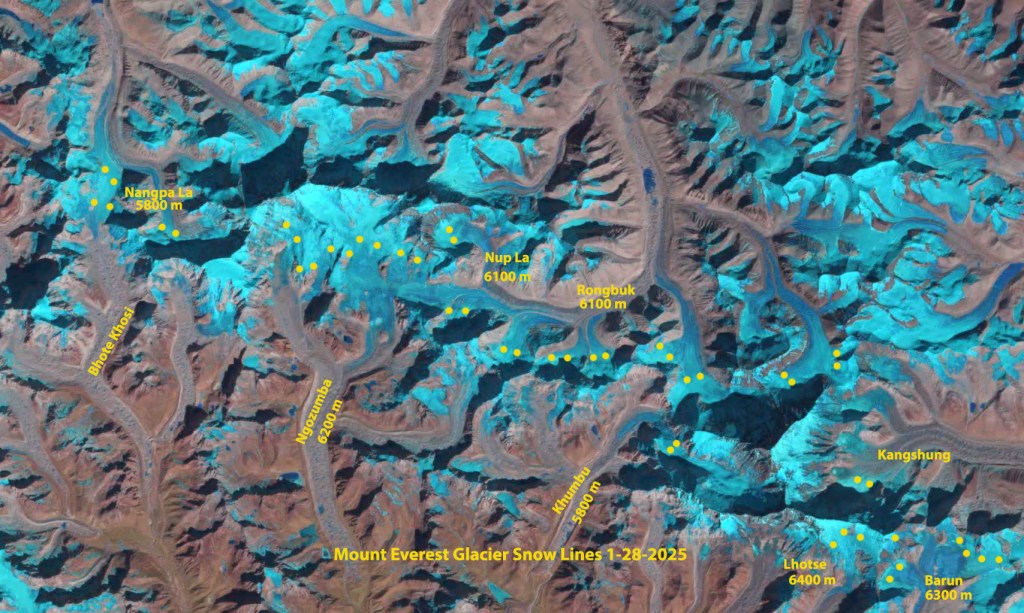

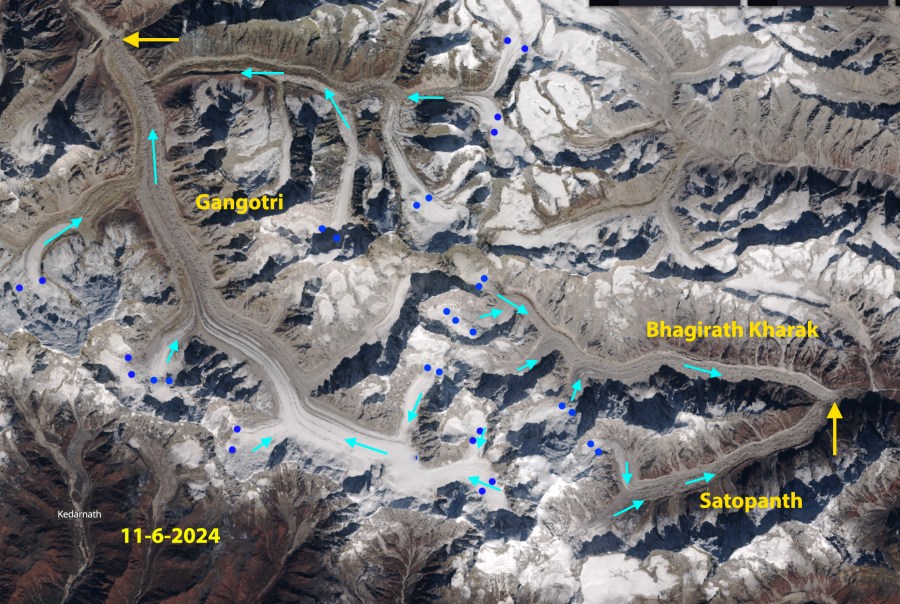

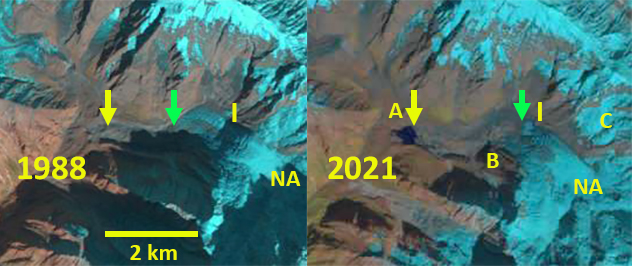

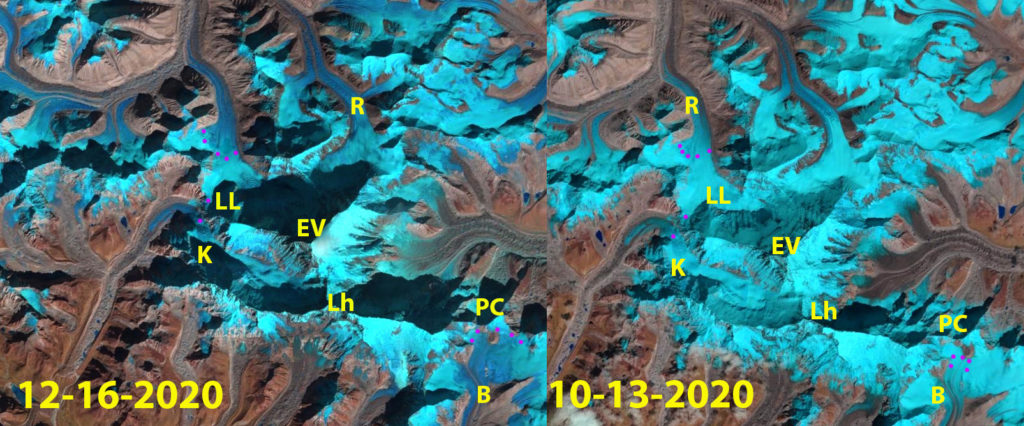

Rolwaling Glacier in October 13, 2020, December 16, 2020 and January 17, 2021 Landsat imagery indicating the snow line rise that has persisted into mid- winter. Snow line indicated by yellow dots.

Recent observations of rising snow lines on glaciers during the October- 2020-January 2021 period in Landsat imagery indicates that once again there is significant ablation occurring on Himalayan glaciers, as has been the case in several recent years (Pelto, 2017; 2019). For the first time we now have weather stations providing real time data in the Everest region that are high enough to transect the region of post monsoon snow line elevations, emplaced by the Rolex National Geographic Perpetual Planet expedition, with the Base Camp station at 5315 m and the South Col station at 6464 m (Matthews et al 2020). Combining the in-situ weather records and remote sensing data provides a unique opportunity to examine the impact of the warm and dry conditions during the 2020 post monsoon through 2020/2021 winter on Everest region glaciers. The ablation season is ongoing as of January 22, 2021, when will it end? How significant has ablation been during this interval? (For more information See NASA Earth Observatory and paper published by Pelto et al 2021)

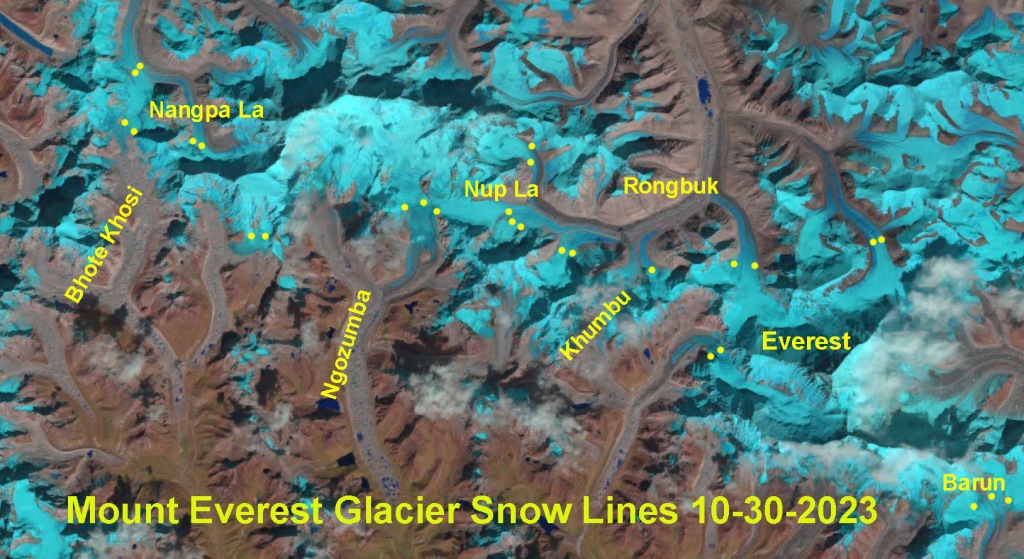

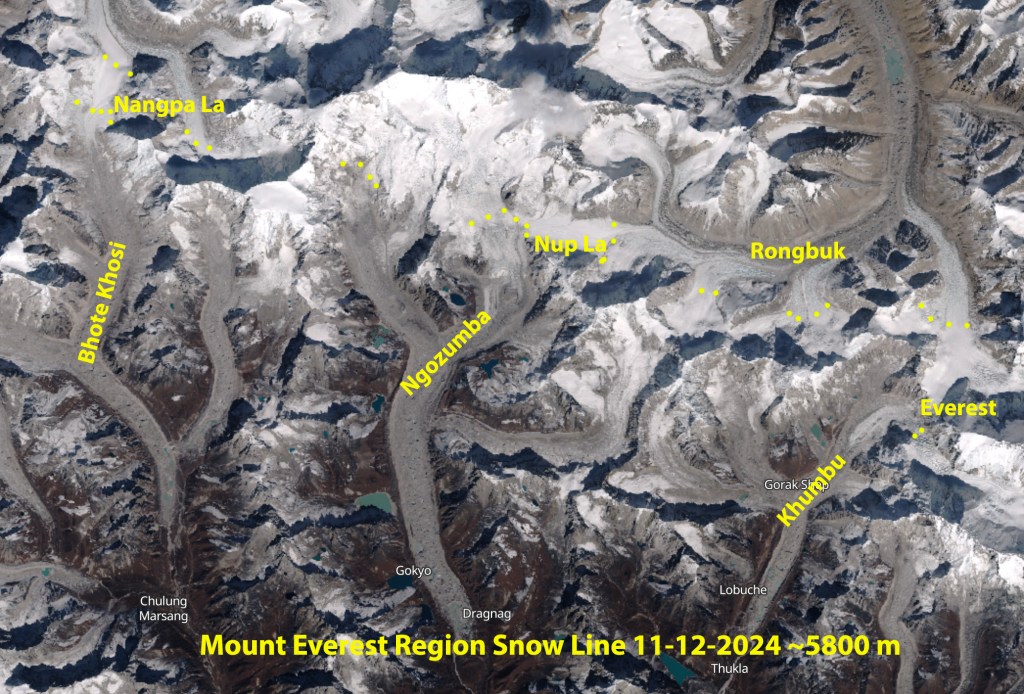

On October 13, 2020 Landsat imagery indicates the snow line on Mount Everest region glaciers averages 5600 m. By December 16 the mean snow line had risen to 5800 m (Pelto, 2020). On January 4-5, 2021 a minor snow event covered the area glaciers, which subsequently melted during an unusual warm period that extended from January 10-15. During this six-day January thaw daily maximum temperatures exceeded 3 C at the Base Camp weather station each day, peaking at 7 C on January 13 . At the Camp 2 weather station temperatures reached above -4 C each day during this period, with a maximum of 1 C on January 10 and 13. The daily maximum freezing line during the six-day period given the winter lapse rate of 0.54 C/100m is ~6000 m. Yes, mid-winter freezing levels at 6000 m on Mount Everest. This indicates melting even if limited in the vicinity of the snow line. From January 9-22 maximum temperatures have exceeded 0 C at Base Camp on 8 days.

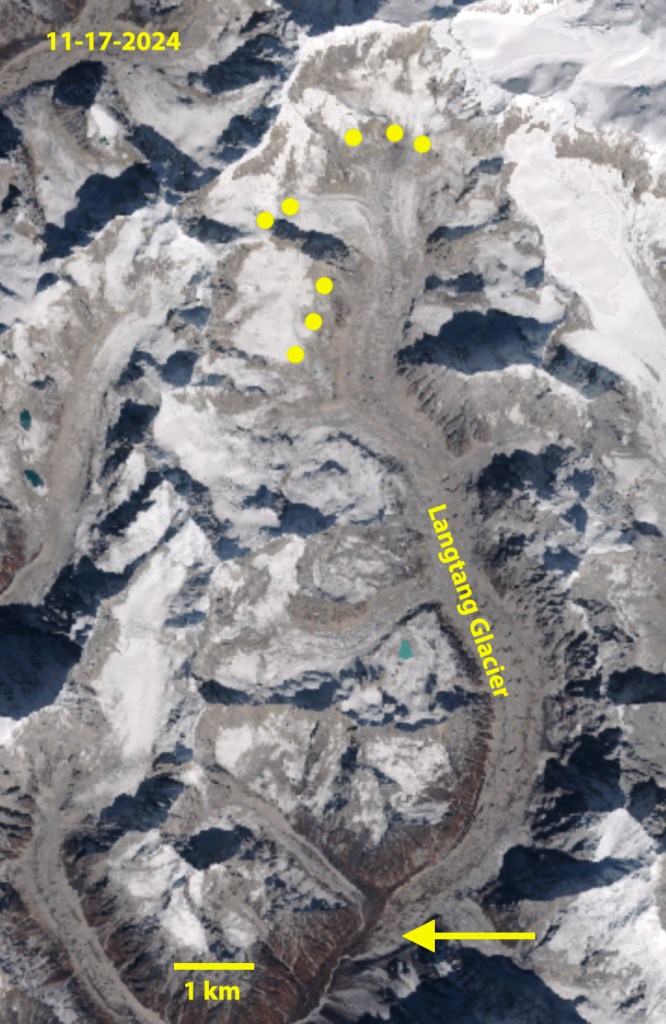

The impact is evident on Rolwaling Glacier which is 20 km south of Nanpa La and 35 km southwest of Mount Everest. This glacier is best known for being the primary glacier feeding the expanding and dangerous Tsho Rolpa, the lower part is often referred to as Trakarding Glacier (Rounce et al 2020). The glacier has a gentle slope allowing accurate assessment of the snow line. On October 13, 2020 the snow line is at 5725 m adjacent to Point A. By December 16 the snow line has risen to just south of Point B at 5800 m. On January 17 despite a small snow event on January 4-5, the snow line has risen above Point B to 5825 m. That the majority of the glacier remains snow free in mid winter and that ablation continues will hasten glacier retreat and Tsho Rolpa expansion.

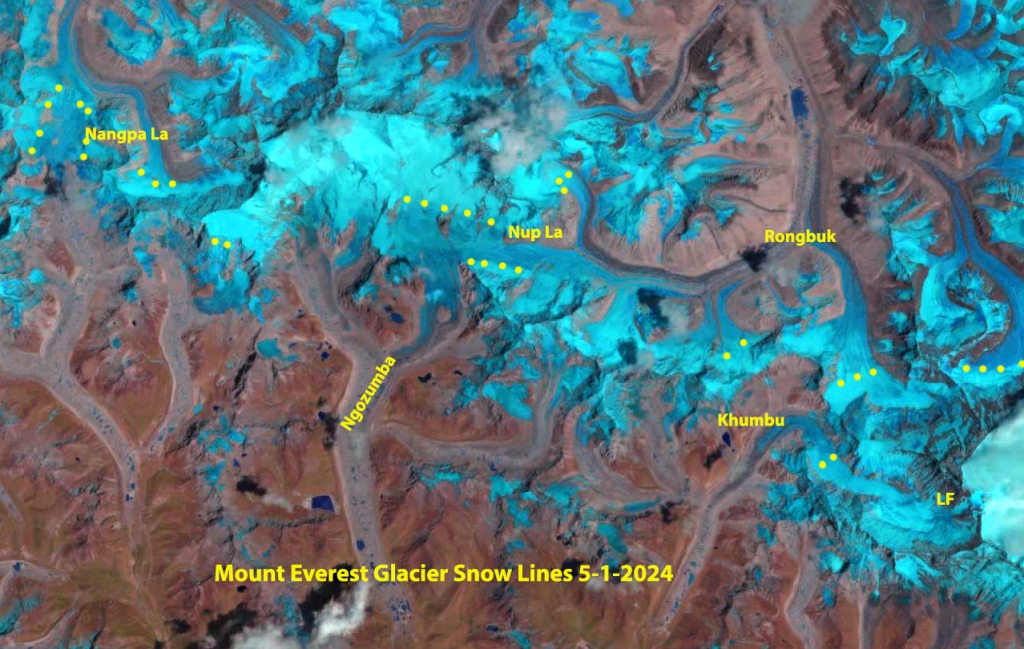

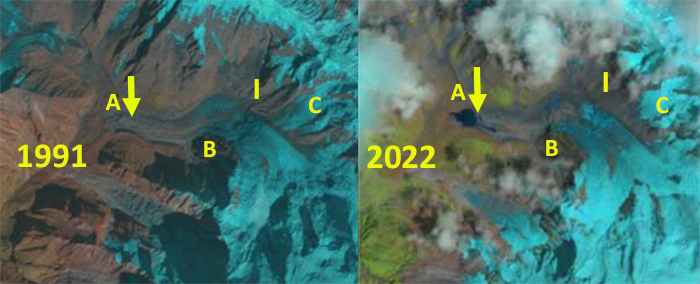

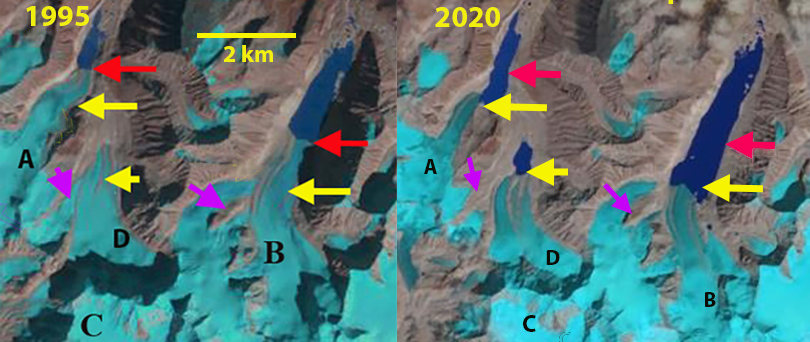

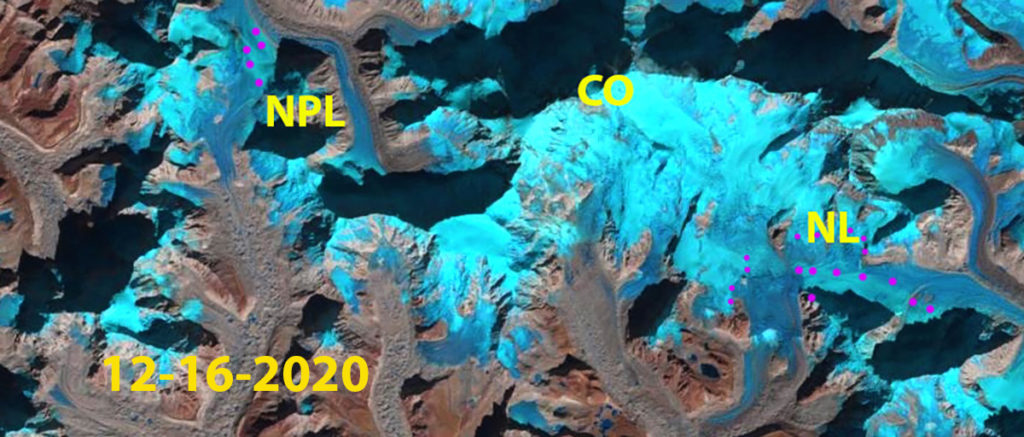

The snow line also remains above Nangpa La (5800 m) on January 17, 100 m higher than on October 13 when the snow line was at 5700 m, see below. Bolch et al (2011) indicated thinning on Khumbu Glacier was greatest in the clean ice zone, above the debris cover and below the snow line. This is both because of the higher albedo increasing the amount of solar radiation absorbed versus snowcover and the lack of an insulating debris cover. The rising snow line elevation has in the short term expanded this zone and bare ice is more susceptible to melt in the dry, sunny conditions of winter as temperatures are near 0 C.

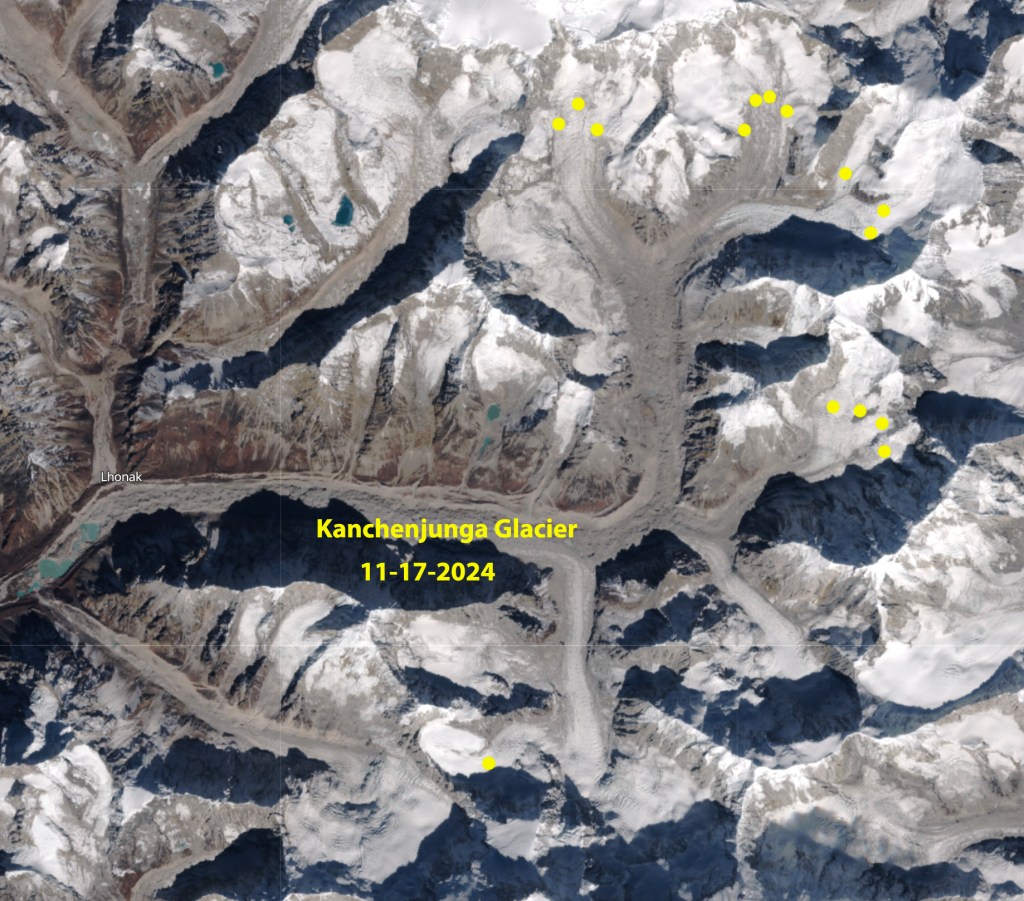

Mount Everest glaciers are summer accumulation type glaciers with ~75% of annual precipitation occurring during the summer monsoon, which is also the period of maximum melt lower on the glaciers (Wagnon et al 2013; Perry et al 2020). The freezing limit in summer separates the region where frozen precipitation or liquid precipitation predominates. Bocchiola et al (2020) report that on West Kangri Nup Glacier, tributary to Khumbu Glacier, in the 5400-5500 m range significant accumulation is no longer being retained through the summer monsoon, indicating the recent freezing limit. Perry et al (2020) identified a ~100 m rise in summer freezing level since 1980, to ~5400 m in the Mount Everest region, using ERA5 June, July, August, and September freezing-level heights. The rising freezing level is also evident in the ELA on Mera Glacier measured in October where Wagnon et al (2020) note that from 2008-2016 the ELA ranged from 5335-5680 m, and then rose to above 5700 m each year from 2017-2019.

October has been considered the end of the melt season in the region with little precipitation in the post monsoon and early winter season (October-December), averaging just ~3% of the total annual precipitation (Perry et al 2020). Winters (December-February) have been characterized as cold and dry, though they do have the most variable precipitation (Wagnon et al 2020). Salerno et al (2015) noted that winter ablation was only significant near the terminus of glaciers on the southern flank of Mount Everest. Litt et al (2019) use a glacier mass balance ablation model that does not account for potential winter ablation over much of the glacier. Sherpa et al (2017) examining the mass balance of Changri Nup concluded that winter mass balance is close to zero at all elevations based on the 2010-2015 period. The assumption that the ablation season ends in October, appears appropriate prior to the last decade. It is acknowledged that sublimation did occur in winter, but that was secondary to winter accumulation. Wagnon et al (2013) noted that ablation was significant in the ablation zone during the four winters surveyed from 2009-2012 at 5505 m on Mera Glacier in the Dudh Koshi Basin that Mount Everest south side drains into. This indicates that at least in recent years we need to account for winter ablation on Himalayan glaciers and the new high elevation weather record from Mount Everest are key to this Matthews et al (2020).

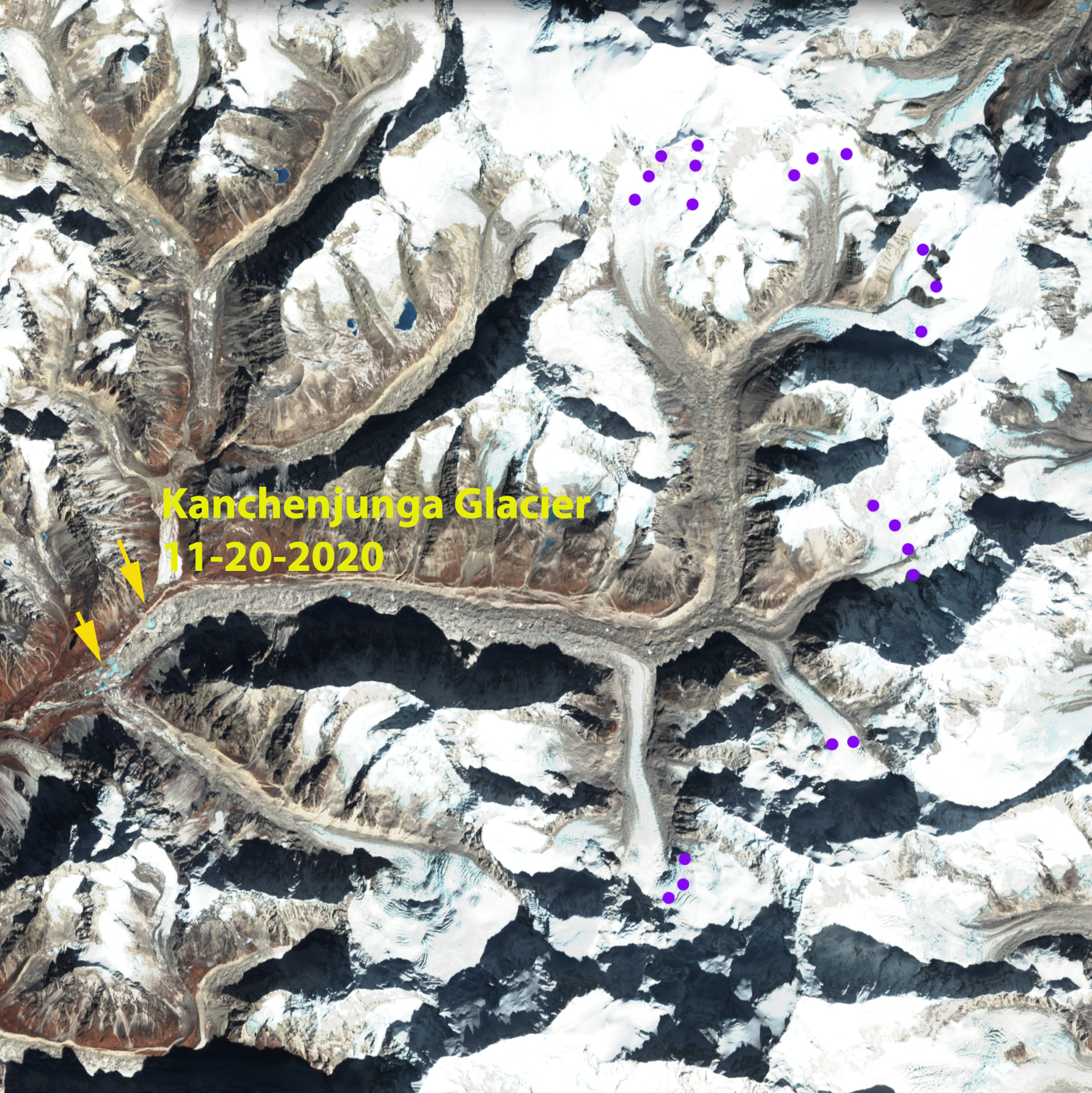

Nanpa La (NPL) and Nup La (NL) in October 13, 2020 and January 17, 2021 Landsat imagery indicating the snow line rise that has persisted into mid- winter. Snow line indicated by yellow dots.

Daily Photograph from the Rolex National Geographic Perpetual Planet expedition Base Camp weather station on January 22, indicating the lack of snowcover on the bare rock surfaces in foreground.