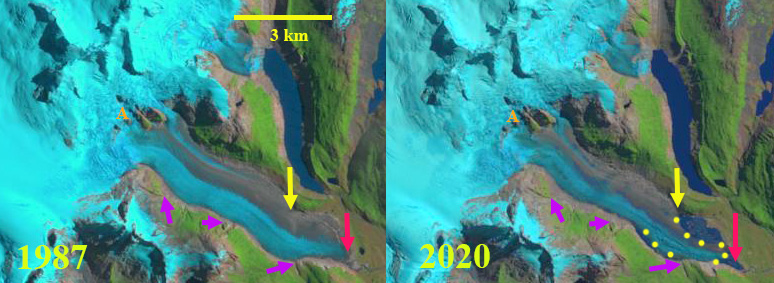

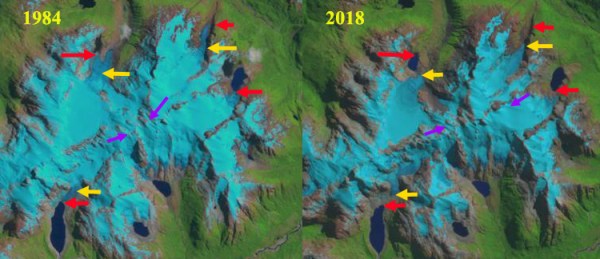

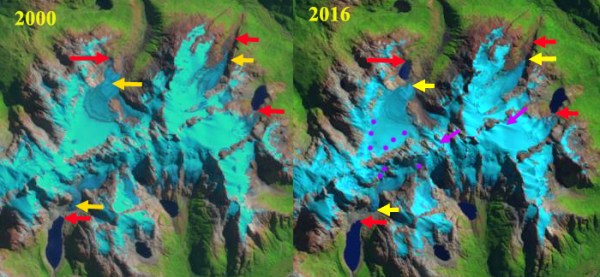

Soler Glacier in 1987 and 2020 Landsat images. Red arrow indicates 1987 terminus location, yellow arrow indicates 2020 terminus location on north side of glacier. Yellow dots indicate margin of lake and purple arrows indicate specific locations where glacier thinning is evident.

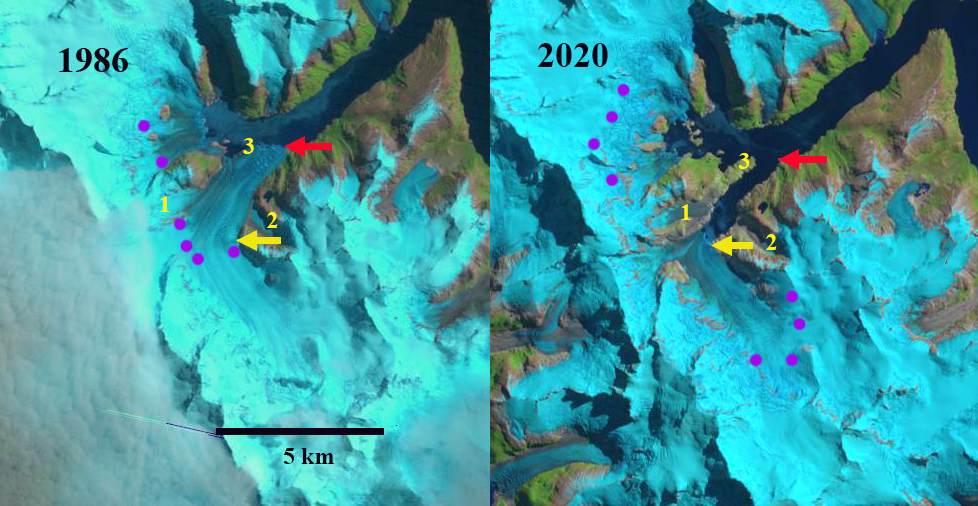

Soler Glacier is an outlet glacier on the east side of the Northern Patagonia Icefield (NPI). The terminus response of this glacier has been slower and more limited than on most NPI glaciers. Aniya and Fujita (1986) reported a total retreat of 200-350 m from 1944 to 1984. Glasser et al (2016) note the recent 100 m rise in snowline elevations for the NPI, which along with landslide transport explains the large increase in debris cover since 1987 on NPI from 168 km2 to 306 km2 . Loriaux and Casassa (2013) examined the expansion of lakes on the Northern Patagonia Ice Cap reporting that from 1945 to 2011 lake area expanded 65%, 66 km2. For Soler Glacier lake formation did not occur until the last decade and debris cover has changed little as well. Willis et al, (2012) identified thinning of ~2 m/year in the ablation zone from 1987-2011. This thinning is now leading to the development of a significant proglacial lake that is examined using Landsat images from 1987-2020.

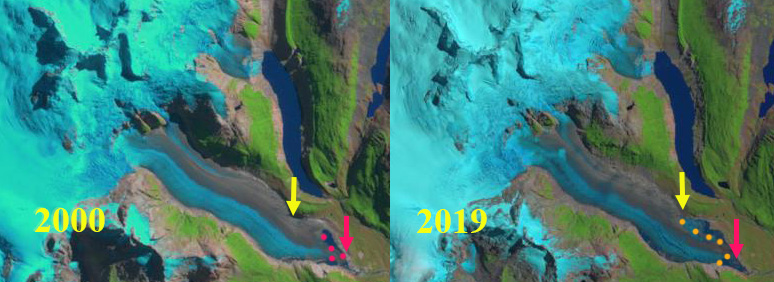

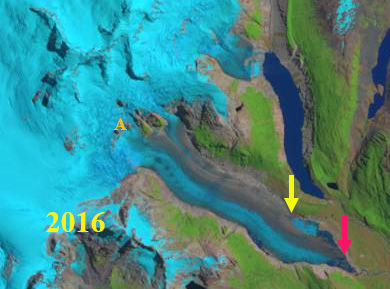

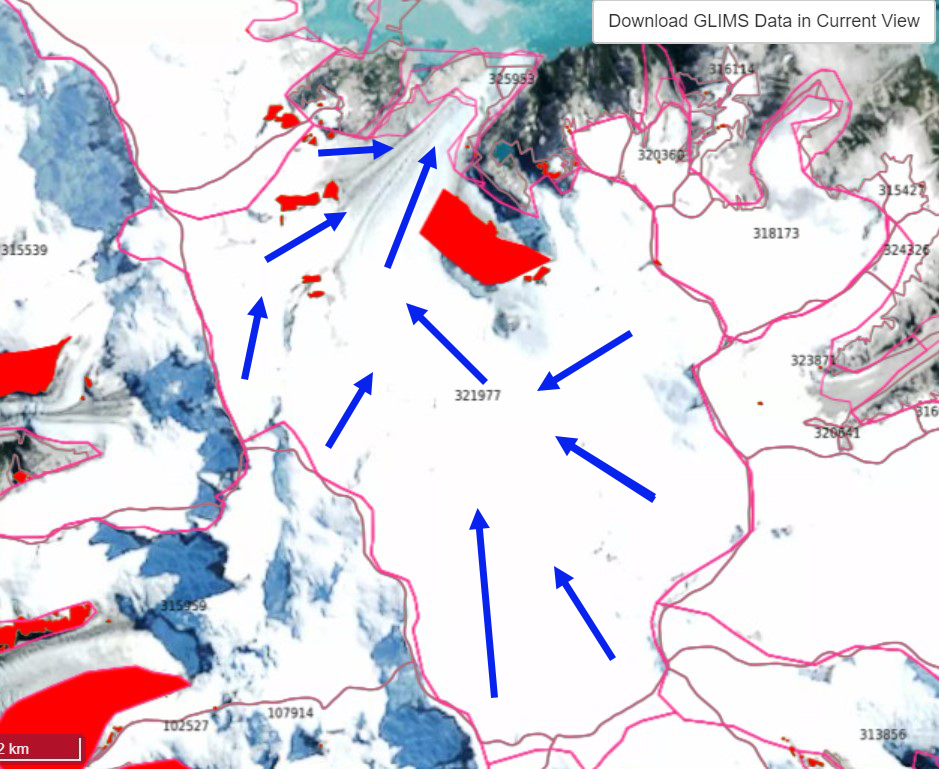

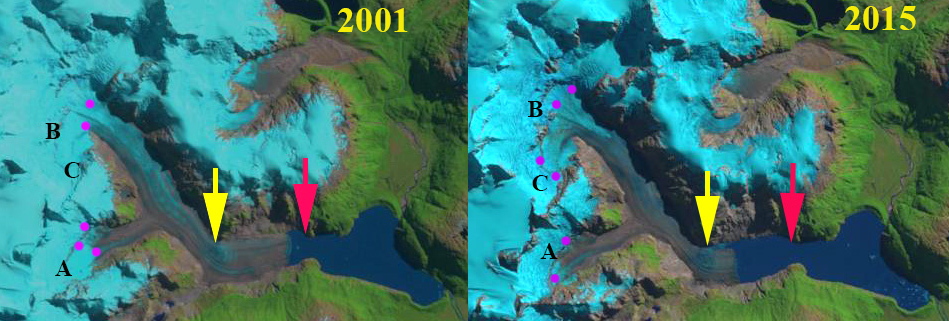

In 1987 the glacier is still up against the Little Ice Age moraine, though it had thinned considerably resulting in retreat down the slope of this vast moraine. By 2000 a small lake had developed both on the north and south side of the main terminus with a total area of ~0.3 km2, red dots. In 2016 and 2019 this lake had expanded, with the northern arm mostly filled with ice, orange dots. In October 2020 the lake has an area of ~1 km2 and is mostly open water. The extensive thinning of the terminus tongue continues to drive both retreat and lake expansion. The thining is evident at Point A where bedrock knobs have emerged from the ice near the snowline. The three purple arrows on the south side of the glacier indicate thinning as these bedrock features are increasingly distant from the glacier. The terminus has retreated 500 m in the glacier center, 2100 m on the north side and 1300 m on the south side from 1987-2020. The terminus tongue in its lowest 1.5 km continue to thin and will collapse in the lake in the near future. The end of summer snowline has averaged 1450 m in recent years leading to continued mass loss without calving in the lake (Glasser et al 2016).

Lake development here lags that of other glacier around the NPI such as Exploradores, Nef, Steffen and San Quintin.

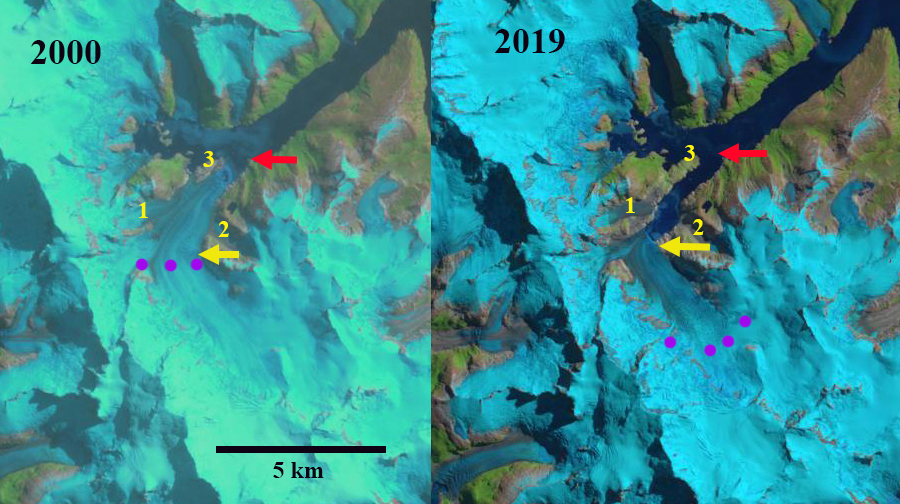

Soler Glacier in 2000 and 2019 Landsat images. Red arrow indicates 1987 terminus location, yellow arrow indicates 2020 terminus location on north side of glacier. Red dots and orange dots indicate margin of lake.

Soler Glacier in 2016 Landsat image. Red arrow indicates 1987 terminus location, yellow arrow indicates 2020 terminus location on north side of glacier.