Recipe for Mountain Glacier Formation:

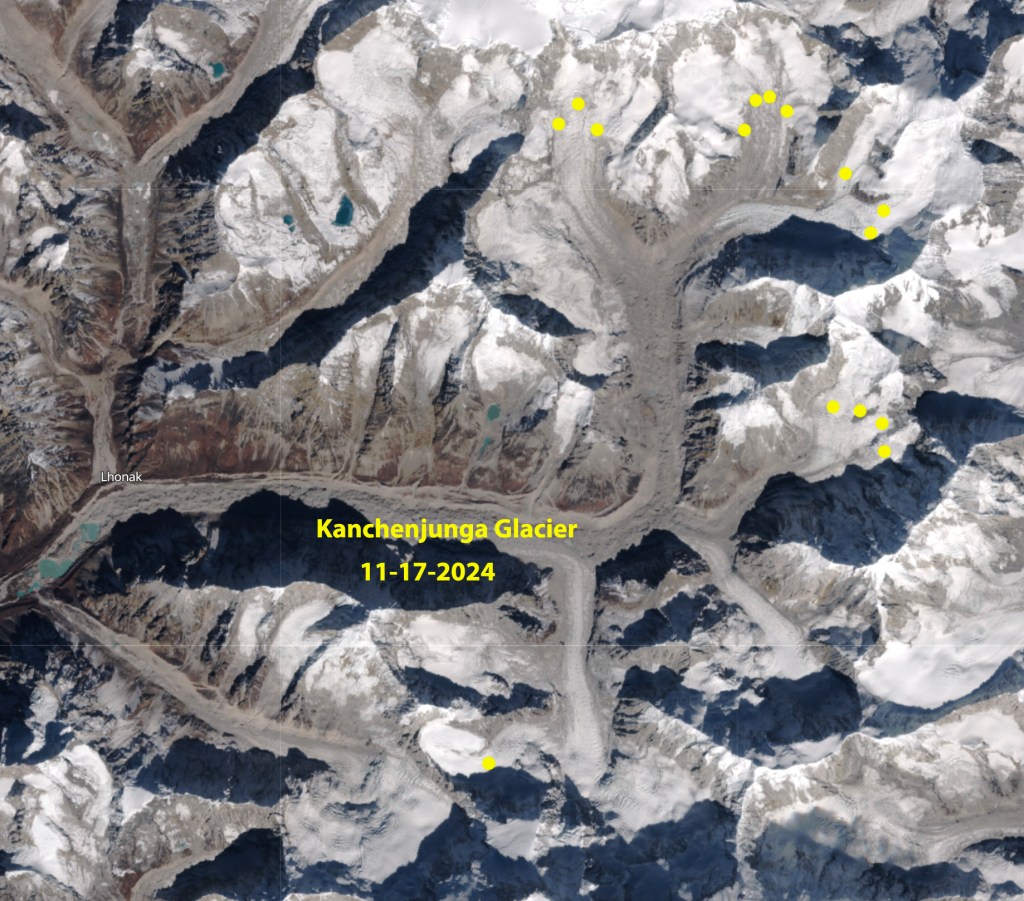

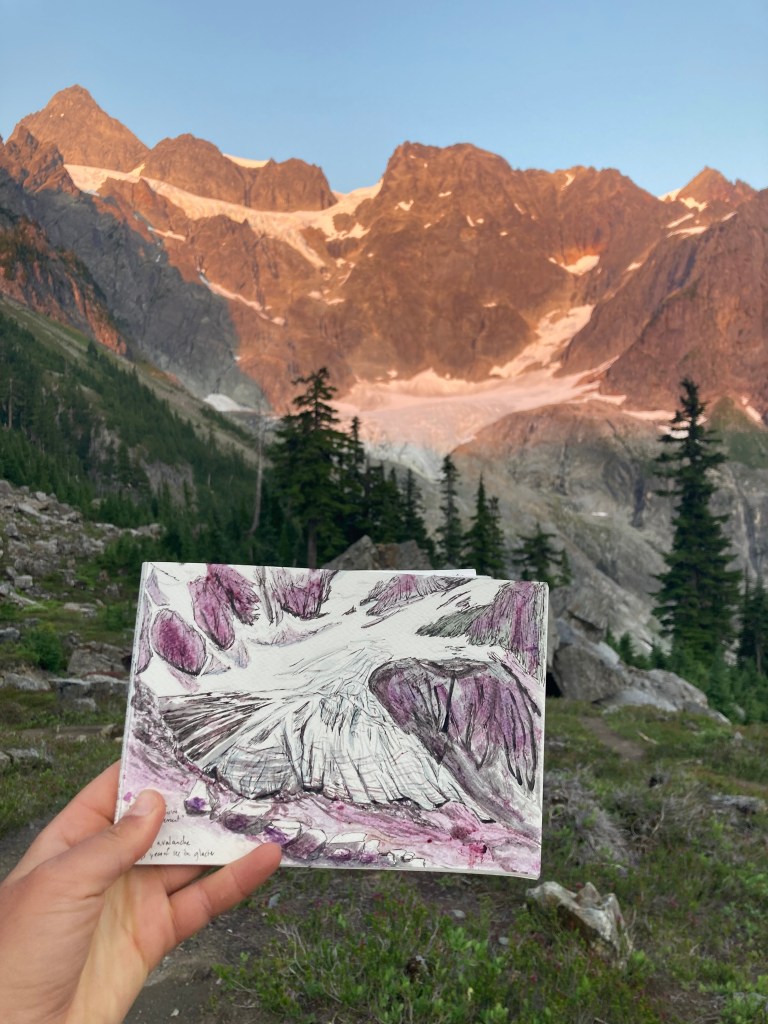

Find a location where temperatures are cold for at least 7 months of the year. This location also needs to have substantial snowfall and ideally where addtiional snow is added via avalanches or wind depostion. With these ingredients on hand, let stand for a few decades, while the snow accumulates to a thickness of at least 20 m. A key step in the recipe is the transformation of snow to ice under its own weight and with some meltwater percoloation and refreezing. Unlike bread dough you do not need stir or kneed during this period. Once there is a volume . For the glacier to persist the glacier must retain accumulation across a significant portion of its surface by the end of summer. To maintain its size we have observed this percentage to vary from 50-70% on North Cascade glaciers. The lack of a persistent accumulation zone will lead to loss of that glacier. of 500,000 m3 you are either a glacier or at the threshold of being a glacier depending on how steep the underlying slope is. Unlike rolling out a pie crust, this does not need to be an even thickness, or made on a flat surface. As the glacier matures it will develop crevasses indicating movement, which is an essential characteristic of a glacier. It is not a passive feature, its movement allows it to begin to sculpt its landscape.

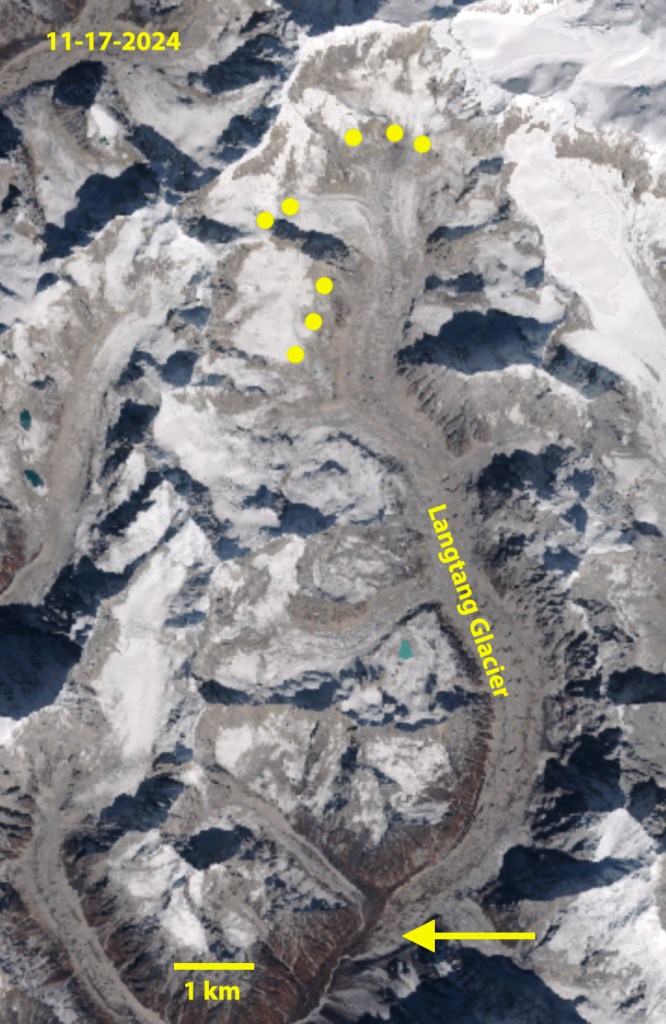

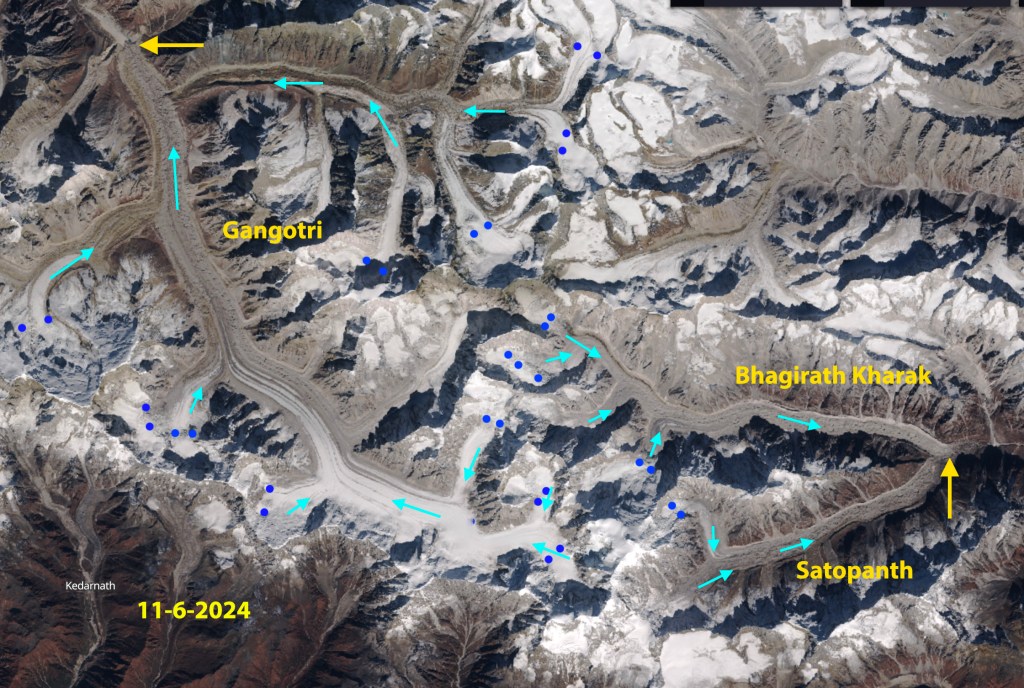

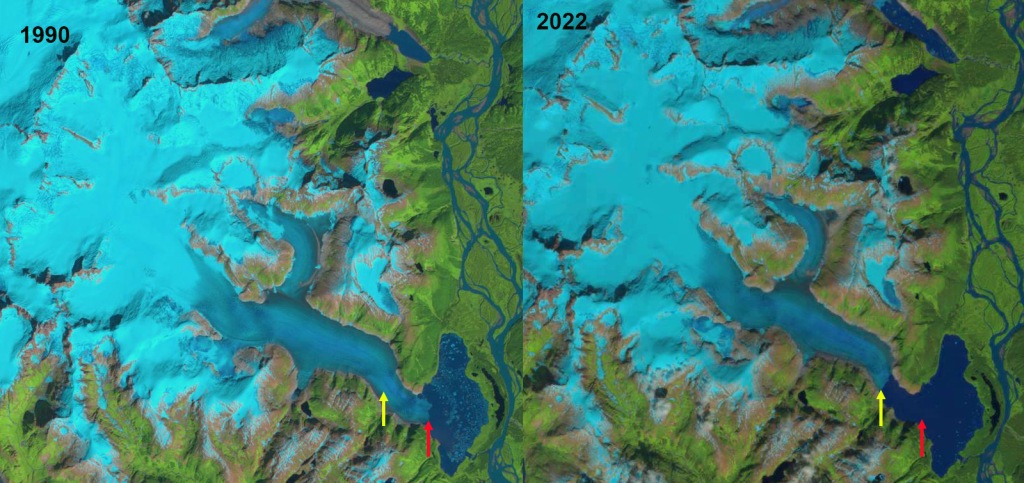

Current Glacier Loss in North Cascade Range, Washington

Many centuries or millenia later, the glacier has become a critical part of the landscape. Yet, changing climate is leading to the loss of many. In the North Cascades glaciers have been losing close to 1% of their volume annually over the last 40 years, with the rate rising to over 2% in the last decade. The glaciers cover 200 km2 almost all of which are in steep high elevation Wilderness areas not proximate to roads. In 2010 we noted that 2/3 of North Cascade glaciers could not survive current climate. Today this percentage has increased to more than 90%. There are 31 glaciers in the range that I completed observations on in the 1980s that are now gone. Our annual field expedition has noted the glaciers losing ~1.5 m of thickness annually in the last decade.

Are there any Preservatives we can add to the Recipe?

What would it take to preserve the Easton Glacier in the North Cascades?

The largest snowmaking operation in North America is at Killington Ski Area, VT. At maximum capacity they can convert 35,000 m3 of water into snow per day. Given that Easton Glacier has an area of 2.5 km2 and has been losing 1.5 m water equivalent thickness per year, 3.75 million m3 of water equivalent snow has to be produced.This would take 108 days at maximum capacity of the more than 2000 snow guns. This ignores enviornmental laws and the logistics of water supply, piping, snow gun placement and electricity. This all in an environment of harsh weather with avalanches and crevasses.

To cover the glacier with geotextiles during the summer, requires 2.5 million square meter of material that would be to installed each summer and removed each winter to allow accumulation, of course summer recreation would not be practical on the glacier. The geotextiles do not last long in these conditions and cost ~$2 per square meter. How to anchor these in place and connect on a crevasse glacier would be very difficult, which is why usually only a portion of the glacier near the terminus is covered, which does not help the overall situation of glacier loss.

There are many more glaciers in this range and around the world where this same confounding logistical challenges make any artificial attempts at preservation ridiculous beyond a few isolated glaciers that are already close to existing infrastructure.

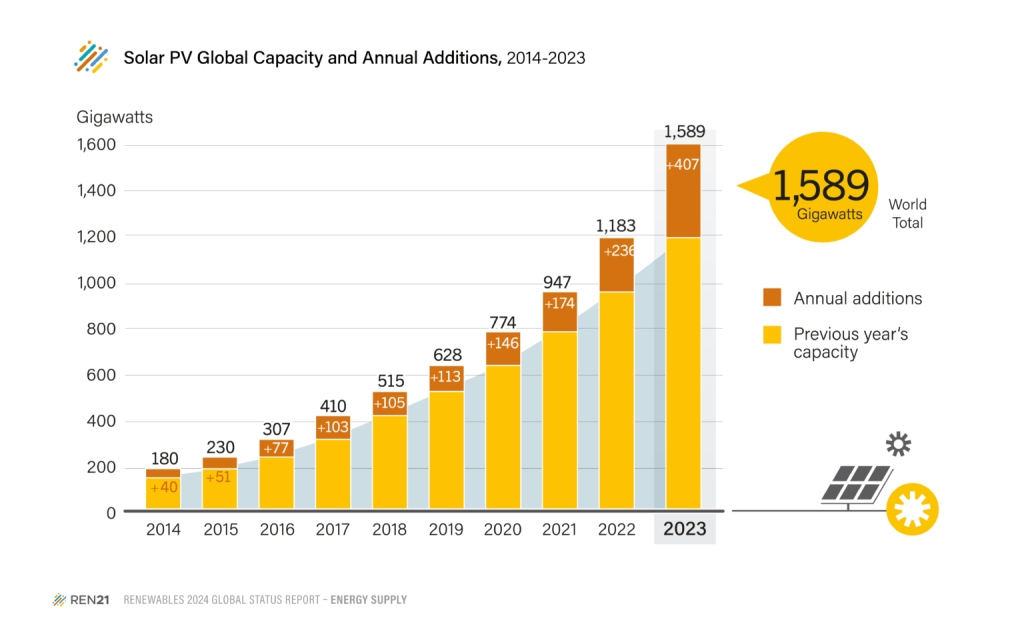

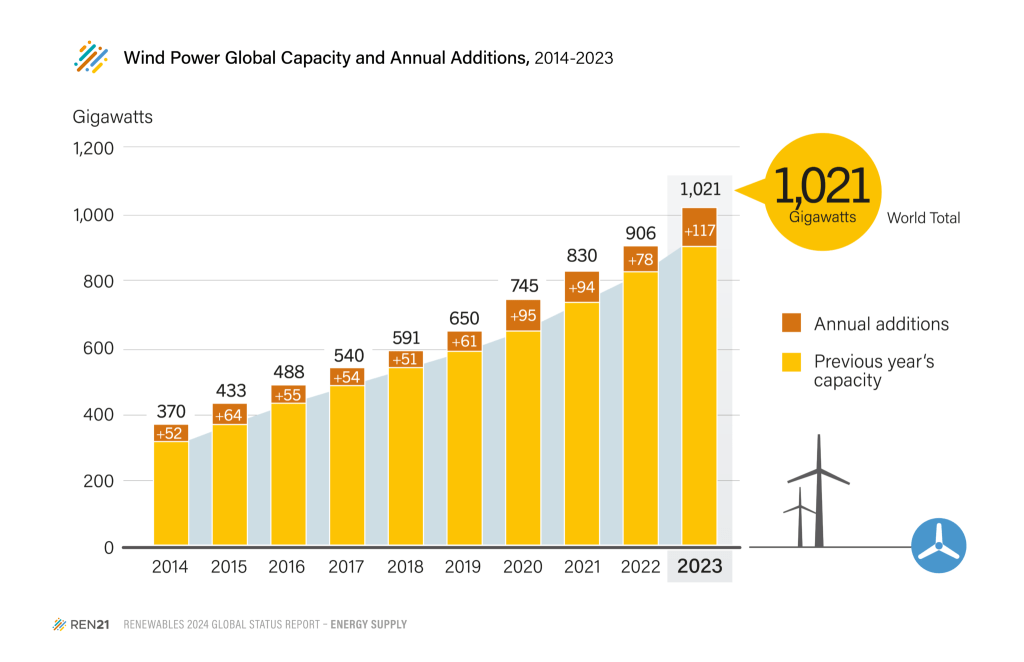

When I began this work in 1984 solar power and wind power did not exist, these are not the only renewable sources of power, and just one of many approaches to reducing CO2 emissions, but they are illustrative of rapid growth from insignificance. The Renewalbes 2014 Global Status Report and the Renewables 2024 Global Status Reports provides measures of renewaable energy production over the last decade. Global capacity for Solar Photovoltaic energy production has risen from 4 GW in 2004 to 190 GW in 2014 and then to 1600 GW in 2023. Global Capacity for Windpower has risen from 48 GW in 2004 to 370 GW in 2014 and in 2023 was 1020 GW. In 2023 alone over 500 GW was added to these two sources combined. See below for charts from this report on increased capacity. This is a preservative under development that can work with continued emphasis and in concert with other items such power grid infrastructure improvement and electric/hybrid automobile manufacturing expansion.