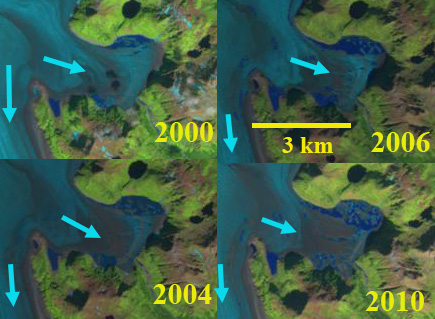

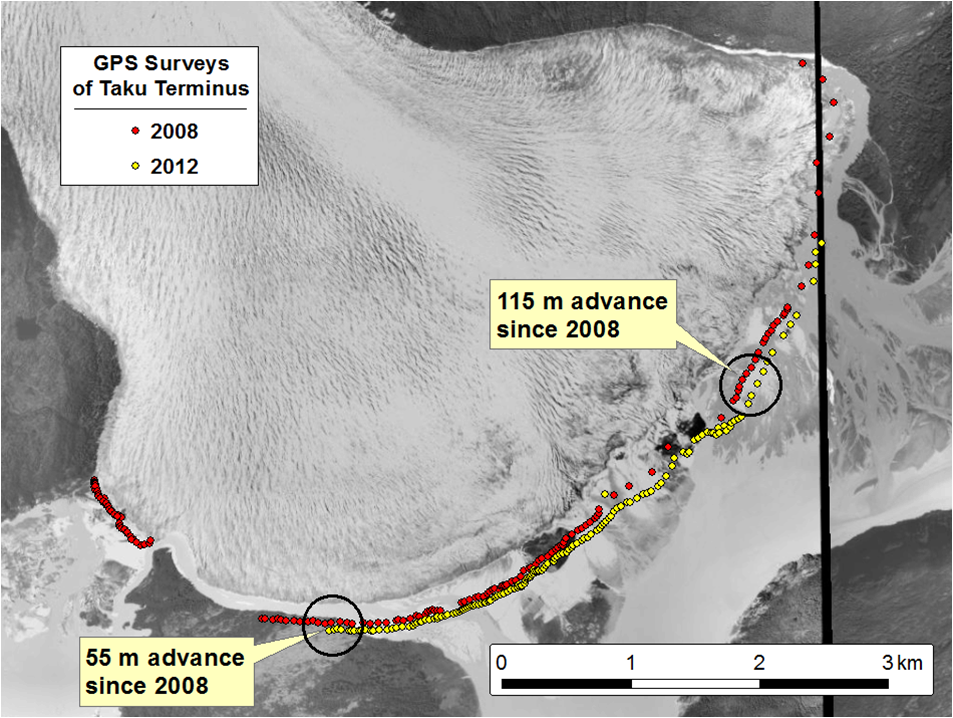

Ellsworth Glacier in Landsat images from 2018, 2019 and 2020. Red arrow is the 2016 terminus location, yellow arrow is the 2020 termins location, pink arrow is the rift, purple dots is the snowline, iceberg is Point A. Glacier retreated 2.4 km, main iceberg 1 km2

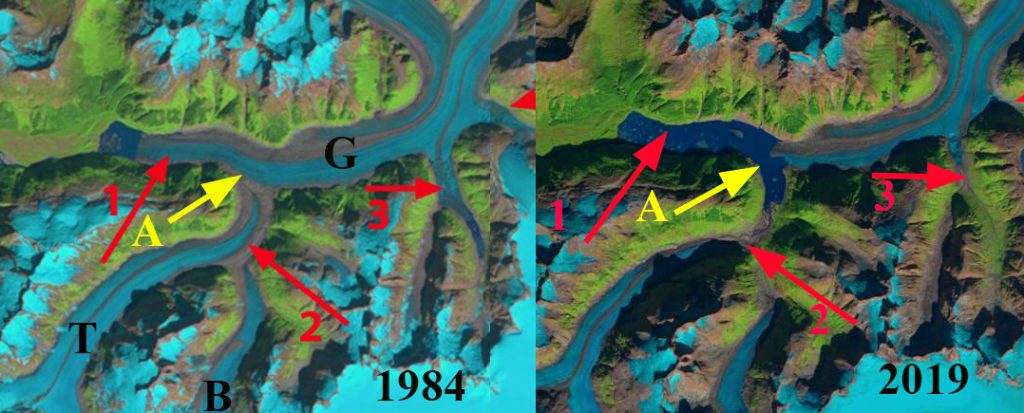

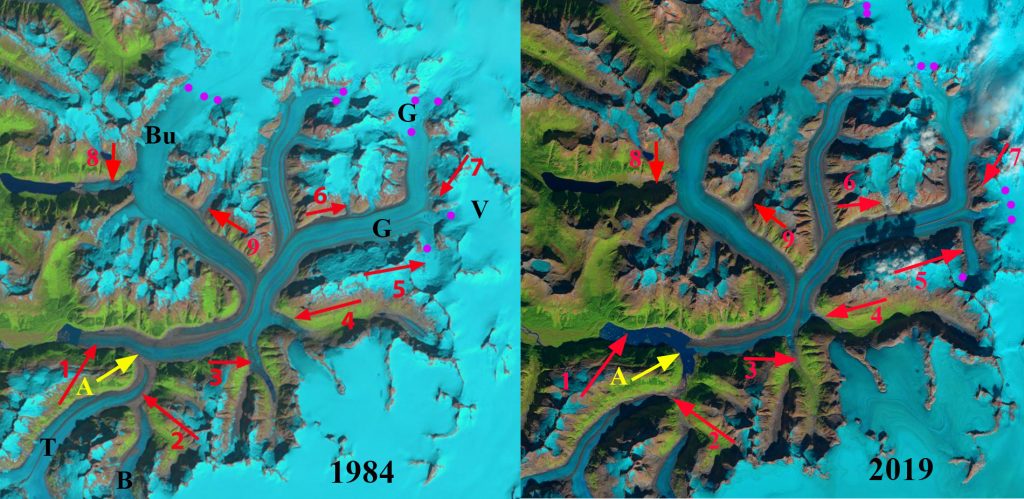

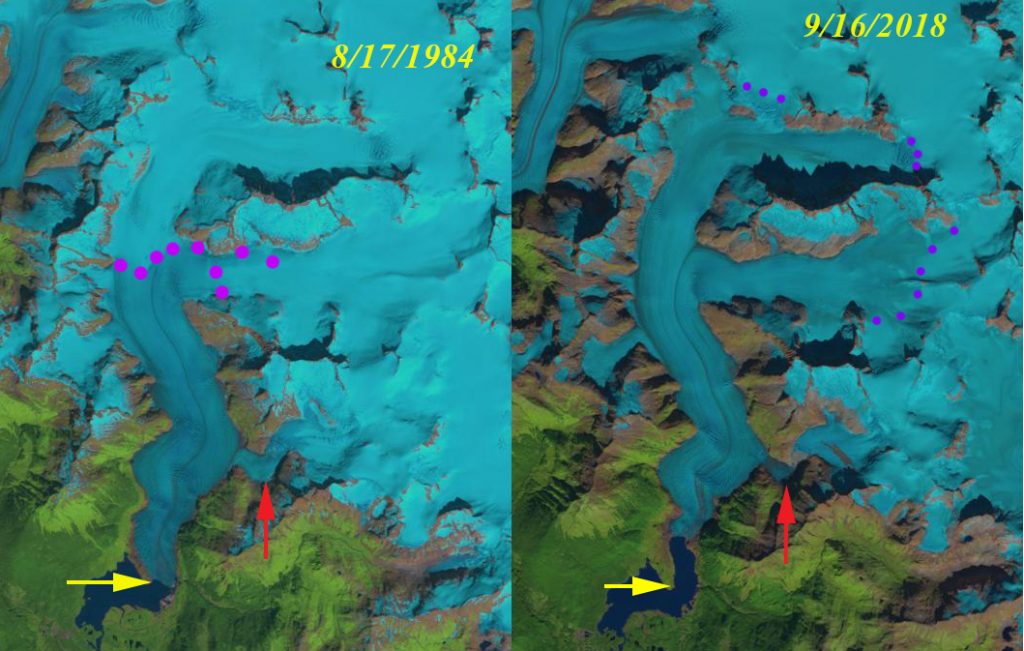

Ellsworth Glacier is a valley glacier draining south from Sargent Icefield on the Kenai Peninsula in Alaska. Along with the Excelsior Glacier it has been the longest glacier of the icefield. The glacier retreated into an expanding proglacial lake in the early 20th century (USGS-Molnia, 2008). The terminus in 2000 was reported to be 3.5 to 4.5 km from the 1908 position (USGS-Molnia, 2008). In a previous post we examined Landsat images from 1989-2016 to identify the changes including a 500 m retreat on the east margin of the lake and a 3400 m retreat on the west margin. It as noted that “this rapid lake expansion indicates that the lower 3 km of the glacier occupies a basin that will become a lake and that the tongue is partially afloat and given the narrowing thinning tongue is poised for collapse”. Here we document that collapse with Landsat images from 2016-2020.

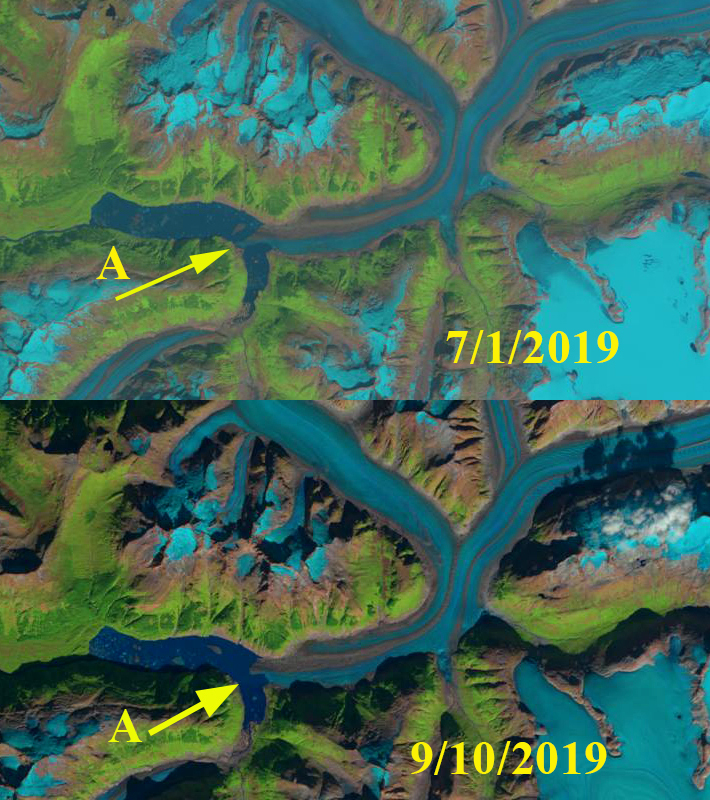

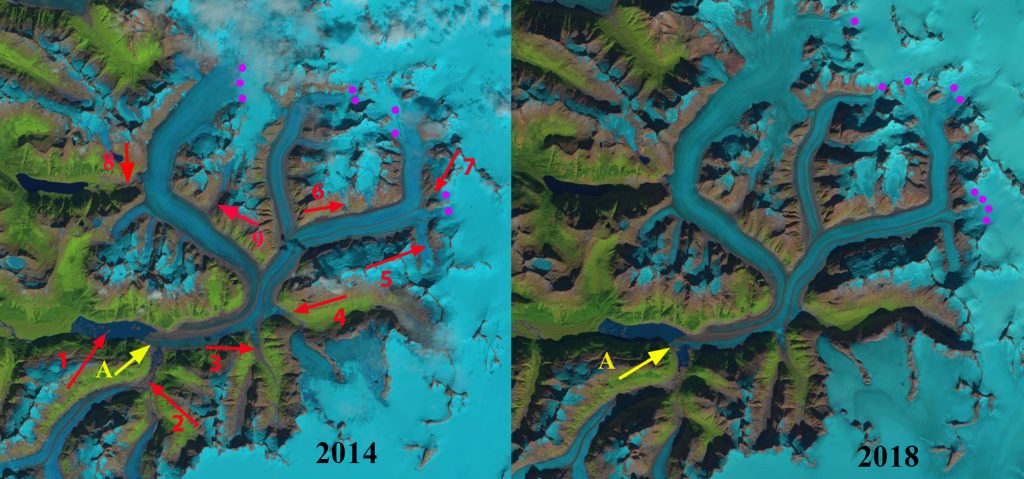

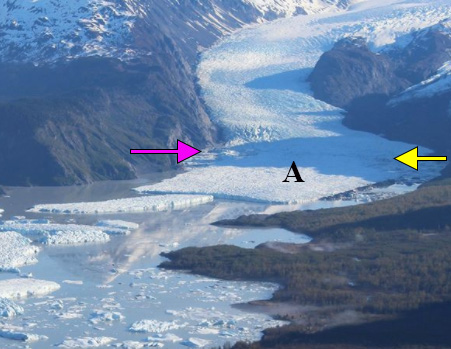

In 2016 the snowline is at 975 m, the lake has now extended 3 km along the western edge. The terminus is just east of a former tributary glacier, red arrow. The number of icebergs in 2016 indicates that significant ice calved during that year. The retreat of the eastern margin has been 500 m, with a 3.4 km retreat on the west margin. The main tongue in the lower two kilometers is 800 m wide versus 1200 m wide in 1989. In 2018 the snowline is at 1100 m, the terminus remains just west of a former tributary glacier. There is a rift forming near the pink arrow, where an iceberg will eventually detach (A). In late June of 2019 the rift has further developed, but the iceberg to be (A) has not detached. By mid-August of 2019 the rift has nearly led to detachment of an iceberg (A), the snowline is at 1075 m. In June of 2020 the iceberg has detached and there is a considerable melange of ice between the iceberg (A) and the main terminus. By Sept. 11, 2020 the iceberg remains in much the same position.

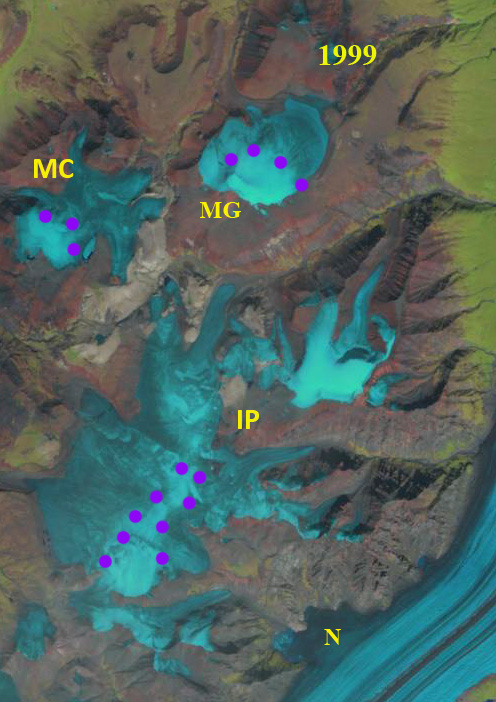

The glacier has retreated 2.4 km since 2018, and now terminates at yellow arrow 1 km downglacier of the junction of the two main tributaries. The iceberg has maintained an area of ~1 km2. The snowline in 2020 is at 1125 m indicating another of mass balance loss for the glacier. The lake is now 7 km long and the lake area is ~7.5 km2 up from 5 km2 in 2016. The retreat of this glacier paralells that of its neighbor Excelsior Glacier that retreated 4.7 km from 1994-2018. This continues to be a developing lake district including Grewingk Glacier.

Ellsworth Glacier in Landsat images from 2016-2020. Red arrow is the 2016 terminus location, yellow arrow is the 2020 termins location, pink arrow is the rift, purple dots is the snowline, iceberg is Point A.

Ellsworth Glacier in 2019. Point A is future iceberg is, yellow arrow is 2020 terminus locations and pink arrow is rift. Image from Johnstone Adventure Lodge.