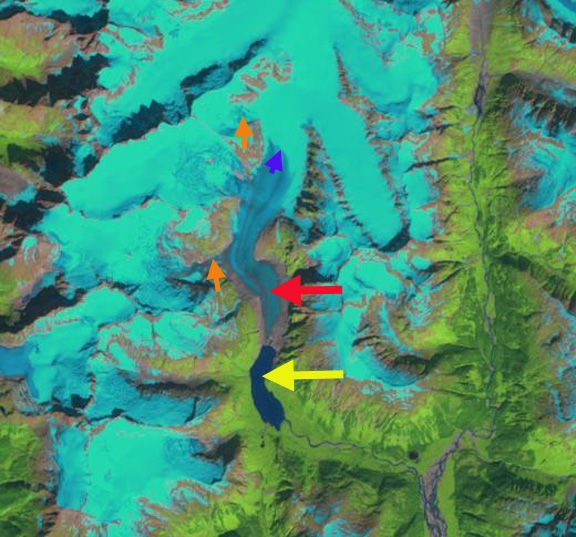

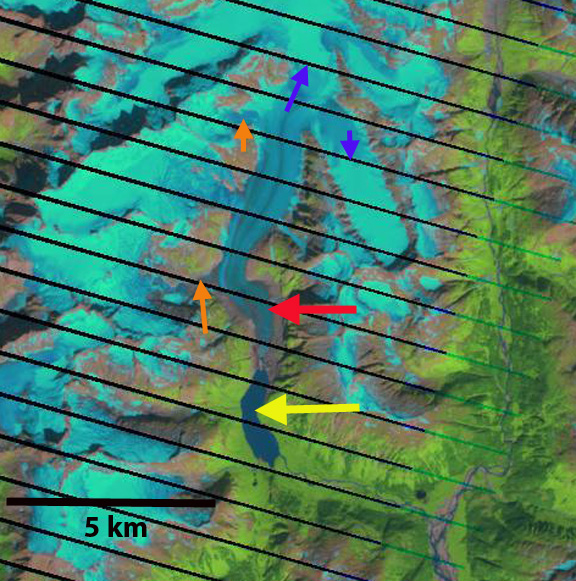

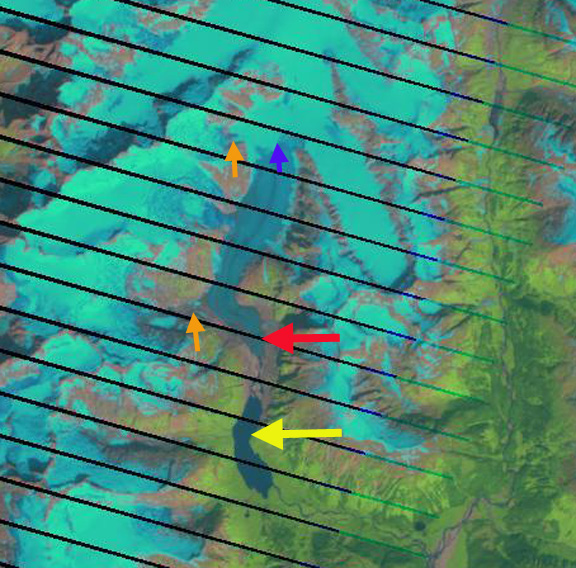

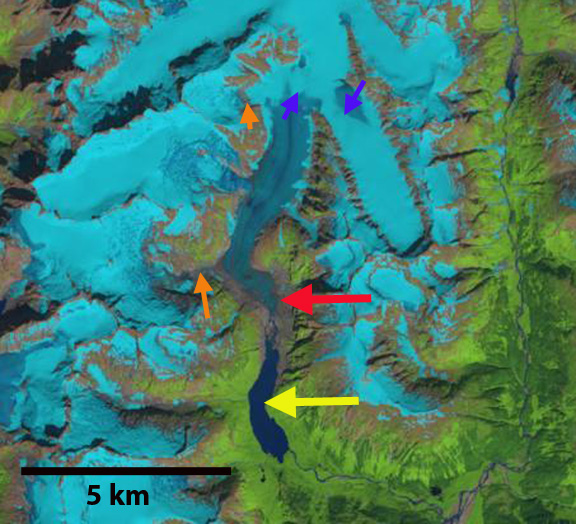

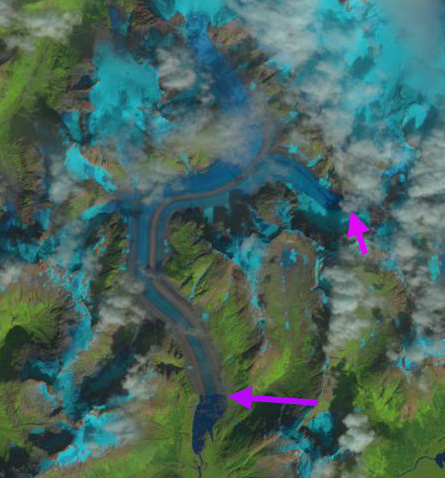

Sholes Glacier snowcover Aug. 5, 2013 (Jill Pelto) and Sholes Glacier July 23, 2015 (Oliver Grah)

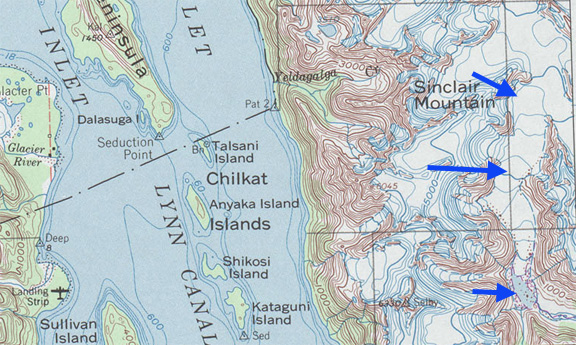

For the 32nd straight summer we will be investigating North Cascade glaciers and their response to climate change over the next three weeks (that means no new posts until Aug. 20). In 1984 the program was initiated to study the impacts of climate change across an entire mountain range, instead of on just one glacier. This had been a high priority of the National Academy of Science, I felt I could address. The glaciers in the North Cascades provide water resources for irrigation, hydropower, salmon and municipal supply. During our 32 years we have seen the loss of 25% of the entire glacier volume of the range. Unfortunately 2015 is almost certainly going to be the worst year during this period. We will likely lose over 5% of the volume of these glaciers in one year. The problem has been high freezing elevations in the winter, note the difference from other years below. Because of the drought conditions glaciers are even more crucial to runoff, note the daily spike in flow due to glacier melt in the Nooksack River in July, black arrows. Blue arrow indicates rain storm.

Freezing levels on Mount Baker during winter 2015 versus previous winters. Nooksack River discharge from the USGS in July.

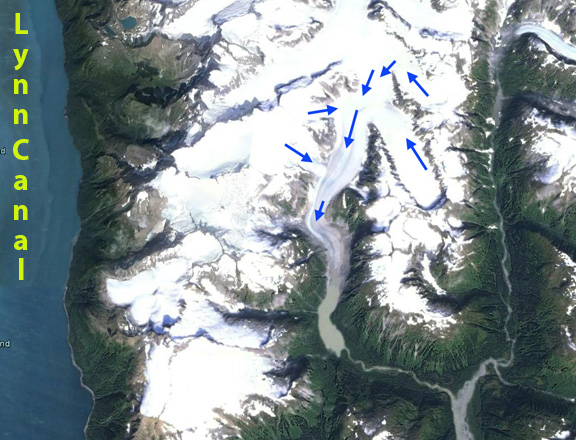

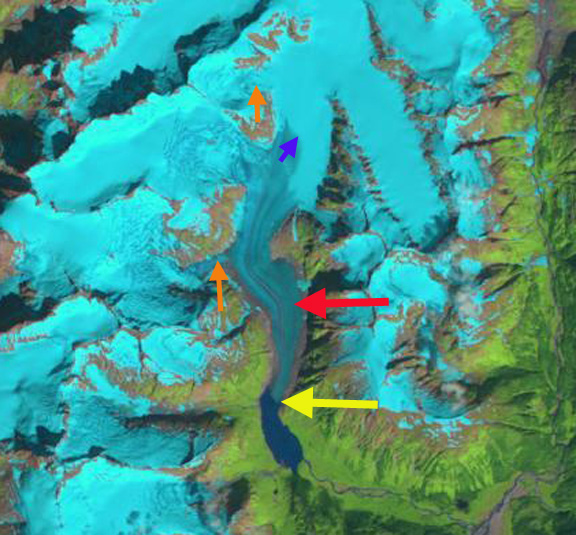

This has been followed by the warmest June and now July the region has seen. This has led to record low streamflow from either rain, groundwater or snowpack from non-glacier areas. The result is that in glacier fed basins glacier runoff which is above normal because of the warm temperatures is even more important. We are measuring flow below glaciers and melting on glaciers to quantify the percent of total flow contributed by glaciers. In 2014 in the North Fork Nooksack River glaciers contributed more than 40% of total stream discharge in the river on 21 days, all in August and September. We again with the Nooksack Indian Tribe will be examining the issue, particularly at Sholes Glacier. We will also be measuring the mass balance, terminus change and mapping ten glaciers we visit every year, including Columbia Glacier seen below.

Terminus of Columbia Glacier and accumulation zone looking bare in 2005, the lowest snowpack year of the last 32 until this year

The glaciers are all in Wilderness areas which means no motorized vehicles or equipment, we have to hike everything in. This has provided the opportunity to spend over 600 nights in a tent examining the glaciers, hiking/skiing over 3000 miles across the glaciers, and eating oatmeal each morning for breakfast. It has also provided the opportunity to train and work with more than 60 different scientists. This year the field team consists of Erica Nied from the University of Colorado, Tyler Sullivan from the University of Maine, Jill Pelto from the University of Maine for the seventh year and myself for the 32nd year. We will be joined at times by Justin Wright, Oregon State, Tom Hammond, University of Washington, Ben Pelto University of Northern British Columbia, Oliver Grah and Jezra Beaulieu of the Nooksack Indian Tribe. Below are three videos from last year that illustrate: 1: Visual report on initial 2015 findings 2: How and why we measure mass balance.3. The Nooksack Indian Tribe perspective on threats of glacier runoff and our measurements of it.