2025 Field Season: For the 42nd consecutive summer we are heading into the field to measure and communicate the impact of climate change on North Cascade glaciers. This year an overall focus of the project is supporting the UN’s “International Year for Glaciers’ Preservation”. This means focusing on glaciers that have disappeared and are in critical danger of disappearing in the next decade. Jill Pelto, Art Director and Mauri Pelto, Science Director

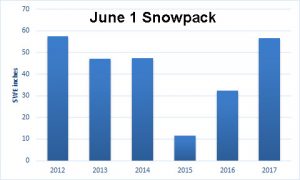

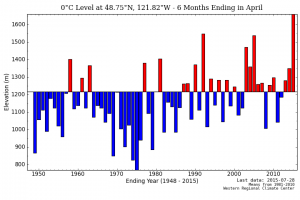

This field season follows the 2021-2024 seasons that featured either historic heat waves and/or periods of extended warm weather. The heat led to a greater exposure of bare ice on glaciers with a higher albedo and greater density. The observed melt rates are 7-9 cm/day water equivalent during warm weather events vs 4-6 for snow surfaces. This led to substantial mass losses on North Cascade glacier for the four years of over ~6 m.

Science objectives: We will complete detailed measurements on 10 glaciers, three of which are part of the World Glacier Monitoring Service reference glacier network (48 glaciers globally), which have 30+ consecutive years of mass balance observations. This summer we will have an opportunity to assess the long-term ramifications of the 2013-2024 period of unprecedented mass balance losses and associated glacier changes, with detailed mass balance, crevasse depths and glacier surface elevation profiling. We also focus on the impact of diminishing glacier size on downstream runoff.

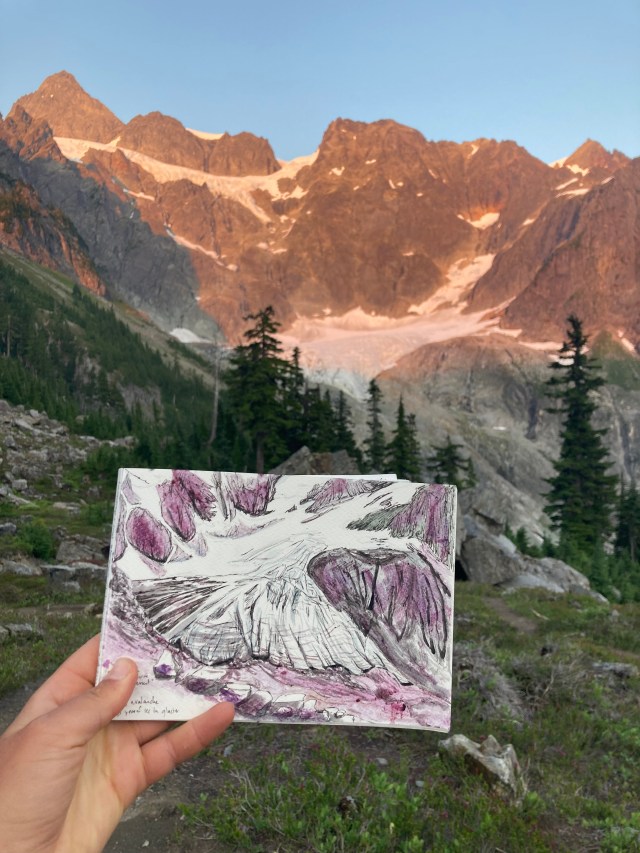

Art Objectives: We will collaborate with several artists who will join us for a portion of the field season. They will be able to create their own work about the landscape and the science or may join us for fieldwork and make plans for future artwork. We hope to use this art to share our research with a broader audience and highlight the beauty and importance of these places.

Communication Objectives: We will leverage the brands of our expedition sponsors and the focus on vanishing glaciers that the UN brings this year. These organizations can help spread our message. We will utilize a combination of artists and scientists to tell the story.

Field Team 2025:

Jill Pelto (she/her) is an artist and scientist from New England who grew up loving winter sports and trips to the mountains. She incorporates scientific research and data into paintings and prints to communicate environmental changes. Her multi-disciplinary work weaves visual narratives that reveal the reality of human impacts on this planet. She completed both her B.A. degrees in Studio Art and Earth and Climate Science, and her M.S. focused on studying the stability of the Antarctic Ice Sheet at the University of Maine, spending two field seasons at a remote camp in the southern Transantarctic Mountains. Jill will be joining the project for her 15th field season. She is excited about continuing to document the change in North Cascade glaciers that she has witnessed each of the last ten years — through science and art.

Jill’s 2025 Paintings inspired by our work about the Skykomish River Watershed and the Nooksack River Watershed.

Mauri Pelto (he/him) has directed the project since its founding in 1984, spending more than 800 nights camped out adjacent to these glaciers. He is the United States representative to the World Glacier Monitoring Service. For 15 years he has been author of the blog “From a Glacier’s Perspective”, and associate editor for three science journals. He is on the Science Advisory Board for NASA’s Earth Observatory. His primary position is Associate Provost at Nichols College, where he has been a professor since 1989. He either runs on trails or skis on alpine and cross country trails every day.

Emmett Elsom (he/him) is an environmental science student at Western Washington University from Portland, Oregon. Growing up mountaineering and backpacking in the Cascade Range, he developed a love for the region and a fascination with the complexities of its ecosystems. In 2024 he had an opportunity to work In the field with the Oregon Glaciers Institute, assisting with SNOTEL data collection and fieldwork. This year, he is looking forward to broadening his understanding of the ecological role of glaciers and their melt across the Pacific Northwest, and the power of utilizing art in science.

Caitlin Quirk (she/her) is a Masters student of Environmental Humanities at the University of Utah. She writes essays and poetry about socio-environmental justice, land relations, and political ecologies of climate change. Before graduate school, Caitlin worked as a mountaineering instructor and environmental researcher. Through these roles, she formed deep relationships with glaciers throughout the Pacific Northwest.

Katie Hovind (she/her) is an environmental science student at Western Washington University. She feels a deep connection to the Cascade mountains and their watersheds from growing up in this region, and hopes to share their beauty and importance with others. She was a field assistant with NCGCP last year, and is excited to continue collaborating this year to explore ways science and art can evoke caring—for protection of natural spaces and response to the climate crisis. This season, she will help conduct a vegetational succession study at the Easton’s terminus to observe the changing alpine plant growth in the wake of a receding glacier.

Margaret Kingston: is an oil painter and art educator from Winthrop, Washington. Originally from New Hampshire, she moved 3000 miles with her husband Jonathan Baker to the Methow Valley after visiting the North Cascades National Park. Landscapes of the Pacific Northwest have been her inspiration for the past 13 years, captured first through a photo then realistically painted on canvas. As a backcountry skier, hiker, and biker she captures the energy of places these activities take you. With funding from the Mary Kiesau Fellowship Grant, Margaret will plein air paint on site in honor of her friend Mary Kiesau. Her observations during time spent with the North Cascade Glacier Climate Project will be shared through the resulting artwork and at a community event in the Methow Valley. Learn more about Margaret Kingston’s work at MkOilPaintings.com

Claire Sianna Seaman (she/her) is a painter, filmmaker, and printmaker from Leavenworth, WA. She holds a BA from Smith College in Studio Art, with a concentration in Climate Change. She is currently earning her MA in Human Geography at the University of British Columbia. Claire has been featured in the Wild and Scenic Film Festival Art Exhibition and received an Artist Trust GAP Award. She worked with scientists from the University of Washington Climate Impacts Group to create an art piece that imagined climate resiliency in the Pacific Northwest. This piece is currently part of the 5th National Climate Assessment Art x Climate Gallery on display at the Smithsonian Natural History Museum in Washington, D.C https://www.clairesianna.com/

2025 Schedule

July 28: Hike In Columbia.

July 29: Columbia Glacier survey

July 30: Hike Out Columbia/Hike in Lower Curtis

July 31: Lower Curtis Glacier Survey

Aug. 1: Hike out, Hike in Ptarmigan Ridge

Aug. 2: Sholes Glacier

Aug. 3: Rainbow Glacier

Aug. 4: Rainbow Glacier

Aug. 5: Hike out. Hike in Easton Glacier (Resupply in Bellingham WA)

Aug. 6: Easton Glacier

Aug. 7: Deming Glacier

Aug. 8: Easton Glacier

Aug. 9: Easton Glacier

Aug. 10: Hike in Mount Daniels

Aug. 11: Mount Daniels Survey

Aug. 12: Ice Worm Glacier Survey-Exit

Assessing Crevasse Depth on Easton Glacier