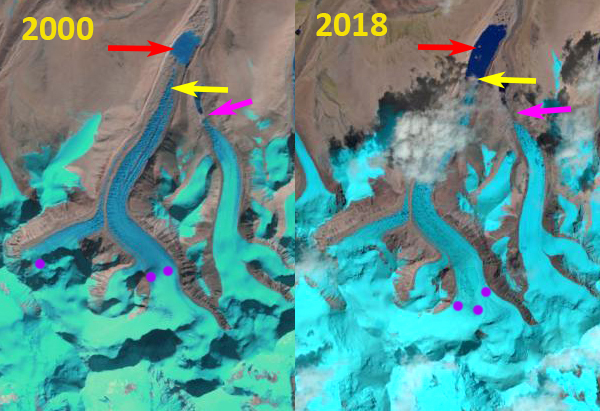

Duiya Glacier, China in 1990 and 2017 Landsat images. Red arrow indicates 1990 terminus, yellow arrow the 2017 terminus, pink arrow the terminus area of Duosangpuxi purple dots the snowline

Duiya Glacier, China is in the Pumqu Basin northwest of Mount Everest. The glacier terminates in an expanding lake. King et al (2018) report the proglacial lake is dammed by a full moraine loop, and the glacier loses mass via calving as and surface melt. Here we use Landsat imagery to identify changes from 1990-2018. The Pumqu River becomes the Arun River in Nepal , which has a proposed 900 MW hydropower plant under development .

In 1990 the glacier terminated in a small proglacial lake, 500 m across at 5500 m. The snowline in 1990 was at 6000 m. The Duosangpuxi Glacier to the east also terminates in a proglacial lake. In 2000 the lake has expanded to 800 m in length due to retreat. The glacier snowline is at 6000 m again. The Duosangpuxi Glacier to the east has retreated from the lake it formerly terminated in. By 2017 the glacier had retreated 1020 m a rate of 37 m/year. The lake is now over 1.5 km long. The snowline in 2017 is at 6200 m. In September 2018 the snowline has likely not reached its highest elevation but is just below 6200 m. The terminus is obscured by clouds, but has not changed significantly from 2017. There icebergs in the lake indicating calving continues. The high snowline in recent years indicate continued mass loss that will drive further retreat.

King et al (2017) examined the mass balance of 32 glaciers in the Everest region for the 2000-2015 period including the Duiya and found a mass loss of ~0.5 m/year, with the loss of lake terminating glaciers at ~-0.7 m/year. The retreat of this glacier is like that of Yanong Glacier and Chaxiqudong Glacier whereas Rongbuk Glacier has experienced supraglacial lake expansion, and thinning without as much retreat.

Duiya Glacier, China in 2000 and 2018 Landsat images. Red arrow indicates 1990 terminus, yellow arrow the 2017 terminus, pink arrow the terminus area of Duosangpuxi purple dots the snowline.

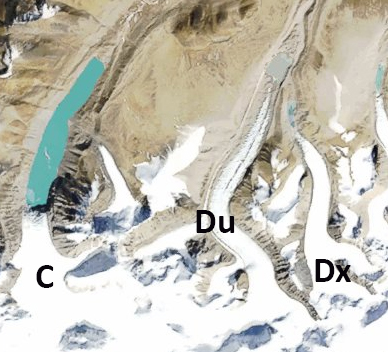

Broader view of the Duiya Glacier (Du) and neighboring glaciers Cuolangma (C) and Duosangpuxi (Dx), each terminating in a lake in 1990.