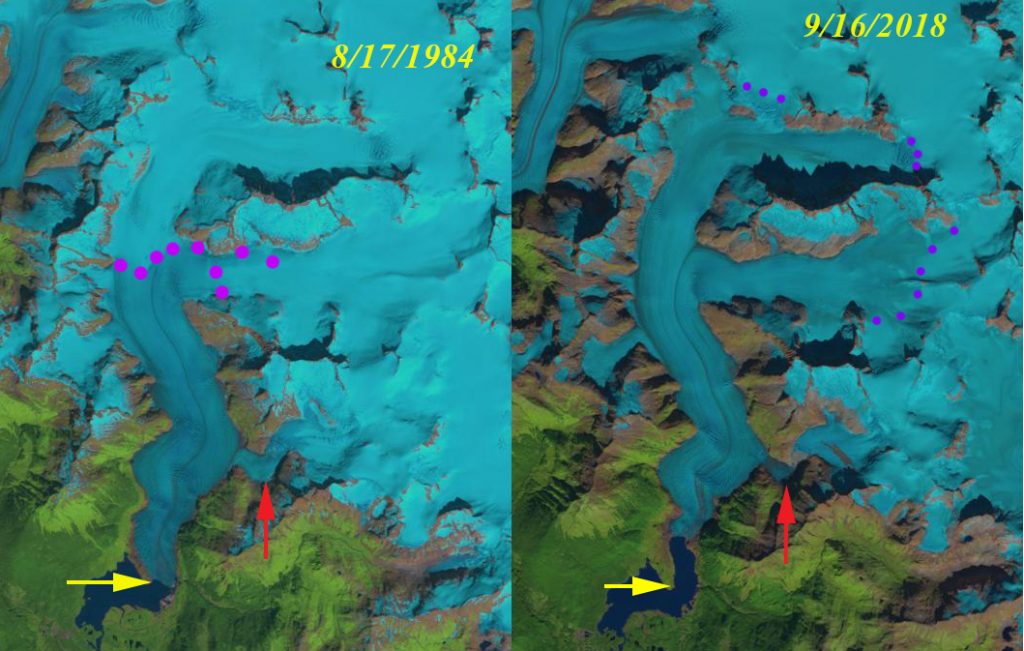

Mendenhall Glacier in Landsat images from 1984 and 2018. Yellow arrows indicates 1984 terminus location, read arrow the Suicide Basin tributary and the purple dots the snowline.

Mendenhall Glacier is the most visited and photographed terminus in the Juneau Icefield region. The glacier can be seen from the suburbs of Juneau. Its ongoing retreat from the Visitor Center and the expansion of the lake it fills is well chronicled. Here we document the rise in the snowline on the glacier that indicates increased melting and reduced mass balance that has driven the retreat. The change in snowline from 1984-2018 and the associated retreat are documented. The snowline as July begins in 2019 is already in the end of summer range. In 1984 I had a chance to ski across the upper portion of this glacier.

Top of the Mendenhall Glacier at 1500 m looking towards ocean in 1984.

Mendenhall Lake did not exist until after 1910, in 1948 it was 2.2 km across and by 1984 the lake was 2.7 km across. Boyce et al (2007) note the glacier had two period of rapid retreat one in the 1940’s and the second beginning in the 1990’s, both enhanced by buoyancy driven calving. The latter period has featured less calving particularly in the last decade and is a result of greater summer melting and a higher snowline by the end of the summer, which has averaged 1250 m since 2003 vs 1050 m prior to that (Pelto et al, 2016). In 2005, the base of the glacier was below the lake level for at least 500 m upglacier of the terminus (Boyce et al (2007). This suggests the glacier is nearing the end of the calving enhanced retreat. It is likely another lake basin would develop 0.5 km above the current terminus, where the glacier slope is quite modest.

Terminus of Mendenhall Glacier before the 1982 field season on the Juneau Icefield.

The glacier in 1984 ended at the tip of a prominent peninsula in Mendenhall Lake. The snowline is at 950 m. In 1984 with the Juneau Icefield Research Program we completed both snowpits and crevasse stratigraphy that indicated retained snowpack at the end of summer is usually more than 2 m at 1500-1600 m. The red arrow indicates a tributary that joins the main glacier, where Suicide Basin, currently forms. In 2014 the snowline in late August is at 1050 m. The terminus has retreated to a point where the lake narrows, which helps reduce calving. In 2015 the snowline is at 1475 m. In 2017 the snowline reached 1500 m. There is a small lake in Suicide Basin. In September 2018 the snowline reached 1550 m the highest elevation the snowline has been observed to reach any year. In Suicide Basin the lake drained in early July. In 2018 Juneau Icefield Research Program snowpits indicates only 60% of the usual snowpack left on the upper Taku Glacier, near the divide with Mendenhall Glacier. On July 1. 2019 the snowline is already as high as it was in late August of 1984. This indicates the snowline is likely to reach near a record level again. The USGS and NWS is monitoring Suicide Basin for the drainage of this glacier melt filled lake. In 2019 the lake rapidly filled from early June until July 8, water level increasing 40 feet. It has drained from July 8 to 16 back to it early June Level. The high melt rate has thinned the Mendenhall Glacier in the area reducing the elevation of the ice dam and hence the size of the lake in 2019 vs 2018.

The snowline separates the accumulation zone from the ablation (melting) zone and the glacier needs to have more than 60% of its area in the accumulation zone. The end of summer snowline is the equilibrium line altitude where mass balance at the location is zero. With the snowline averaging 1500 m during recent years this leaves less 30% of the glacier in the accumulation zone. This will drive continued retreat even when the glacier retreats from Mendenhall Lake. The declining mass balance despite retreat is evident across the Juneau Icefield (Pelto et al 2013). Retreat from 1984-2018 has been 1900 m. This retreat is better known, but less than at nearby Gilkey Glacier and Field Glacier.

Mendenhall Glacier in Landsat image from 2014. Yellow arrows indicates 1984 terminus location and the purple dots the snowline.

Mendenhall Glacier in Landsat image from 2015. Yellow arrows indicates 1984 terminus location and the purple dots the snowline.

Mendenhall Glacier in Landsat image from 2017. Yellow arrows indicates 1984 terminus location and the purple dots the snowline.

Mendenhall Glacier in Landsat image from 2019. Yellow arrows indicates 1984 terminus location and the purple dots the snowline.