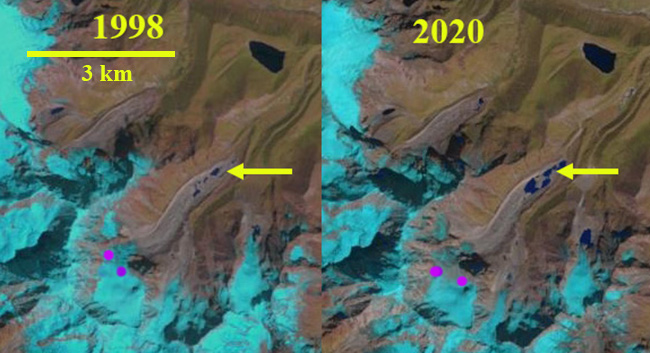

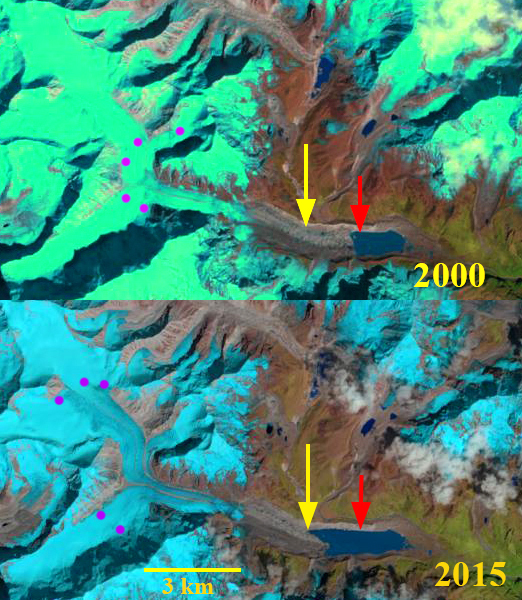

Baqupu Glacier in Landsat images from 1998 and 2020 indicating the expansion of supraglacial lakes in the terminus zone. Purples dots indicate the snowline in October of each year.

Baqupu Glacier is in the Poiqu River watershed in southern Tibet, China. The Poiqu River becomes the Bhote Koshi as it crosses into Nepal before joining the Sun Koshi River. The terminus of the glacier extending from 4500-4800 m is debris covered. An icefall extends from 4800-5300 m, above which the accumulation zone extends up to 5900 m. Shrestha et al (2010) examined the risk of a glacier lake outburst flood in the Sun Koshi basin from a Lumichimi Lake further north in the Poiqu Basin. They identified the potential for damage to the 45 MW Bhote Koshi Hydropower Plant. A July 2016 GLOF in the basin did in fact severely damage the Bhote Koshi Hydropower Plant. In a 2020 ICIMOD report (Bajracharya et al 2020) inventory of glacial lakes and potentially dangerous ones in the Koshi, Gandaki and Karnali Basin’s was updated. In the Sun Koshi Basin they mapped 181 lakes with an area of over 0.02 km2 with four being potentially dangerous lakes. The developing Baqupu Lake is not listed as potentially dangerous.

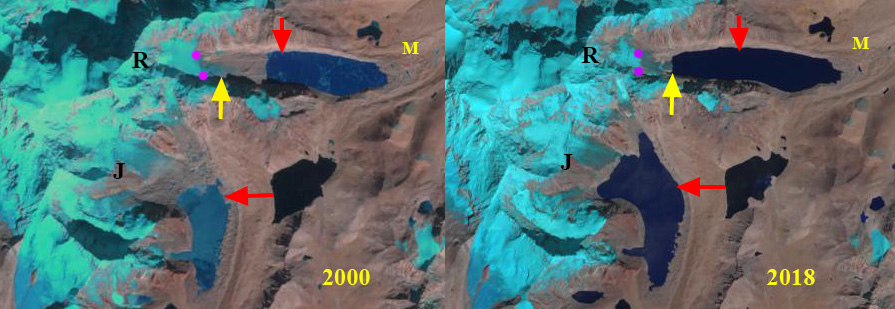

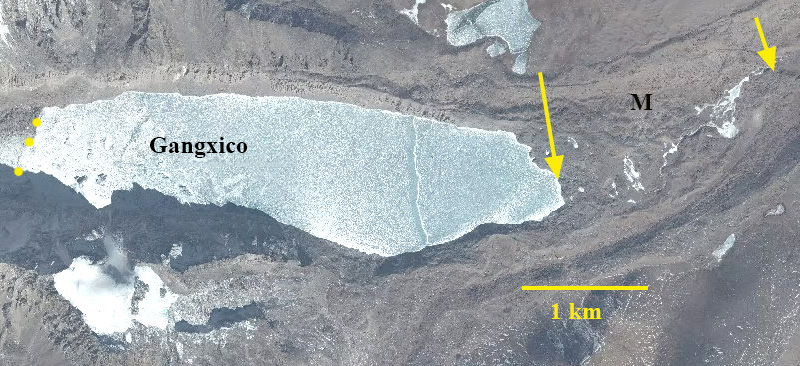

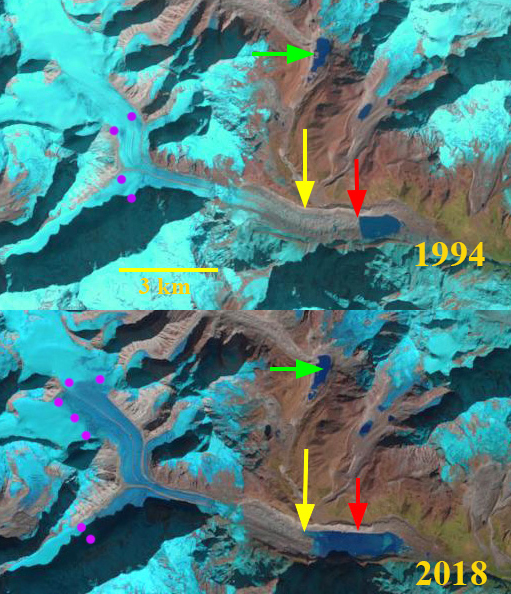

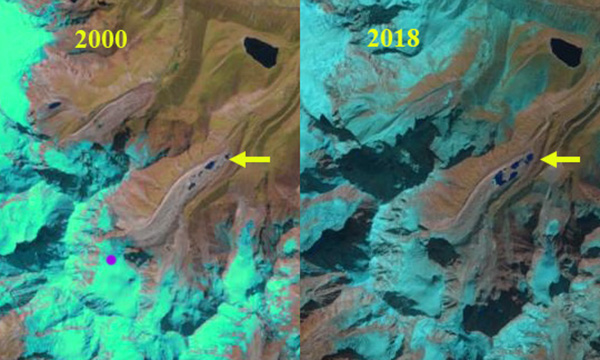

In 1998 Baqupu Glacier features a 0.03 km2 network of small supraglacial ponds at its surface at ~4500 m. The snowline is near the top of the icefall at 5200 m in October. By 2000 some evident expansion of the ponds is evident. The snowline in October is again near the top of the icefall at 5200 m. By 2018 there are four substantial ponds that have nearly coalesced. In 2019 the ponds have coalesced into two lakes. The snowline is just above the icefall at 5300 m. In 2020 the supraglacial lake system has an area of 0.24 km2. Average area of glacial lakes in basin is 0.12 km2 (Bajracharya et al 2020). The snowline is above the icefall at ~5400 m. The persistent equilibrium line above the icefall during this period is reducing the flux through the icefall to the debris covered tongue. The tongue is increasingly stagnant and the thinning will lead to continued lake expansion into what will be a proglacial lake. This expansion is similar to that on Rongbuk Glacier, while other nearby lakes have had expanding proglacial lakes, Drogpa Nagtsang Glacier and Yanong Glacier.

. Ya

Ya

Baqupu Glacier in Landsat images from 2000 and 2018 indicating the expansion of supraglacial lakes in the terminus zone. Purples dots indicate the snowline in October of each year.

Baqupu Glacier in Digital Globe image from 2019. A=Accumulation zone; D=Debris cover, I=Icefall, S=Supraglacial lake.