Grand Pacific Glacier in 1984 and 1999 Landsat images. Red arrow indicates the front of the clean ice flow of the Grand Pacific that also marks its lateral boundary with Ferris Glacier. B and C indicate locations where tributary tongues have been retreating from the main glacier. M is the Margerie Glacier.

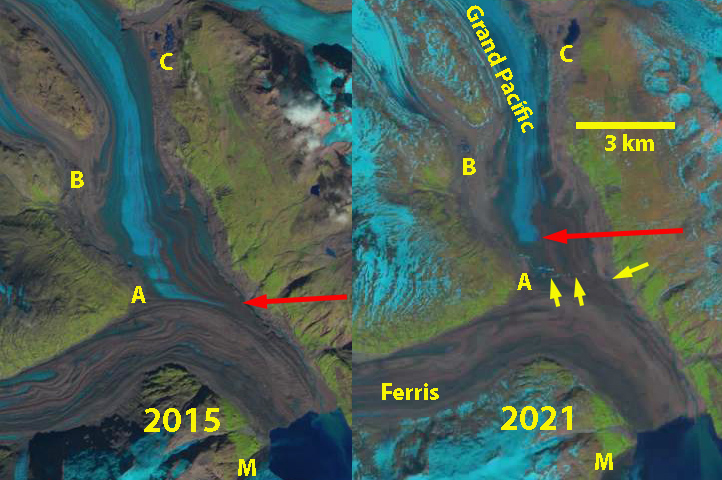

Grand Pacific Glacier in 2015 and 2021 Landsat images. Red arrow indicates the front of the clean ice flow of the Grand Pacific that also marks its lateral boundary with Ferris Glacier and the front of its active ice. Yellow arrow indicates outlet stream that is now beginning to separate the glaciers. B and C indicate locations where tributary tongues have been retreating from the main glacier. M is the Margerie Glacier.

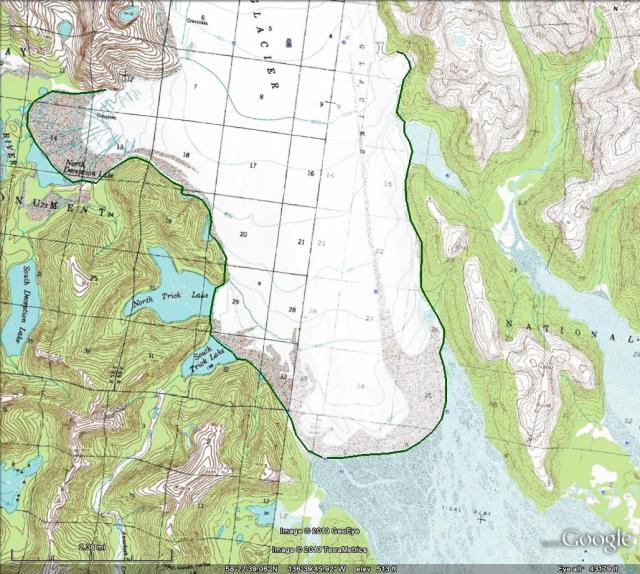

The Grand Pacific joins with Ferris Glacier before ending at the head of Tarr Inlet in a ~1.9 km wide glacier front and 20-50 m high ice front. William Field observed the glacier advancing steadily from the 1930’s-1968 at 35 m/year , extending ~.0.5 km across the US/Canada boundary. This advance continued behind its protective shoaling moraine/outwash plain until it was 1.5-1.6 km across the national boundary and just meeting the Margerie Glacier. A slow recession of 200 m has occurred since, with the current terminus having a width of 1.8 km, most in shallow water or terminating on a tidal flat. The Grand Pacific Glacier has been thinning for more than 50 years, which is leading to the recession, though not nearly as significant at for Melbern Glacier which it shares a divide with. Clague and Evans (1993) noted a 7 km retreat of Melbern Glacier from 1970-1987, and a 5.25 km retreat from 1986-2013 (Pelto, 2011-2017). The mass loss of the Grand Pacific Glacier system is part of the 75 Gt annual loss of Alaskan glaciers that make this region the largest alpine glacier contributor to sea level rise from 1984-2013 (Larsen et al 2015).

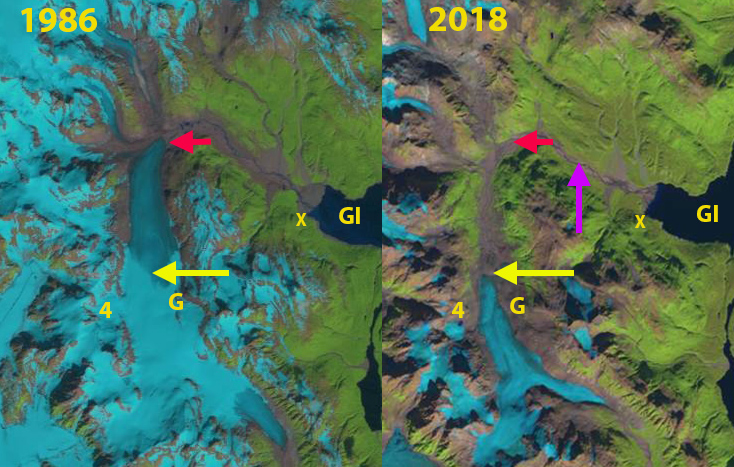

William Field reported that Grand Pacific Glacier comprised 80% of the joint glacier front with Ferris Glacier in 1941, declining to 40% in 1964. In 1984 Landsat imagery illustrates that the Grand Pacific is still supplying ice to the glacier front but only comprises 25% of the ice front. In 1999 this has diminished to 20% of the ice front, that is now entirely on an outwash plain above the tidal level. Tributary C has disconnected from Grand Pacific Glacier between 1984 and 1999, and tributary B has retreated substantially from the Grand Pacific. By 2015 the junction of the Ferris and Grand Pacific Glacier indicates all flow of the latter is diverted east along the Ferris margin and does not reach the ice front. There is a band of clean glacier ice that reaches the junction in 2015 and in the 2016 Sentinel image, but no longer reaches the eastern margin. In 2016 the glacier outlet stream along the west side of the Grand Pacific goes under the glacier to the east margin near the junction. By 2018 the surface exposed section of the stream extends ~700 m across the Grand Pacific Glacier before going beneath the glacier along the Ferris/Grand Pacific margin. In 2021 the glacier outlet stream cuts halfway across the glacier before going beneath and emerges prior to reaching the east margin, note yellow arrows below on the Sentinel image . The clean ice area no longer reaches the junction with the Ferris Glacier in 2021. The rapid expansion of the surficial outlet stream that is physically separating the two glacier will continue to cut across the entire width of the Grand Pacific Glacier. This glacier no longer has a connection to the Pacific Ocean, and no longer presents a grand front. The retreat is limited in distance compared to Grand Plateau or Fingers Glacier, but the separation is dramatic.

Sentinel 2 image of Grand Pacific Glacier in July 2016, yellow arrow indicates glacier outlet stream beginning to transect glacier.

Sentinel 2 image of Grand Pacific Glacier in August 2018, yellow arrow indicates glacier outlet stream expanding across glacier.

Sentinel 2 image of Grand Pacific Glacier in July 2016, yellow arrow indicates glacier outlet stream nearly transecting the entire width of the Grand Pacific Glacier front/margin with Ferris Glacier.