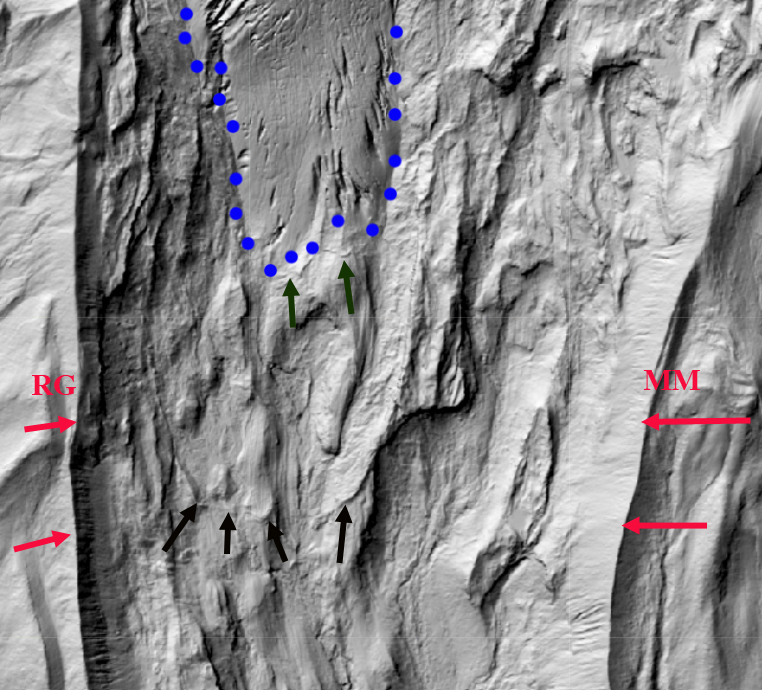

Columbia Glacier indicating the avalanche fans that now provide most of the accumulation to the glacier at the blue arrows. The yellow arrows indicate avalanche slopes that are no longer key feeders resulting in marginal thinning and recession. These locations or reduced avalanching have resulted from the source area slopes having lost their perennial snow and ice, which must be filled each winter before a slide can occur. Snowpack in the avalanche fans exceeds 3 m, while outside of the avalanche fans averaged 1.8 m on Aug. 1-2, 2022.

Jill Sketching Blanca Lake and Troublesome Creek draining from Columbia Glacier.

Braided stream issuing from the the rapidly retreating and thinning Sholes Glacier on the north flank of Mount Baker. Retreat since 2015 has been 90 m, with 225 m since 1984.

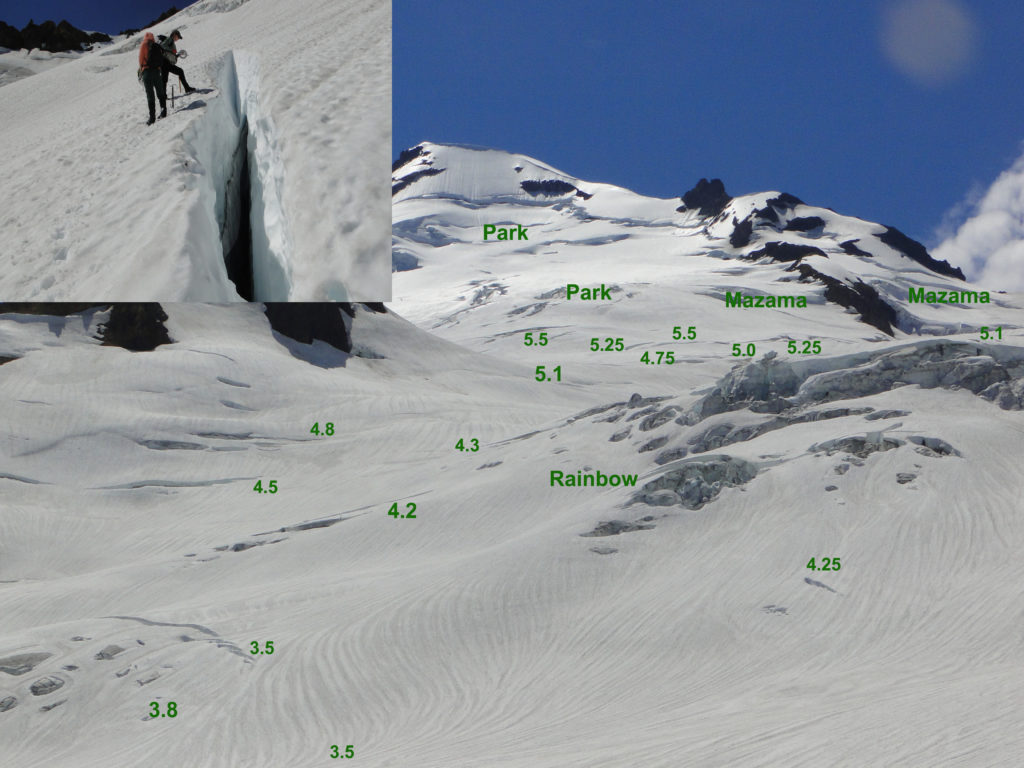

Snow depth measurements in meters on Rainbow Glacier using crevasse stratigraphy, adjacent Park and Mazama Glacier drain the upper part of Mount Baker. Average depth at 2000 m was 5.25 m, 3.15 m water equivalent. The terminus of the glacier continues to retreat rapidly, but was buried by avalanche debris at the time of our survey in 2022.

Alia Khan’s Western Washington University team assessing a red algae zone on Rainbow Glacier, we led them through the icefall to this location, where they sample impurities on the glacier surface and relate that to remote sensing products.

Jill’s sketch of Rainbow Glacier and Mount Baker from trail above Lake Ann.

Lower Curtis Glacier indicating recession since 1985. The glacier has thinned considerably in the lower section since the 2003 image below.

Navigating through the icefall region on Lower Curtis Glacier where we are mapping snow pack depth and crevasse depth.

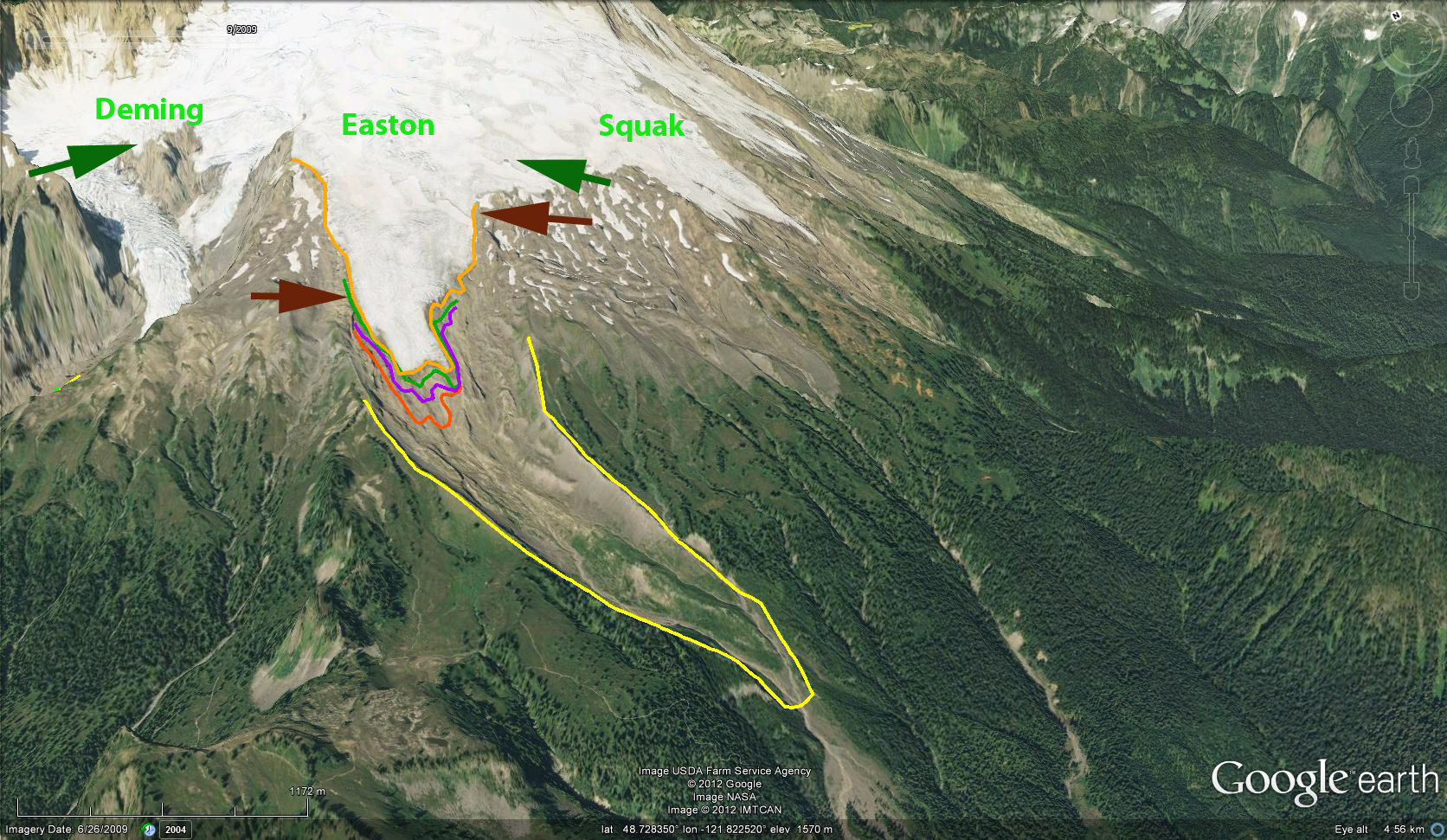

Deglaciated terrain since 1990 below Easton Glacier. We mapped this at 0.18 square kilometers in 2022.

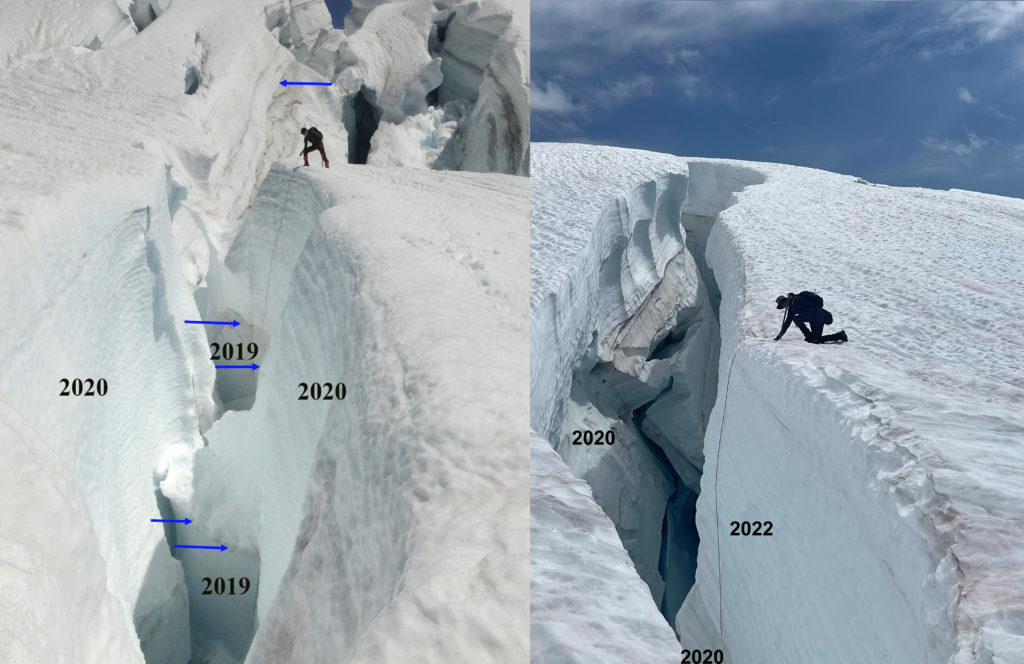

We have observed crevasse depths for a decade and have seen both their number and depth decline in icefalls on Easton and Lower Curtis Glacier due to glacier thinning and reduced velocity. Deepest crevasses are at the top of the convex slope change, 25-30 m deep.

Claire Giordano painting Easton Glacier crevasse ‘blues’ at top of lowest icefall.

Ascending into Easton Icefall with five annual layers exposed on serac.

Snow depth assessment in specific crevasse at 2500 on Easton Glacier. No snow was retained here in 2021. Avergage depth in 2020 in this region 5.5 m, 4.75 m in 2022.

Easton Glacier has retreated 470 m from 1990-2022. Above is 2022 and below is 2003 image.

Ice Worm Glacier on Mount Daniel was fully snowcovered. We completed a grid of 72 snow depth measurements with a mean of 2.1 m in depth. The glacier continues to recede faster on its upper margin than at the terminus.

Descending onto Lynch Glacier, which had an accumulation area ratio of 83% in mid-August. Average snow depth 2.5 m.

Probing snow depth and surveying blue ice margin on Lynch Glacier.

Daniel Glacier was fully snowcovered in mid-August. Consistent snow depths of 1.8-2.5 m.

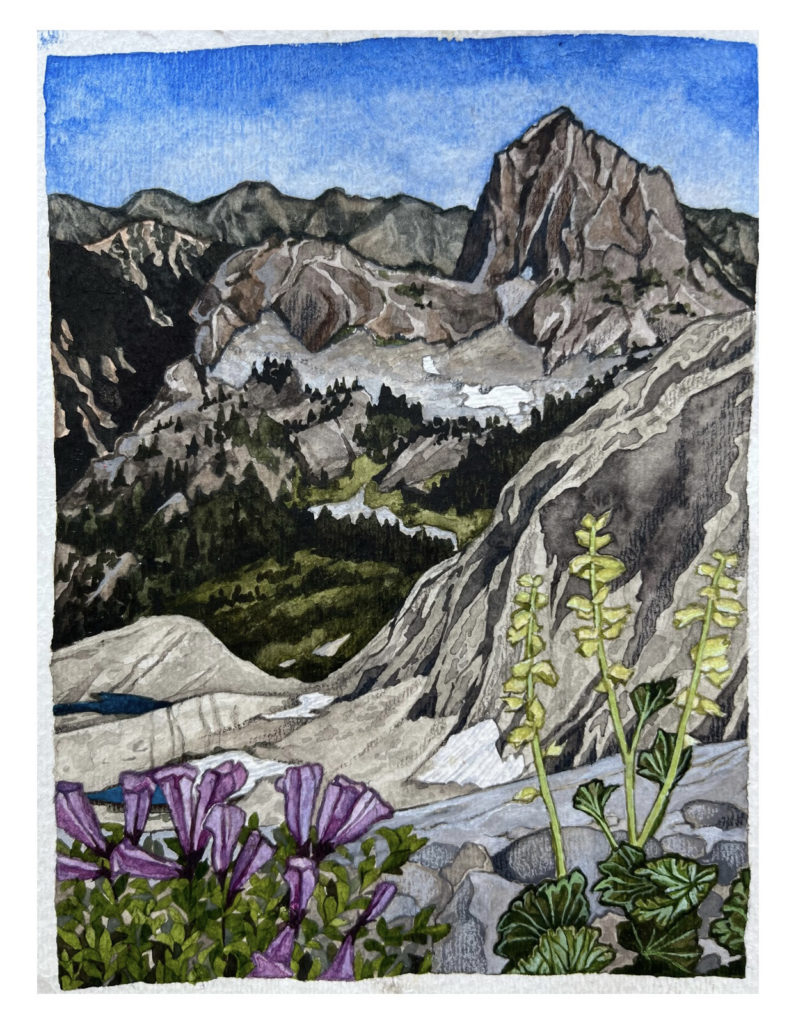

Jill’s field watercolor and colored pencil. This piece was done below the small Iceworm Glacier, on Mt. Daniel. It looks out towards the prominent Cathedral rock and Alpine Lakes Wilderness. Jill really enjoyed making this piece — to start she sketched the landscape, and then temporarily moved in front of the purple penstemon and the pale elmira flowers to capture them in the foreground. A while after she began painting, the wind dropped, and the mosquitoes arrived in force. Jill had to stop painting for the evening and went back to camp. Because Jill then finished at home, it was fun to add some more detail to this piece.

In the vicinity of Peggy’s Pond near our Mount Daniel base camp are a dozen shallow ponds, 10-20 cm are average that typically endure through the hatch of tadpoles in late August or early September. The primary inhabitants are frogs (Rana Cascadea) and their tadpoles. In 2022 despite a wet spring and early summer that had the ponds brimming with water, right above, tadpoles were observed, where typically there are several hundred, and the frog numbers were ~50% of usual. This followed the dried beds of these ponds in 2021, at left. Maybe this is in part why mosquitoes were swarming here.

In 2021 below Easton Glacier we noted a number of alpine plants that had emerged just before or during the record June heat wave, had been dessicated/cooked by the heat in this are of relatively barren volcanic rock. Most notably lupine. This year in the same region we noted that ~30% of the lupine had failed to develop by August 2022, despite a cool wet spring. In contrast the evergreen alpine plants in the same area penstemon, saxifrage, pink and white heather, and partridge-foot all were fine.

Easton Glacier extends from the terminus at 5600 feet to the slopes near Sherman Crater at 9000 feet. Each summer since 1990 NCGCP has measured the mass balance of this glacier. View

Easton Glacier extends from the terminus at 5600 feet to the slopes near Sherman Crater at 9000 feet. Each summer since 1990 NCGCP has measured the mass balance of this glacier. View