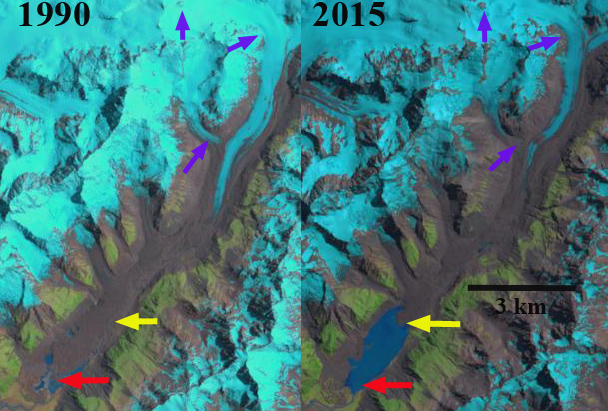

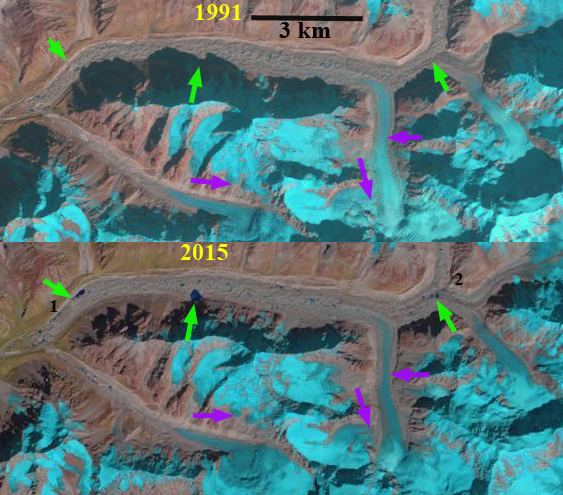

Comparison of four outlet glaciers of Sierra de Sangra in Argentina in a 1985 and 2015 Landsat image. Read arrow is the 1986 terminus location when all terminated in a lake. By 2015 only one terminates in a lake, yellow arrows.

The Sierra de Sangra Range is located along the Chile-Argentina boundary with the east draining glaciers flowing into the Rio Mayer and then into Lake O’Higgins at Villa O’Higgins. Here we examine four glaciers that in 1986 all ended in lakes and by 2015 only one still terminates in the lake. Davies and Glasser (2012) noted the fastest retreat rate of this icefield during the 1870-2011 period has been from 2001-2011. NASA’s Earth Observatory posted an article on this blog post with better resolution images.

Sierra de Sangra is just east of Villa O’Higgins with the crest of the range on the Chile Argentina border. The four glaciers examined here are indicated by S, SE, E and N.

The South Outlet Galcier (S) has retreated 700 m from 1986 to 2015 and terminated in a lake in 1986. By 2015 it terminates on a steep slope well above the lake. The Southeast Outlet Glacier (SE) terminates in a lake in 1986. By 2015 it has retreated 1200 m to a junction with a tributary from the north. The East Outlet Glacier is the largest glacier and has retreated just 300 m from 1986 to 2015. There is a sharp elevation rise 200 m behind the terminus, which likely marks the end of the lake basin. This is marked by a crevasse zone. The North Outlet Glacier (N) ended in a lake in 1986. By 2015 it has retreated 700 m and ends on a bedrock slope well above the former lake level. All of the glaciers have an accumulation zone in each satellite image examined. This indicates they can survive present climate. The glacier retreat is not as large as Cortaderal Glacier and Glaciar Del Humo.

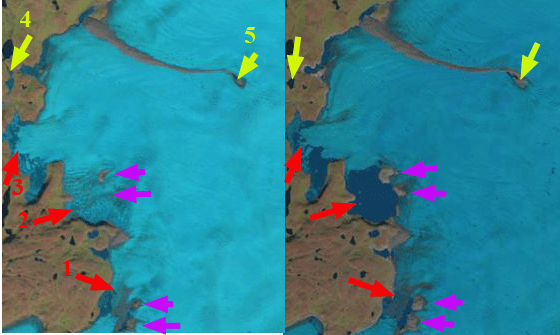

Google Earth images from 2013 of the terminus of three outlet glaciers above and one below. The red arrow indicates terminus location. Three of the four no longer terminate in a lake.