Guest Post by Ben Pelto, PhD Candidate, UNBC Geography, pelto@unbc.ca

During the spring season we visited our four study glaciers (Figure 1), which form a transect of the Columbia Mountains from the Kokanee Glacier in the Selkirk Range to the south, to the Conrad (Purcells) and Nordic (Selkirks) in the center, to the Zillmer of the Premier Range in the north. This post will explore the snowpack of winter 2016 across the Columbia Basin of British Columbia. For a video of the work this spring see here.

Figure 1. Map of the Columbia watershed basin in Canada. Our four study glaciers are red stars, and other glaciers are teal, per the Randolph Glacier Inventory. Major rivers and lakes are blue.

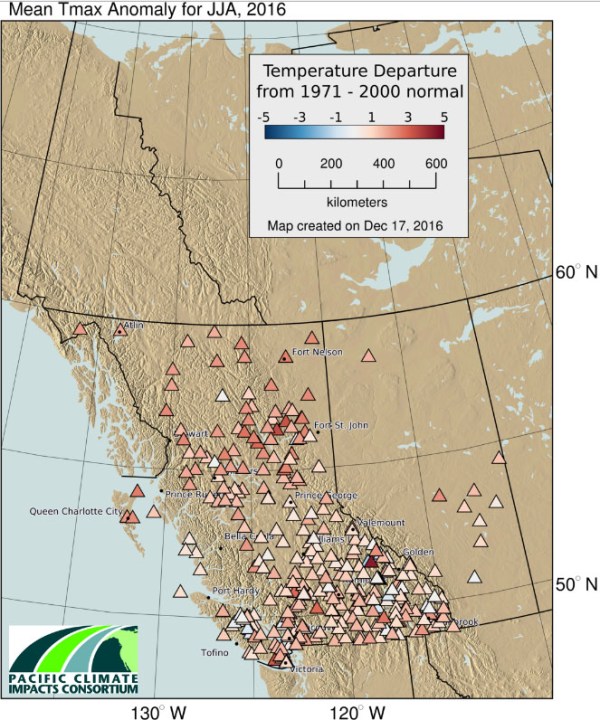

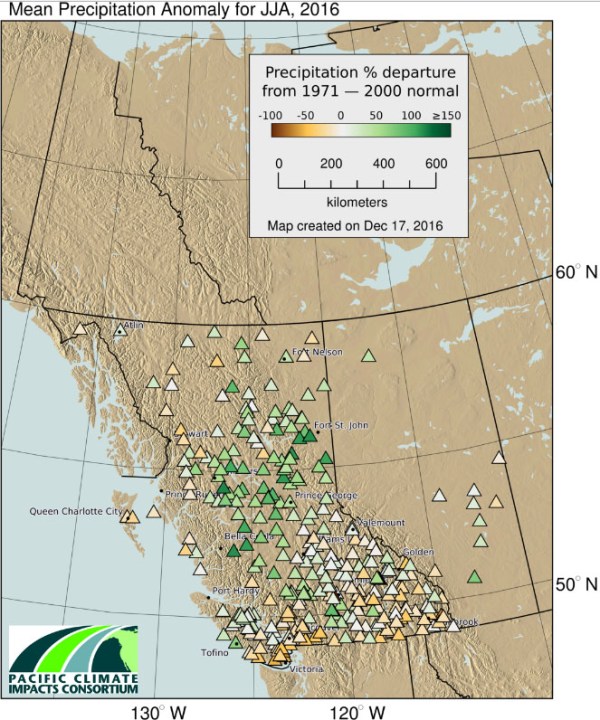

Winter 2015-2016 Snowpack Summary: Early winter, September-December, 2015 brought a number of Pacific storms, in contrast to 2013 and 2014 which featured few storms and relatively dry conditions. By January 1st, snowpack across the province was near-normal, though a strong north-south gradient was observed, with above average snowpack in the south, average snowpack in central BC and well below average snowpack in the north (provincial snowpack was below normal Jan. 1st, 2015; BC River Forecast Centre). February was warm and wet, with daily temperatures 1 to 5˚C above normal. By the beginning of March, snowpack was below average over most of the province north of Prince George and Bella Coola and near or above average to the south.

Snow continued to accumulate in March, but primarily at higher elevations due to above average freezing level heights. The height of freezing levels determines whether precipitation falls as snow or rain at a given elevation. Figure 2 shows that median freezing level height is 600 m above sea level for February at the Conrad Glacier, yet this February featured an average freezing level of 1300 m. This means that on average, in the month of February, snow fell above 1300 m and rain below 1300 m (of course this is an average and any one storm may be different). Most glaciers in the Columbia Mountains are located above 2000 m elevation, and in the winter of 2014-2015, freezing levels were often near or above the height of many of the peaks in the Columbia Mountains (3000 m), allowing for rain on snow events. Such events were reportedly rare in 2015-2016 winter until April/May, despite the fact that freezing level heights were record high for December-April (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Estimated freezing level height (elevation of 0˚C) for the Conrad Glacier from June 2015-May 2016. Note that February-April 2016 were at or above the 95th percentile, meaning that there is less than a 5% chance that the freezing level heights will be that high given the data from 1948-2016 from which the median height is derived. Freezing levels are estimated from NCEP/NCAR Global Reanalysis data determined every six hours from 1948-present (North American Freezing Level Tracker).

Figure 3. Estimated mean freezing level height (elevation of 0˚C) for December-April from 1948-present for the Conrad Glacier (North American Freezing Level Tracker). Note that 2016 is the year of record. Freezing levels are estimated from NCEP/NCAR Global Reanalysis data determined every six hours from 1948-present.

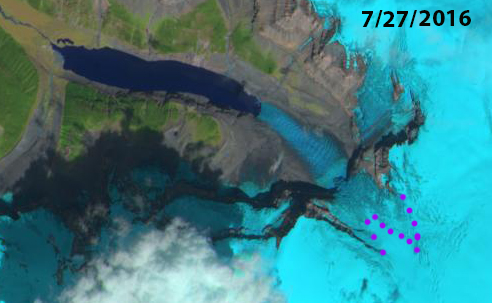

Warm temperatures experienced in February continued through March and April across the province. By April 1st, provincial snowpack was near-normal at 91% of average (Figure 4). The north-south gradient in snowpack grew, with the southern half of the province at or above average, and the northern half below average. Typically, May 1st marks the peak of snow accumulation, and the melt season ensues. In 2015, the melt season began in mid-April, 1-3 weeks early. The 2016 melt season began earlier still, coming in late March/early April, 4-6 weeks early. Figure 5 shows that for the East Creek snow pillow near the Conrad Glacier, snowpack peaked in late March at around 120% of normal. Early maximum snow depth occurred due to a combination of dry, warm conditions. Typically, small precipitation events continue to add snow to alpine environments through April, and by swapping precipitation for dry, warm conditions, the snowpack began to decline in earnest in late March/early April.

Figure 4. British Columbia Snow Survey Map for April 1st, 2016 (BC River Forecast Centre). Note that snowpack is roughly average in the south and 50-75% of average to the north.

Figure 5. Automated snow pillow data showing snow water equivalent (SWE, amount of water obtained if all the snow were to be melted per unit area) for East Creek, near the Conrad Glacier at 2004 m elevation. Note that peak SWE was 4-6 weeks early, but was around 120% of normal at the time, followed by rapid melting (BC River Forecast Centre).

By May 15th, provincial snowpack was 39% of normal (Figure 6), a rapid decline from near average mid-winter snowpack. The north-south gradient also largely disappeared, though the three basins doing the best were the North and South Thompson, and the Upper Columbia at 70-86% of normal. Interestingly the Upper Columbia contains three of our four study glaciers. The May 15th provincial average of 39% is a new record low (measured since 1980, BC River Forecast Centre). May 15th snowpack is more typical of mid-June, indicating that snow melt is about four weeks ahead of normal. Most rivers are past the spring freshet, and discharge has begun to recede. The early freshet will put pressure on summer low flows across the province in snow-melt dominated rivers.

Figure 6. British Columbia Snow Survey Map for May 15th, 2016 (BC River Forecast Centre). Note that snowpack that was roughly average in the south as of April 1st is now well below average, and 50-75% of average to the north.

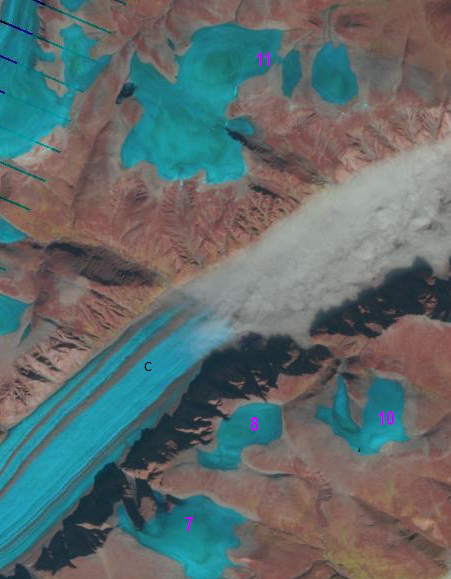

Field Work Overview—What we do: The primary goal of the spring field season is to determine how much snow fell over the winter on the four study glaciers. To do so, we take snow depth measurements using a heavy-duty avalanche probe. Snow depth is valuable information, but snow water equivalent (SWE; if you melted the snow in a given location, this would be the depth of water left behind per unit area) is the key to understanding how much water the snow contains. As you can imagine, a meter of powdery snow may contain only 10 cm of water, whereas a meter of wet snow may contain 30 cm of water. To measure density, we either take a snow core (think a tube of snow…like an ice core, except snow instead) and cut samples to weigh, or we dig a snow pit and then take samples from a wall in the snow pit. By combining measurements of density and depth, we are able to calculate SWE over the entire glacier. A typical end of winter SWE for a Columbia Basin glacier would be around 2 meters water equivalent, which would be roughly 4.5 meters of snow. By knowing how much snow covers the glacier, we know how much mass the glacier gained during the winter. At the end of the summer, we visit the glaciers again, and we measure how much melt occurred. By combining the winter accumulation of snow, and summer melt of snow and ice, we can determine how much the glacier gained or lost during the year. Figure 7 is an illustration of the product of depth and density measurements, and displays the relationship of elevation and accumulation over the Conrad Glacier. To see what we do watch: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wWYJdQnRq5k

Figure 7. Winter balance gradient for the Conrad Glacier in millimeters water equivalent per meter of elevation. Snow depth increases with elevation linearly, except in topographically complex areas, and nearest the top of the glacier (3200 m). Most of the glacier area is between 2000-3000 m.

We also are flying LiDAR surveys of our study glaciers. LiDAR is a laser sensor mounted on the bottom of an aircraft. The LiDAR unit essentially shoots rapid laser pulses, each pulse hits the surface and returns to the sensor. The time it takes for the signal to travel to the surface and back tells us the distance from the plane to the ground. With this data, we can make a detailed 3-D map of the glacier surface. This map is accurate to 10-25 cm in the vertical, and 50 cm laterally. By collecting this data biannually (spring and fall) we can determine how much snow fell, or melt occurred by subtracting subsequent 3-D maps from one another (e.g. by subtracting a September map from an April map of the same year, we can determine how much melt happened between the two flights). This data offers the ability to be able to cover far larger areas than is feasible for fieldwork.

By comparing our field data with the LiDAR data, we can determine whether the LiDAR is capturing the reality on the ground, and if the field data is able to represent spatial variability in snow depth. Our LiDAR flights occur over a day or two, whereas our field data are collected over a month. In order to directly compare both, we conduct a GPS survey of the glacier surface along the center of the glacier. We then compare the difference in elevation between the survey and the LiDAR and thus can account for any melt or accumulation that occurred in the intervening days or weeks.

This spring we also collected data using a Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) which transmits high-frequency radio waves into the ice. When the radio waves encounter a buried object or a boundary between materials, then it is reflected back to the surface where a receiving antenna records the signal. In our case, the bedrock surface below the ice is the surface/boundary we are looking for. Once we pick out the bedrock surface from the data, then the signal and travel time are used to then determine the ice thickness (Figure 8). Ice thickness is important for determining how long a glacier will survive as well as putting current rates of ice loss in perspective. We still have a lot of data to collect and process, but it seems that smaller glaciers like the Nordic and Zillmer (~5 km2) are 50-90 m thick in general, larger glaciers like the Conrad (16 km2) average 100-200 m thick.

Figure 8. Ground Penetrating Radar data from the Conrad Glacier. The blue line marks the bedrock surface and the red line marks the airwave, which defines the glacier surface. Between the lines is glacier ice. The longer the signal travel time, the deeper the ice. For this line, the deepest point is 220 m ice depth, and the shallowest 115 m.

Field Season Stats:

- Snow Depth Measurements: 161 discrete locations, 600+ individual measurements

- Snow Pits and Cores (Density): 15

- The combination of snow depth and density allow for calculation of SWE

- Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) Distance (Ice thickness, Figure 3): Roughly 75 km

- GPR data allows for the calculation of ice thickness and ice volume

- Distance Skied: 200+ km

- Field Team Members: 8; UNBC, CBT, UBC, ACMG.

- Glaciers with both field and LiDAR data: 4/4

- GPS Surveys (to corroborate field/LiDAR data comparison): 4

- Days on a Glacier: 18

Season Summary: Our data indicate that winter mass balance featured a north-south trend, with the Kokanee Glacier in the south equaling last year’s mass balance, the central region was 85% of 2015 (Conrad and Nordic), and the Zillmer in the north was around 80%. The 4-6 week head start on melt season led to higher snow density in 2016 than observed in 2015. This summer melt season will determine whether the record/near record negative mass balance seen across the region in 2015 will be rivaled or exceeded in 2016. The hot, early spring has primed the region to again break records.