[ngg_images source=”galleries” container_ids=”22″ display_type=”photocrati-nextgen_basic_imagebrowser” ajax_pagination=”1″ template=”/nas/wp/www/sites/blogsorg/wp-content/plugins/nextgen-gallery/products/photocrati_nextgen/modules/ngglegacy/view/imagebrowser-caption.php” order_by=”sortorder” order_direction=”ASC” returns=”included” maximum_entity_count=”500″]

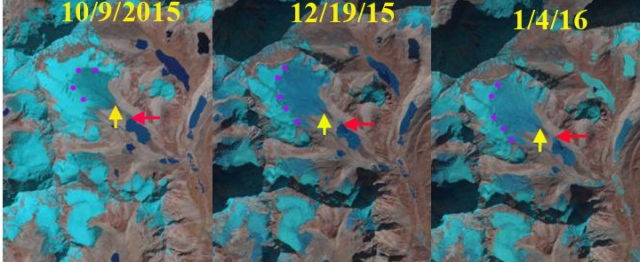

Purple dots indicate the transient snowline on Gangotri Glacier in the fall and early winter of 2016. Red arrow indicates the terminus of the glacier.

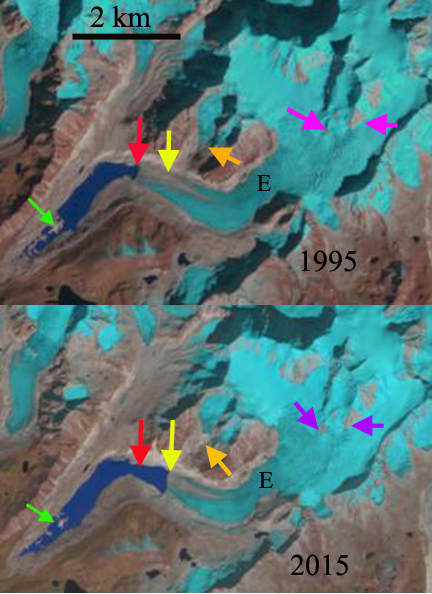

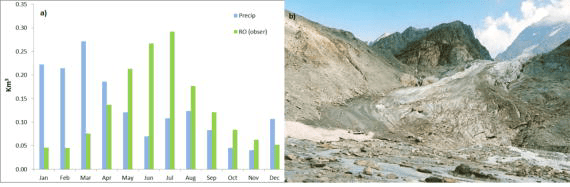

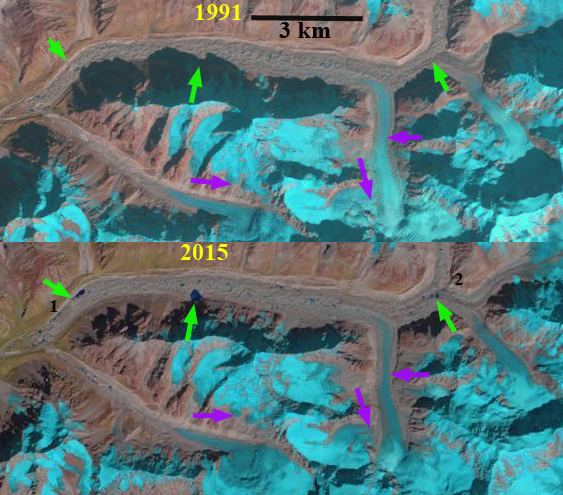

The Gangotri Glacier is the largest glacier in the Bhagirathi River watershed, situated in the Uttarkashi District, India. It is one of the larger glaciers in the Himalaya, and like all of the nearby Himalayan glaciers is retreating significantly. Gangotri Glacier provides hydropower as its meltwater passes through three hydropower plants generating 1430 MW, including the 1000 MW Tehri Dam and reservoir and Maneri Bhali I and II, see map below. From 1968-2006 the glacier retreated 800 meters, close to 20 meters per year (Bhambri et al, 2012). The glacier continues to thin and tributary inflow decline, while terminus retreat is slowe due to the thick debris cover that heavily insulates the ice. Bhambri et al (2011) inventoried glaciers in the upper Bhagirathi basin and found they lost 9 square kilometers in area, 3.3% to the total, from 1968 to 2006. They further noted that recession rates have increased since 1990 and that the number of glaciers increased from 82 in 1968 to 88 in 2006 due to fragmentation of glaciers. From 1968 to 2006, the debris-covered glacier area increased by ~12% in the upper Bhagirathi basin. Bhattachaya et al (2016) expanded on this work noting that the velocity of Gangotri Glacier declined during 2006-2014 by 6.7% from 1993-2006, this suggests reduced accumulation being funneled downglacier. They also noted an increase in the rate of debris-covered area expansion on the main trunk of Gangotri Glacier from 2006-2015, which is indicative of an expanding ablation zone. Bhattachaya et al (2016) report a retreat rate of 9 m/year 2006-2015, which is less than before, but the down-wasting in the same period 2006-2015 was higher than during 1968-2006. The study reinforced that glacier retreat is a delayed response to climate change, whereas glacier mass balance is a more direct and immediate response. This underlines the importance of mass balance studies for assessing climate change impact on glaciers,that the World Glacier Monitoring Service has emphasized. Gangotri Glacier is a summer accumulation glacier with the peak ablation period low on the glacier coinciding with peak snowfall high on the glacier during the summer monsoon. In the post monsoon period of October and November precipitation is low and melt rates decline, Haritashya et al (2006) note a sharp decline in discharge and suspended sediment load beginning in October. . Kundu et al (2015) from Sept. 2012 to January 2013 noted that the snowline elevation varied little, with the highest elevation being 5174 m and the lowest 5080 m.

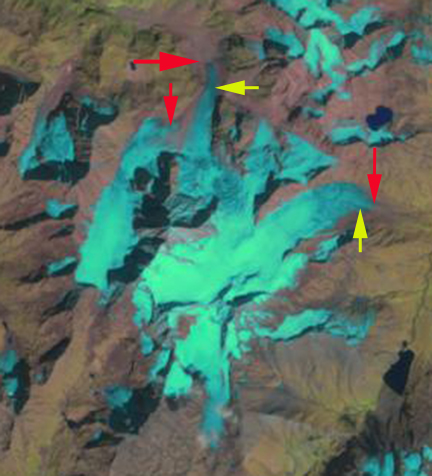

The increase in temperature has led to a tendency for snowlines to rise in the post monsoon period and remain high into the winter season on many Himalayan glaciers. In 2016 this has been the case. On October 9, 2016 a Sentinel image indicates the snowline is at 4850 m on the main trunk and on the tributary Ghanohim Glacier the snowline, while it is 4750 m on the tributaryKirti Glacier. A Landsat image from October 13th indicates the snowline on Kirti has risen to 4800 m, and remains at 4850 on the main trunk and Ghanohim Glacier. By November 30th a Landsat image indicates the snowline has risen to 5400 m on the main trunk and Ghanohim, the snowline is at 5800-5900 m on the glaciers in the Swachhand tributary valley, at 5600 m on Maiandi Glacier and 5700 m on the last tributary entering from the north. Note the impact of radiational shading is apparent on the main trunk with the snowline descending down the middle of the main trunk from 5400 m to 5100 m and on Kirti Glacier which is too dark to confidently discern the snowline. Temperatures are typically cool in December, but sunshine is common. A Sentinel image from December 8th and Landsat from Dec. 9th indicate that the snowline remains approximately the same as on Nov. 30th. The accumulation area ratio is the percentage of a glacier in the accumulation zone and is typically above 50%. On Gangotri Glacier in December 2016 the accumulation area ratio is only 20%, indicating a large mass balance deficit. High winter snowlines on Chutenjima Glacier, Tibet, from October, 2015 to February 2016. This tendency is also noted at Nup La-West Rongbuk Glacier, on the Nepal-China border, West Hongu Glacier, Nepal and Lhonak Glacier, Sikkim.

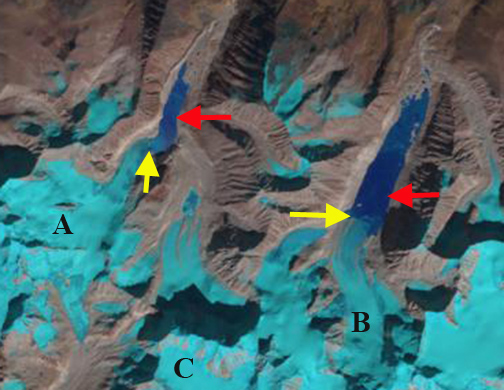

Gangotri Glacier and its key tributaries, with the red line being the outline of the glacier from GLIMS.

Hydropower in the Bhagirathi River watershed