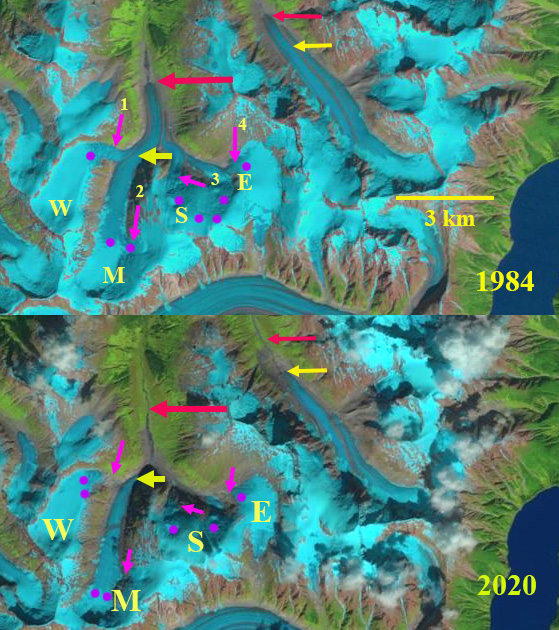

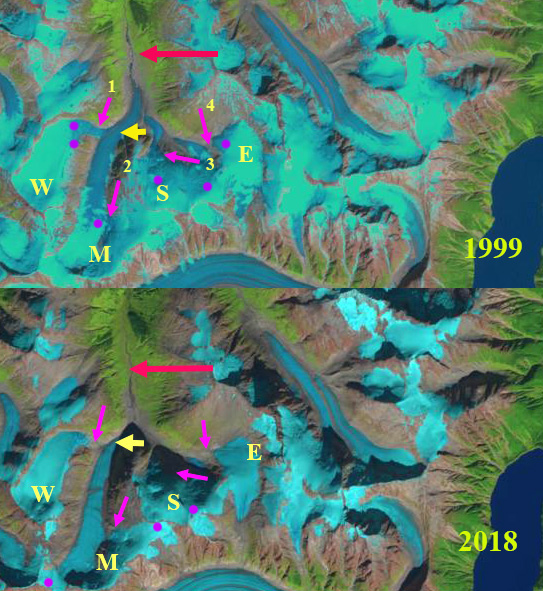

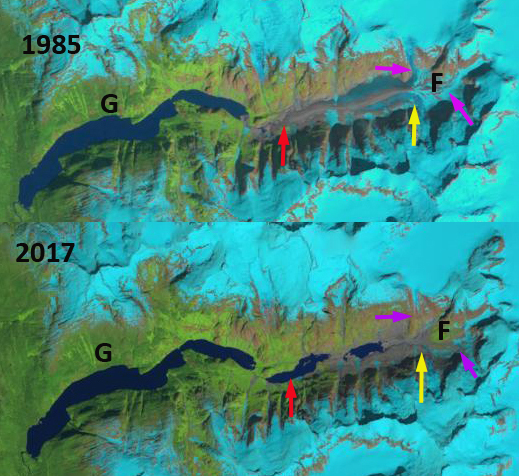

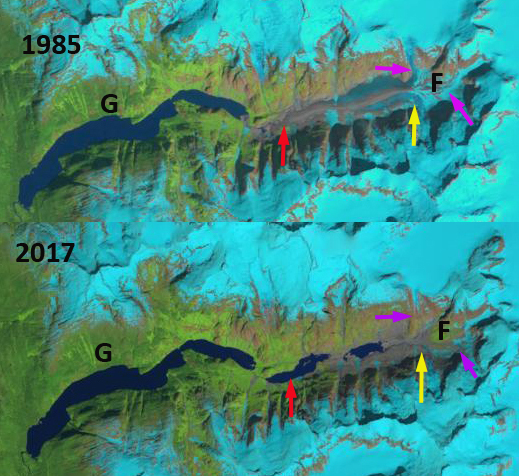

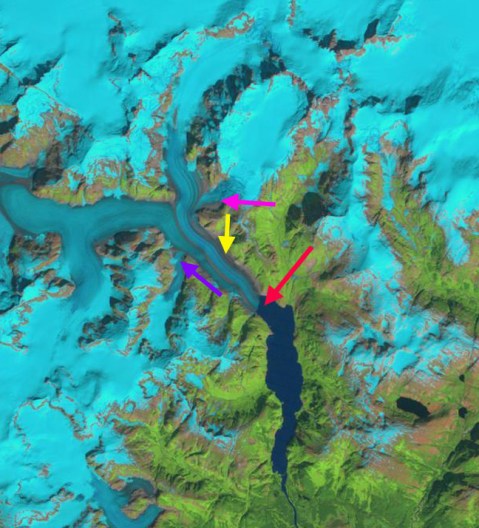

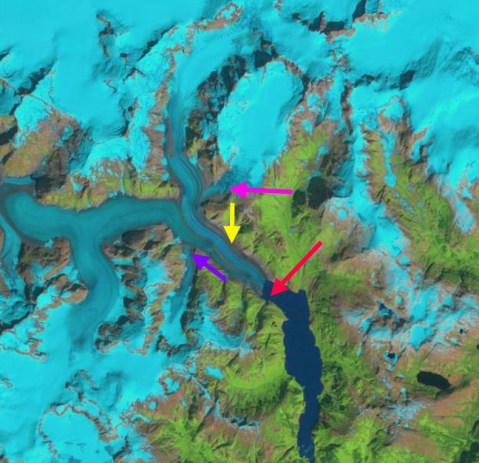

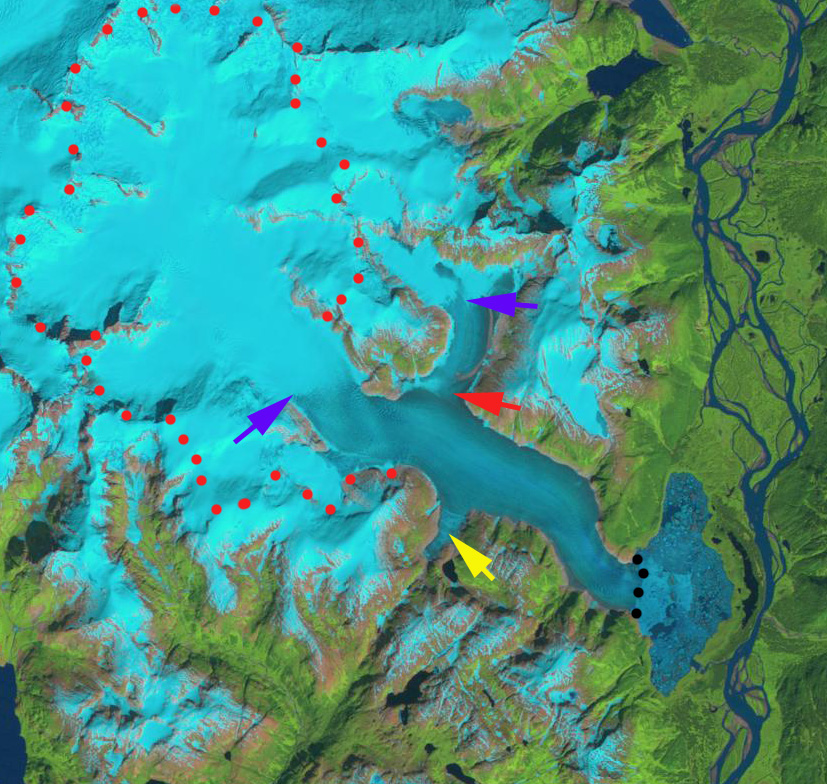

Dawes Glacier retreat in 1985 and 2020 Landsat images. Red arrow 1985 terminus, yellow arrow 2020 terminus. Point 1-3 are tributaries joining the main glacier. The glacier is about to separate into two calving termini.

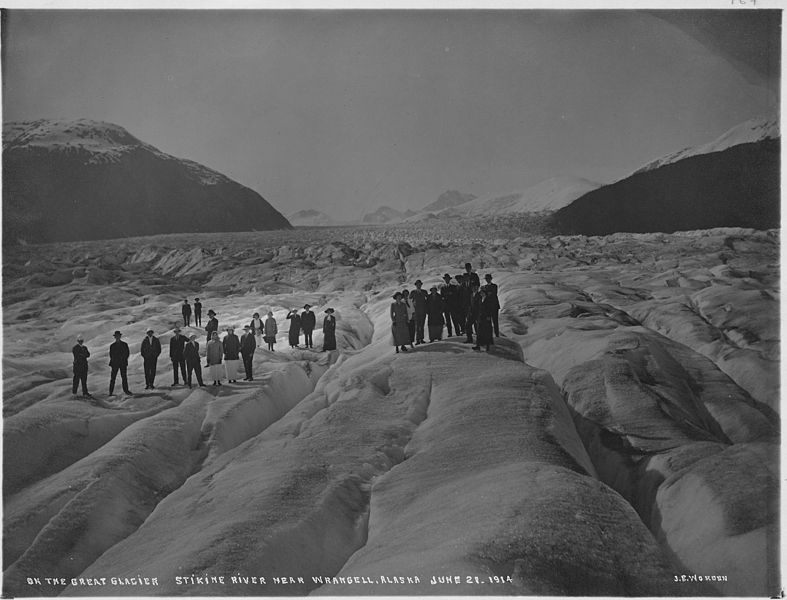

Dawes Glacier terminates at the head of Endicott Arm in the Tracy Arm-Fords Terror Wilderness of southeast Alaska. Endicott Arm is a fjord that has been extending with glacier retreat, and is now 58 km long. Dawes is a major outlet glacier of the rapidly thinning Stikine Icefield. Melkonian et al (2016) observed a rapid thinning of the Stikine Icefield of -0.57 m/year from 2000-2014. Here we compare Landsat imagery to identify changes from 1985-2020. Endicott Arm is host to a population of harbor seals that prefer hauling out on icebergs during the day supplied by Dawes Glacier (Blundell and Pendleton, 2015)

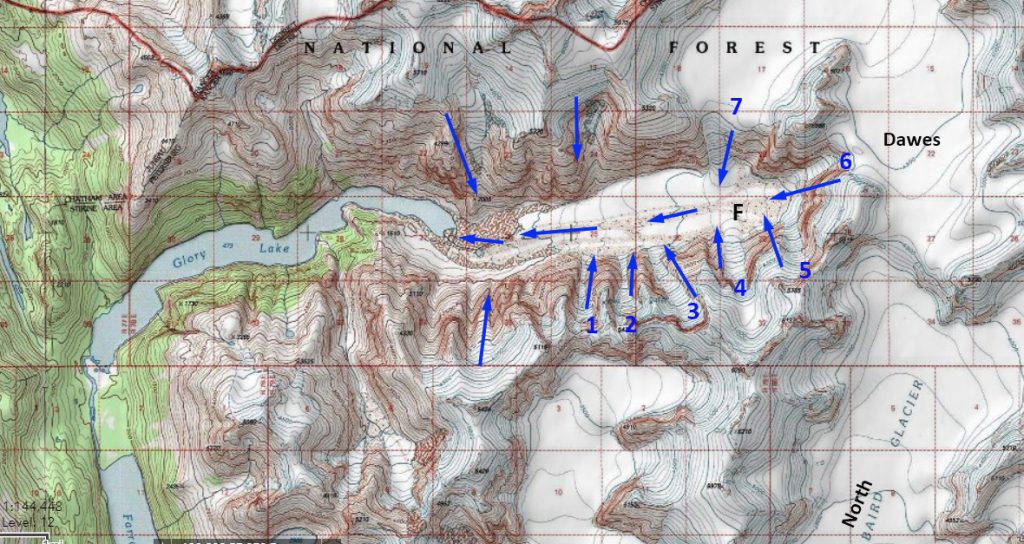

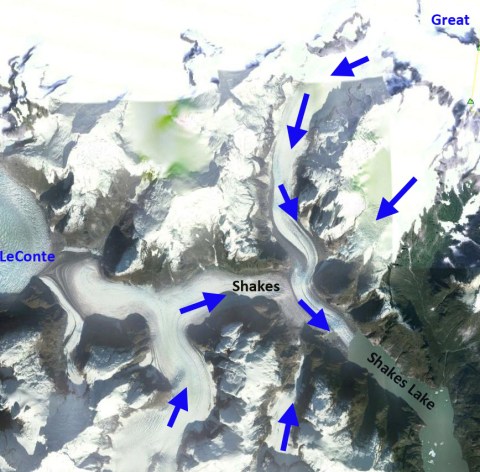

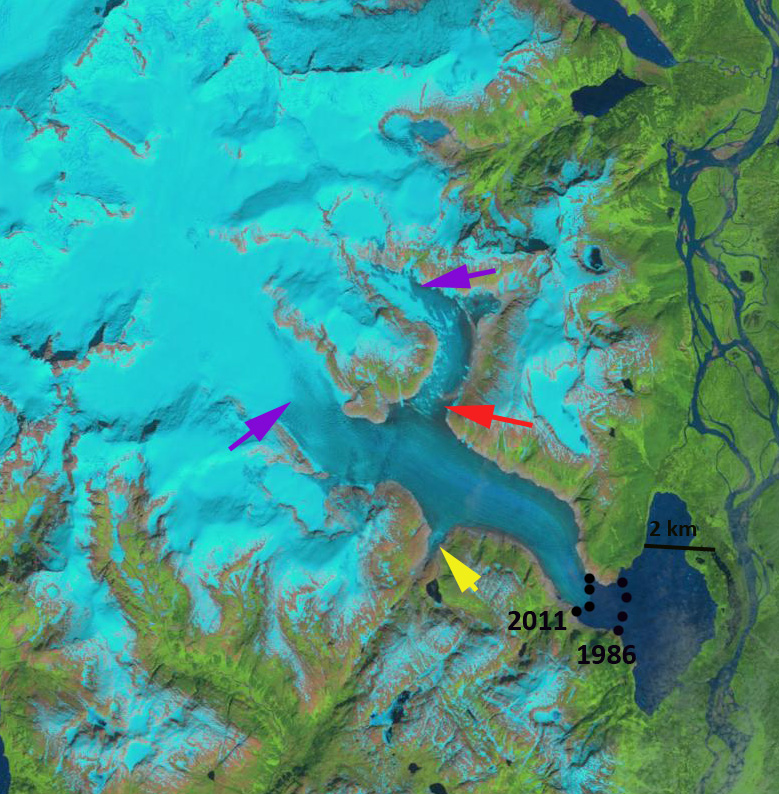

In 1985 the glacier terminated at the red arrow in each image, the tributaries at points 1,2 and 4 connected with the main glacier. Point 3 is the junction point of two tribuataries. The northern arm is 1.3 km wide and the eastern arm is 2.5 km wide. The snowline was at 1100 m. In 1987 the snowline on the glacier was at 1150 m. By 1999 the glacier had retreated 900 m since 1985 and the snowline was at 1300 m. In 2019 the tributaries at Point 1, 2 and 4 have detached from the the main glacier. At Point 3 the northern arm has declined to 0.7 km wide and the eastern arm is 1.8 km wide. In 2019 the snowline is at a record 1450-1500 m.This fragmentation of Dawes Glacier will continue, which leads to a reduced ice flux to the terminus reach. By 2020 Dawes Glacier has retreated 3.8 km since 1985, a rate of 105 m/year. The snowline is again exceptionally high at 1400-1450 m. Of equal importance the glacier terminus is separating into two individual calving termini, that could become fully separate this summer of 2021.

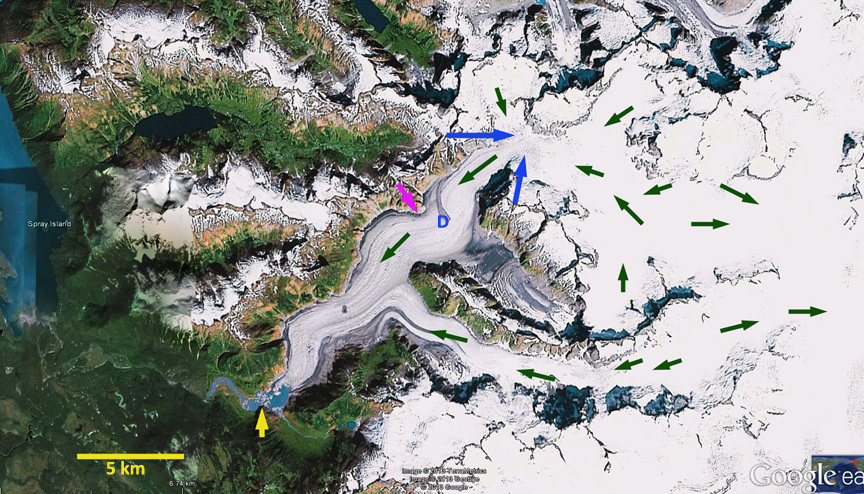

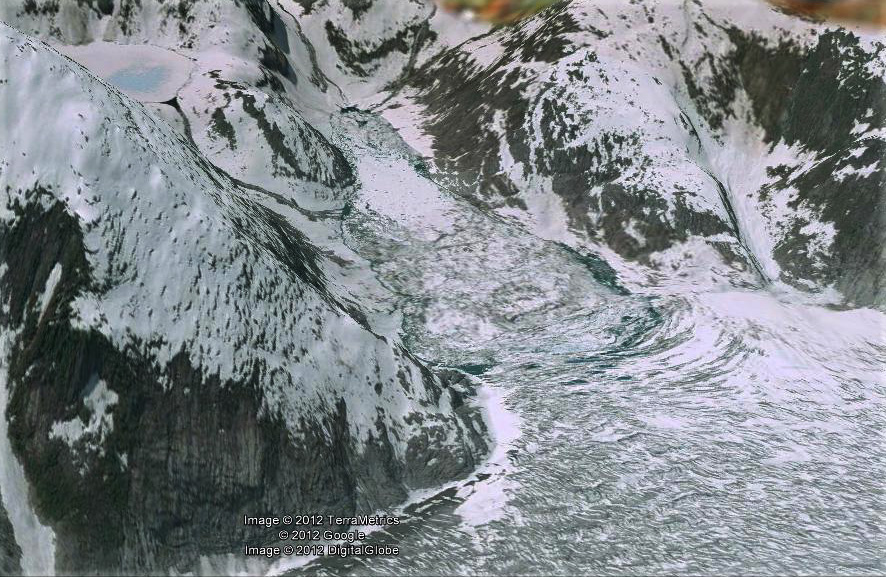

McNabb et al (2014) reported a thinning of 62 m/year from 1985-2013. The reduced inflow and up glacier thinning is ongoing and has driven the increased retreat rate despite a reduction in water depth at the cavling front. A key mechanism for retreat over the last century has been calving. The 2007 Hydrographic map of the area indicates water depth at the calving front still over 100 m, with a depth of 150 m 1 km down fjord of the terminus (see bottom image). The depth more recently has declined to 60 m at the calving front in 2013 (Melkonian et al 2016), yet retreat has increased driven by enhanced melting. The glacier thinning is continuing, but the retreat rate will decline as the fjord head is approached.

At the glacier front the velocity was 13 m/day in 1985, increasing to 18 m/day by 1999 and declining to 5 m/day by 2014 (Melkonian et al 2016).

This reduction will reduce calving and iceberg production. As icebergs are reduced harbor seals will be disappointed as they prefer icebergs to haul out on. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game has been monitoring harbor seals in the fjord and noting that females travel to pup on the icebergs in the spring and also utilize them for mating. ADFG attached satellite tags to harbor seals to monitor their movements beyond the breeding and puppin season finding that that adult and sub-adult seals captured in Endicott Arm spent the late summer and fall months in Stephens Passage, Frederick Sound, and Chatham Strait. How will a reduction in icebergs affect this population overall?

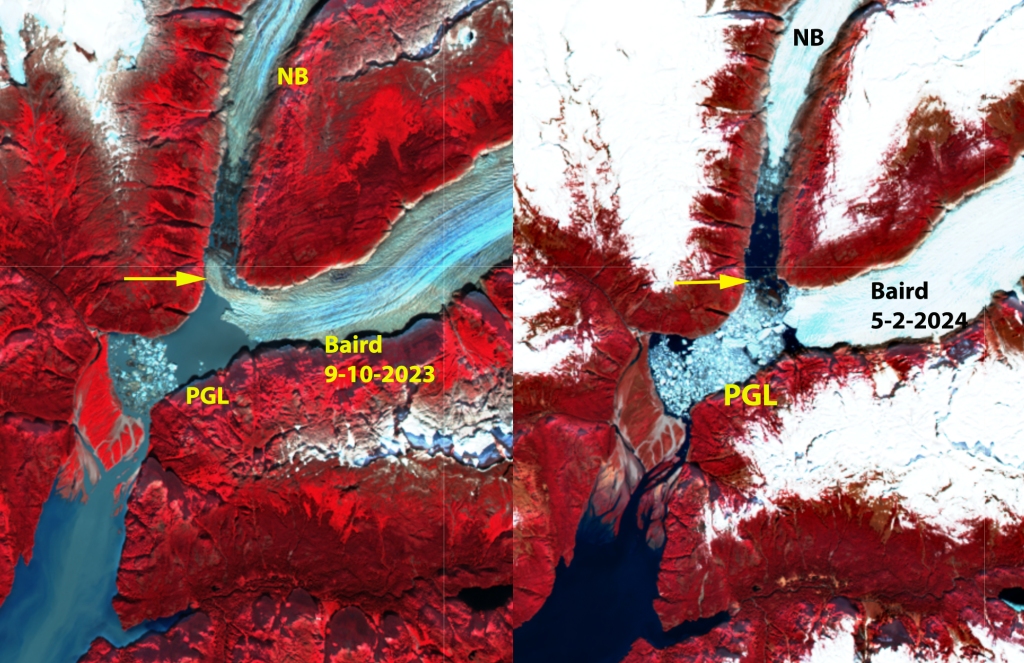

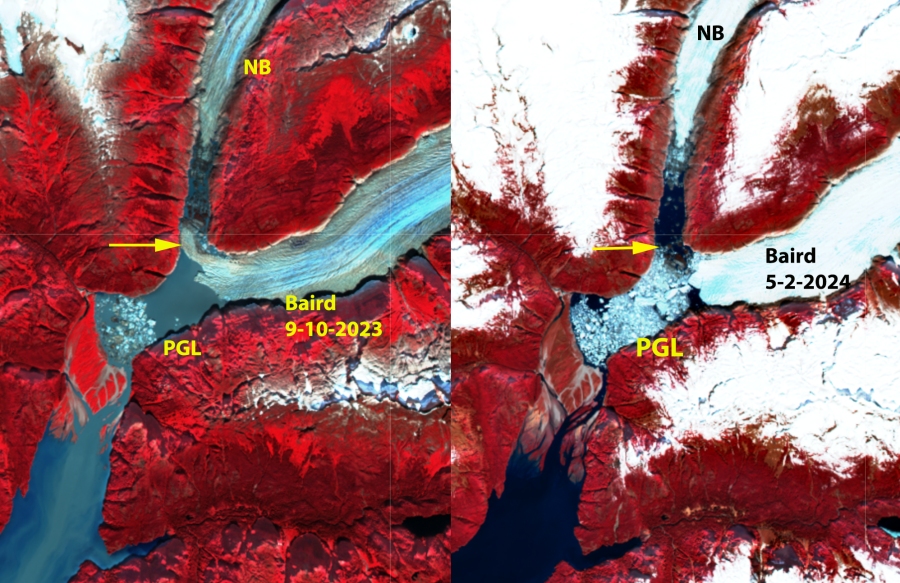

The retreat leading to separation is also happening at other outlets of Stikine Icefield such as Baird Glacier and Sawyer Glacier.

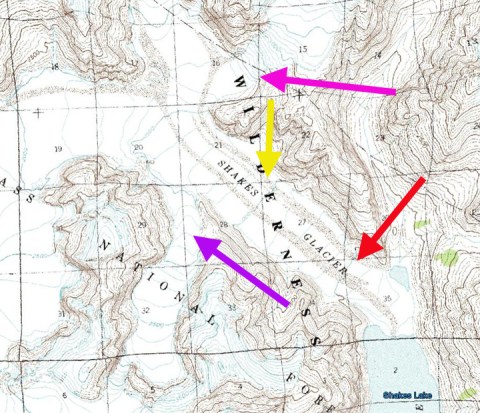

Dawes Glacier retreat in 1985 and 2020 Landsat images. Red arrow 1985 terminus, yellow arrow 2020 terminus and purple dots the snowline. Point 1-4 are tributaries joining the main glacier.

Dawes Glacier retreat in 1985 and 2020 Landsat images. Red arrow 1985 terminus, yellow arrow 2020 terminus and purple dots the snowline. Point 1-4 are tributaries joining the main glacier.

Dawes Glacier in June 2021 Sentinel image. Indicating the impending separation of the terminus.

Hydrograh of Endioctt Arm from 2007.