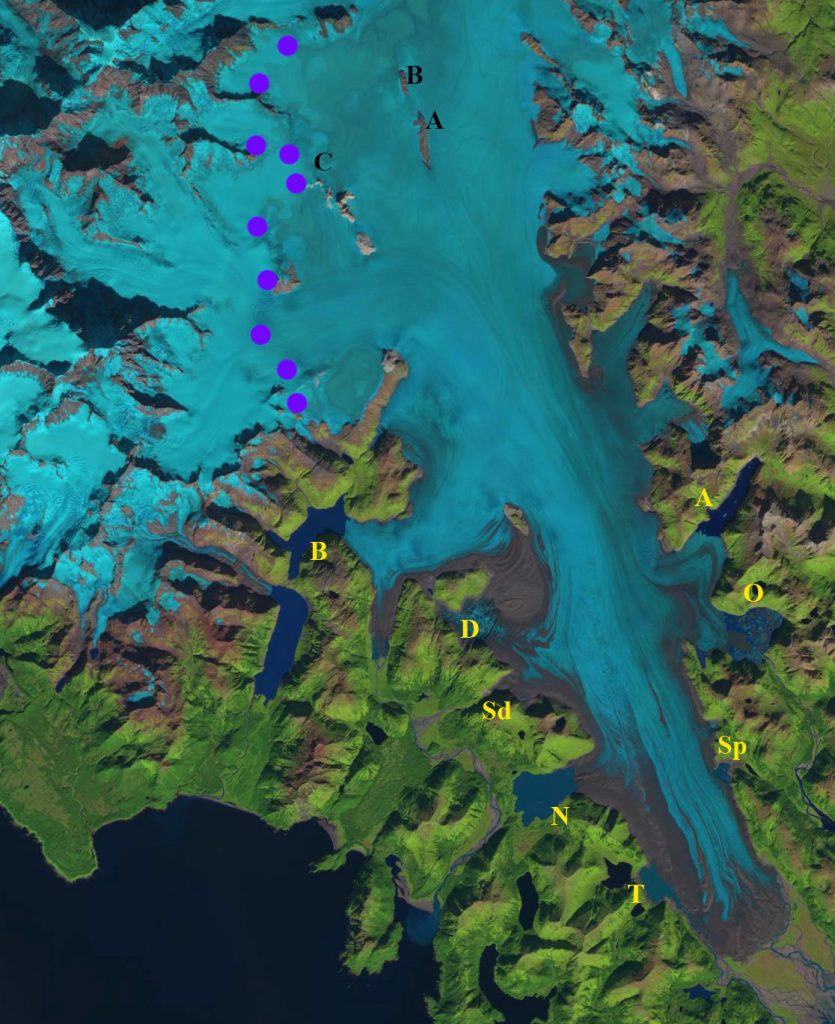

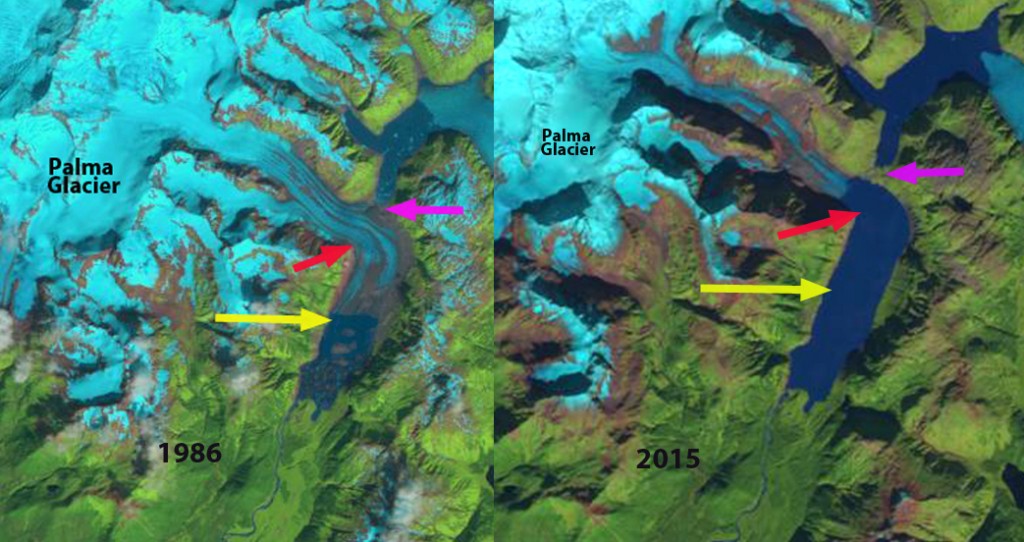

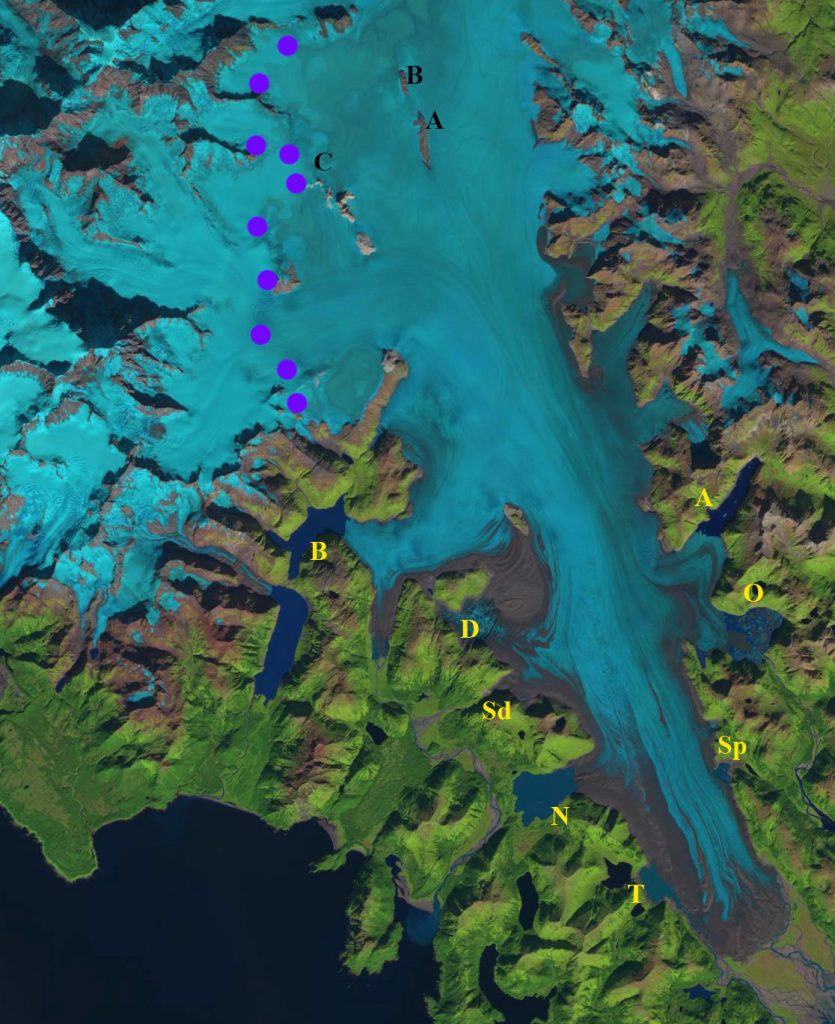

Emergence of Nunataks at Point A, B and C at 850 m on Brady Glacier from 1986 and 2018 Landsat Images. Transient snowline on 9/21/2018 indicated by purple dots.

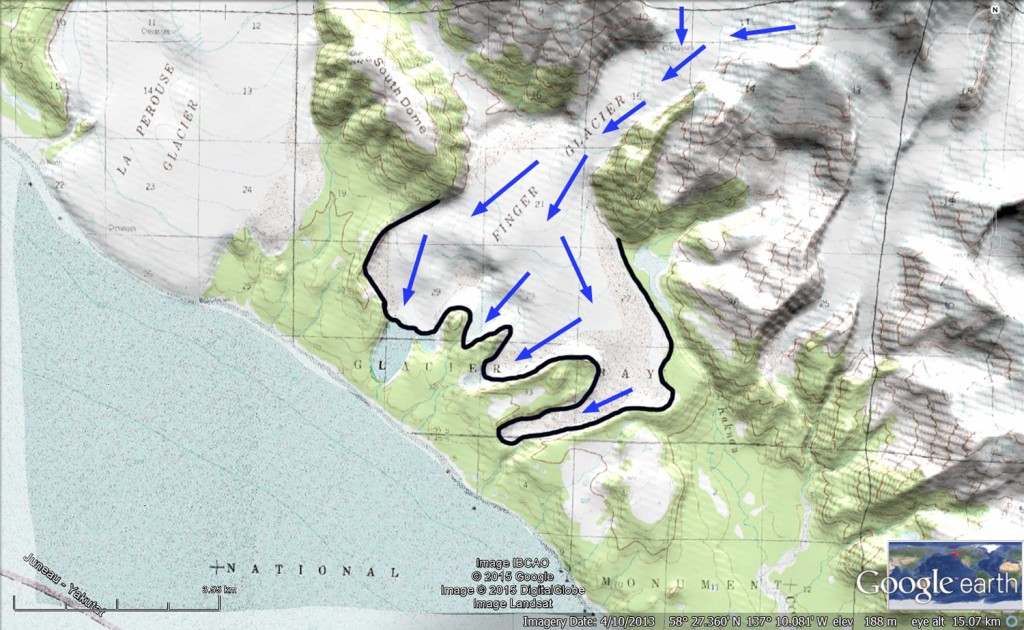

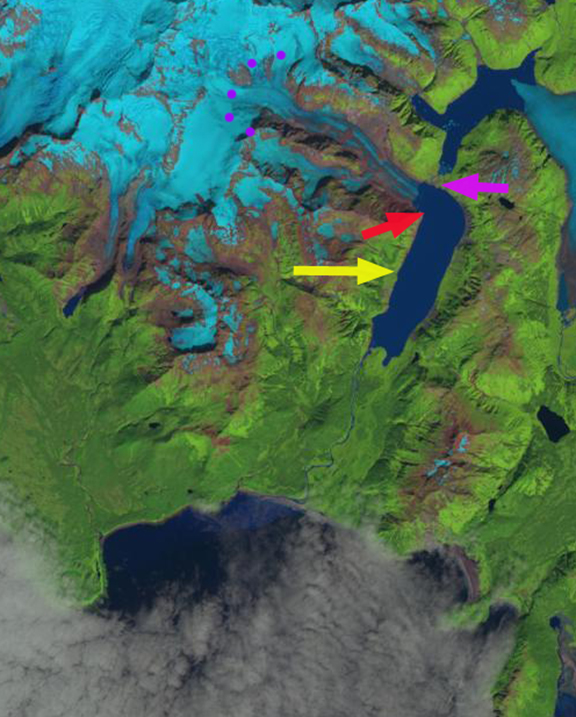

Brady Glacier, is a large Alaskan tidewater glacier, in the Glacier Bay region that is beginning a period of substantial retreat Pelto et al (2013). Pelto et al (2013) noted that the end of season observed transient snowline averaged 725 m from 2003-2011, well above the 600 m that represents the equilibrium snowline elevation, for the glacier to sustain its current size. In 2015, 2016 and 2018 the snowline has been at 900-1000 m. This is leading to thinning across of what was much of the accumulation zone. Here we examine Landsat images from 1986 to 2018 to identify signs of this thinning.

In 1986 Point A and B have insignificant rock exposure, while C has a limited single rock nunatak. By 2000, below there is bedrock exposed west of Point A and B, with two small nunataks near C. By 2015 there is a 2 km long bedrock ridge at Point A and a ~1 km long bedrock ridge at Point B. The snowline in 2015 is just above Point B and C at 900 m. In 2016 on Oct. 1 2016 after the end of the typical melt season the snowline is at 900 m. In 2018 the snowline on Sept. 21 is at 1000 m. At Point A the bedrock Ridge is now 2300 m long and up to 300 m wide. At Point A the ridge is 1100 m long. At Point C a third nunatak has emerged and the series of nunataks will soon merge into a single ridge.

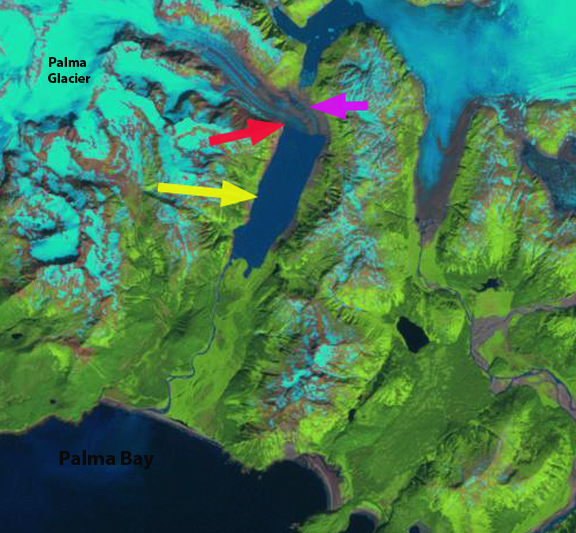

The persistent high snowlines indicate the consistent accumulation zone is now above 900 m, below this point thinning will continue. The mean elevation of the glacier is at 720 m and thinning is significant below 1000 m from 1995-2011(Johnson et al 2013). That far less than 50% of the glacier is retaining snowpack and widespread thinning will drive further retreat of the distributary glacier termini in expanding lakes noted by Pelto et al (2013) and a the 2016 blog post. Brady Glacier abuts the adjacent Lampugh Glacier that has and will be impacted by a large landslide.

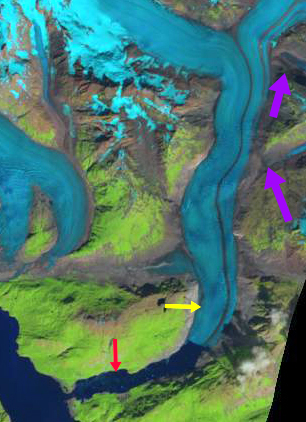

Trick Lakes: In 1986 North and South Trick Lake are proglacial lakes in contact with the glacier. By 2016 the two lakes are no longer in contact with the glacier, water levels have fallen and a third lake East Trick Lake has formed. The more recently developed East Trick Lake is the current proglacial Trick Lake, a large glacier river exits this lake and parallels the glacier to the main Brady Glacier terminus, going beneath the glacier for only several hundred meters.

North Deception Lake had a limited area in 1986 with no location more than 500 m long. By 2016 retreat has expanded the lake to a length over 2 km. The width of the glacier margin at North Deception Lake will not change in the short term, but the valley widens 2 km back from the current calving front, thus the lake may grow considerably in the future.

South Dixon Lake This new lake does not have an official name. It did not exist in 1986, 2004, 2007 or 2010. It is nearly circular today and 400 m in diameter.

Dixon Lake: It is likely that retreat toward the main valley of the Brady Glacier will lead to increased water depths at Dixon Lake, observations of depth of this lake do not exist. Retreat from 1986 to 2016 has been 600 m.

Bearhole LakeBearhole Lake is expanding up valley with glacier retreat, and there are no significant changes in the width of the valley that would suggest a significant increase in calving width could occur in the near future. Currently the lake is 75 m deep at the calving front and there has been a 1400 m retreat since 1986 Capps et. al. (2013).

Spur Lake:It is likely that retreat toward the main valley of the Brady Glacier will lead to increased water depths at Spur Lake. the depth has fallen as the surface level fell from 1986-2016 as the margin retreated 600 m, leaving a trimline evident in the 2016 imagery.

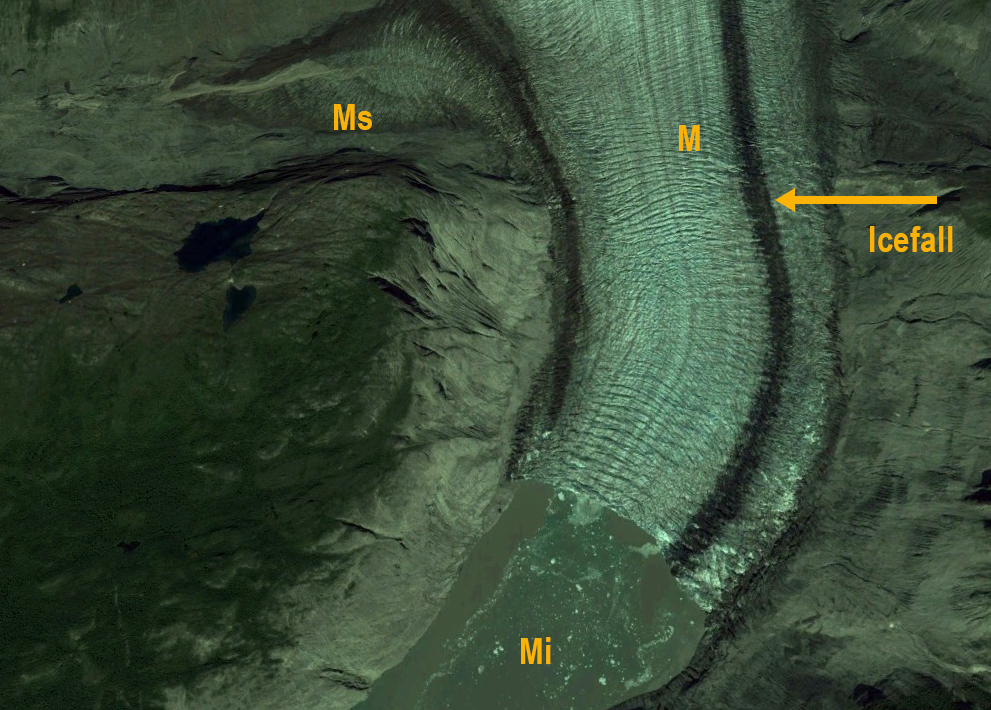

Oscar Lake has experienced rapid growth with the collapse of the terminus tongue. Depth measurements indicate much of the calving front which has increased by an order of magnitude since 1986 is over 100 m. The tongue as seen in 2014 Google Earth image will continue to collapse and water depth should increase as well. The central narrow tongue has retreated less than 200 m since 1986, but the majority of the glacier front has retreated more than 1 km since 1986.

Abyss Lake: Continued retreat will lead to calving width expansion> The retreat from 1986 to 2016 has been 400 m. The water depth has been above 150 m at the calving front for sometime and should remain high.

Emergence of Nunataks at Point A, B and C at 850 m on Brady Glacier from 2000 and 2015 Landsat Images. Transient snowline on 9/21/2018 indicated by purple dots.

Landsat image of Brady Glacier on 9/21/2018 indicating the snowline (purple dots) and the emerging nunataks at Point A-C. Lakes noted are: A=Abyss, B=Bearhole, D=Dixon, N=North Deception, O=Oscar, Sd=South Dixon, Sp=Spur, T=Trick.

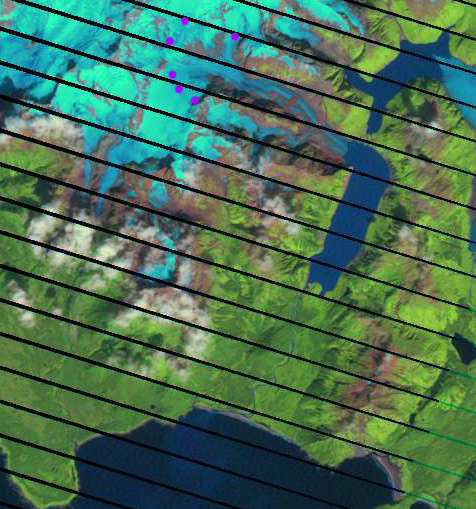

Landsat image of Brady Glacier on 10/1/2016 indicating the snowline (purple dots) and the emerging nunataks at Point A-C.