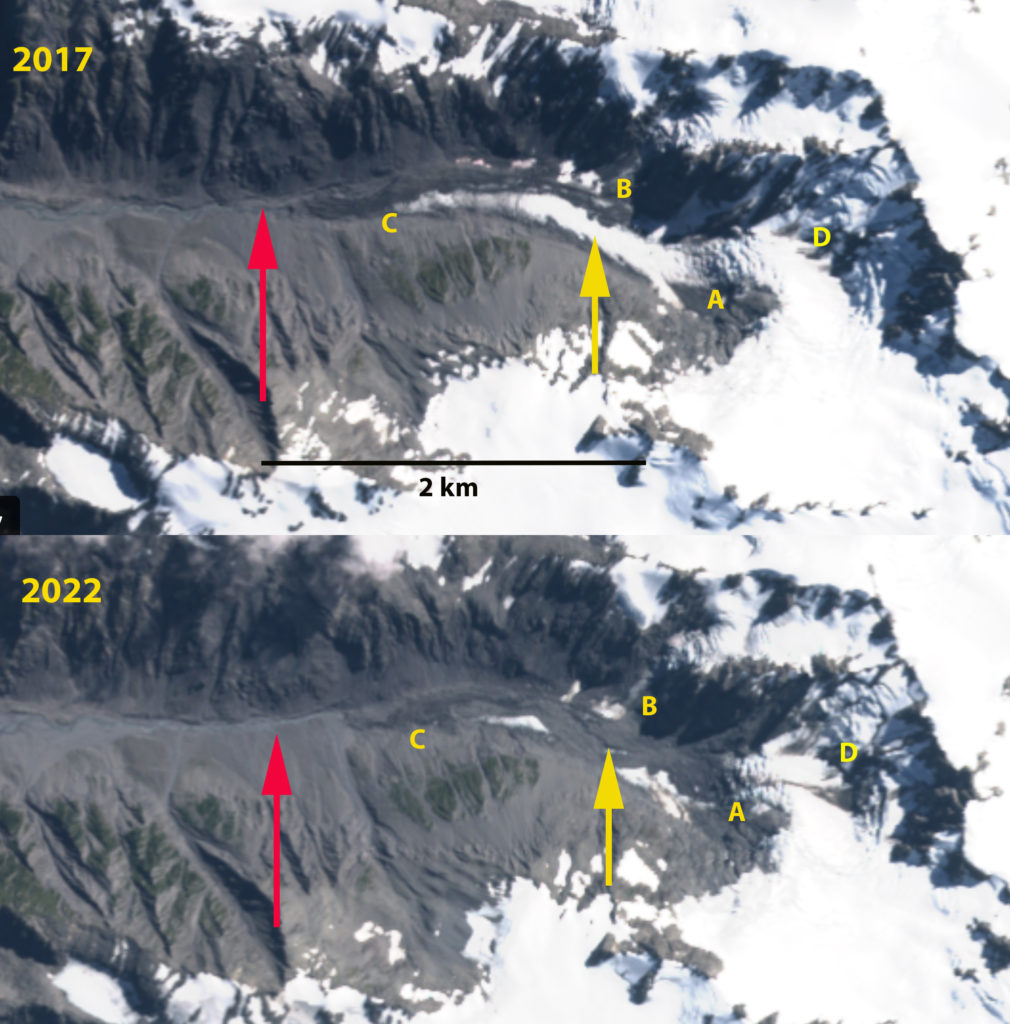

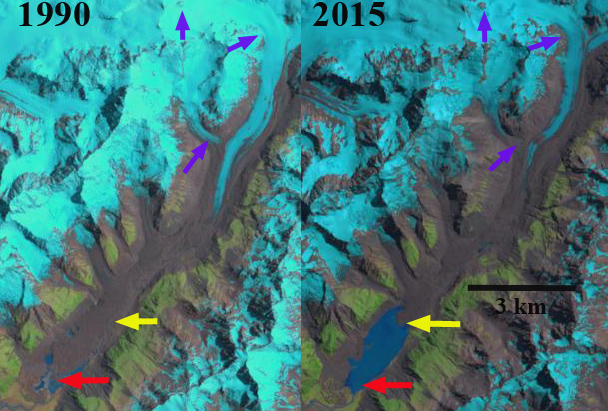

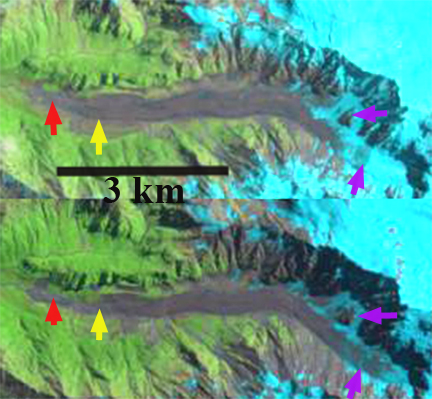

Victoria Glacier in Sentinel images from February 2017 and February 2022. Red arrow is 2002 terminus location, yellow arrow marks 2022 debris cover take over and beginning of stagnating ice region. Point C is lowest point of clean ice in 2017 and just above terminus in 2022. Point A, B and D are icefalls where detachment is underway.

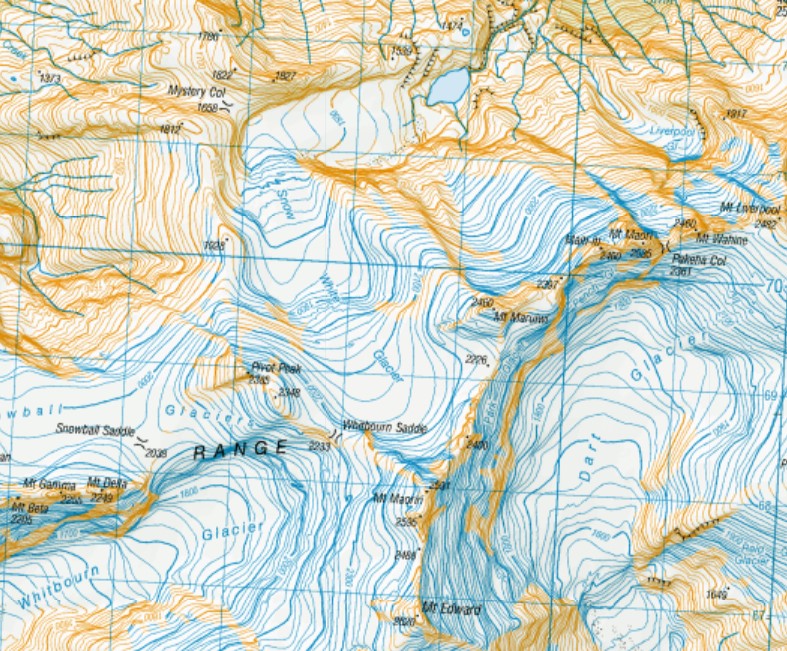

Victoria Glacier in New Zealand’s Southern Alps is the westward draining valley glacier between Fox and Franz Josef Glacier. Victoria Glacier has limited terminus observations over the last 25 years indicating a stationary terminus position from 1998-20o1, retreat in 2005, advance in 2008 and 2009, stationary position 2010-2013 and retreat from 2014-2017 (WGMS, 2021). Here Landsat and Sentinel imagery are used to explore changes to this glacier from 2002-2022. Chinn and Chinn (2020) reported a 3.7 m/year rise in the mean New Zealand end of summer snowline on glaciers over the last 40 years, which is driving mass loss and retreat of glaciers across the range. Baumann et al (2020) provide an inventory of NZ glaciers noting that most of the glacier tongues below 1000 m are debris covered including several that are detached and a 21% decrease in area was noted for the 1978-2016.

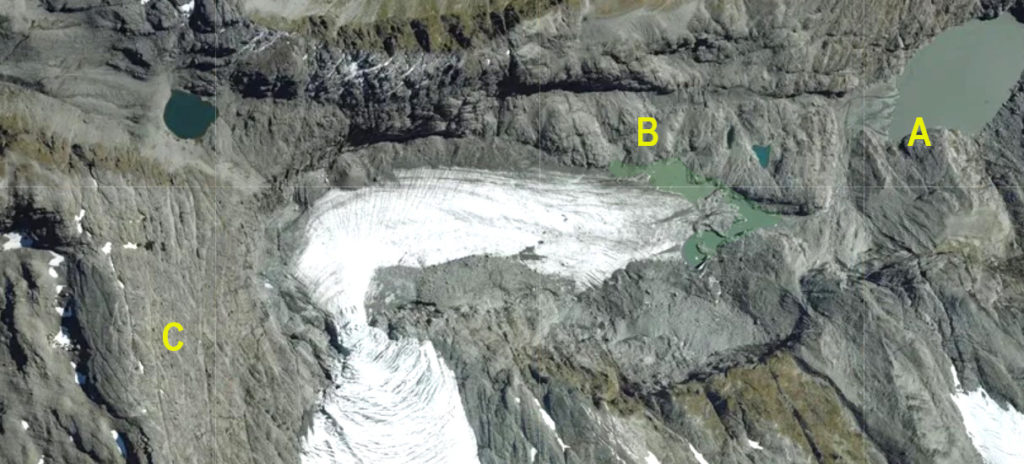

In 2002 the glacier extends 2.3 km downvalley from the base of the Icefall at Point A. The active ice front marking the terminus is at 1150 m and clean ice begins 300 m upglacier from the terminus. In 2017 following first a period of advance and retreat the terminus has retreated ~100 m since 2002, clean ice begins 400 m from the terminus, at Point C .The width of the clean ice area is reduced from 2002. In 2017 there is active crevassing in the icefalls at Point and D extending to the valley trunk below. At Point B there is a clean ice connection in 2017, but not active crevassing to the base of the icefall. From 2017-2022 rapid downwasting of the terminus tongue resulted in a 500 m retreat of the active ice front, which is near Point C. There is only small patch of clean ice in the last 1 km of the glacier. Crevassing in the icefalls at Point B and D no longer extends all the way to the valley trunk of the glacier. At the yellow arrow is both where debris cover dominates in 2022, but also marks the beginning of a deeply carved surface stream, indicating near stagnation of the glacier in this region. The recent high snowlines observed in the annual end of summer surveys (NIWA, 2018) will lead to continued reduced flux of ice through the icefalls and detachment at Point B and D in the near future.

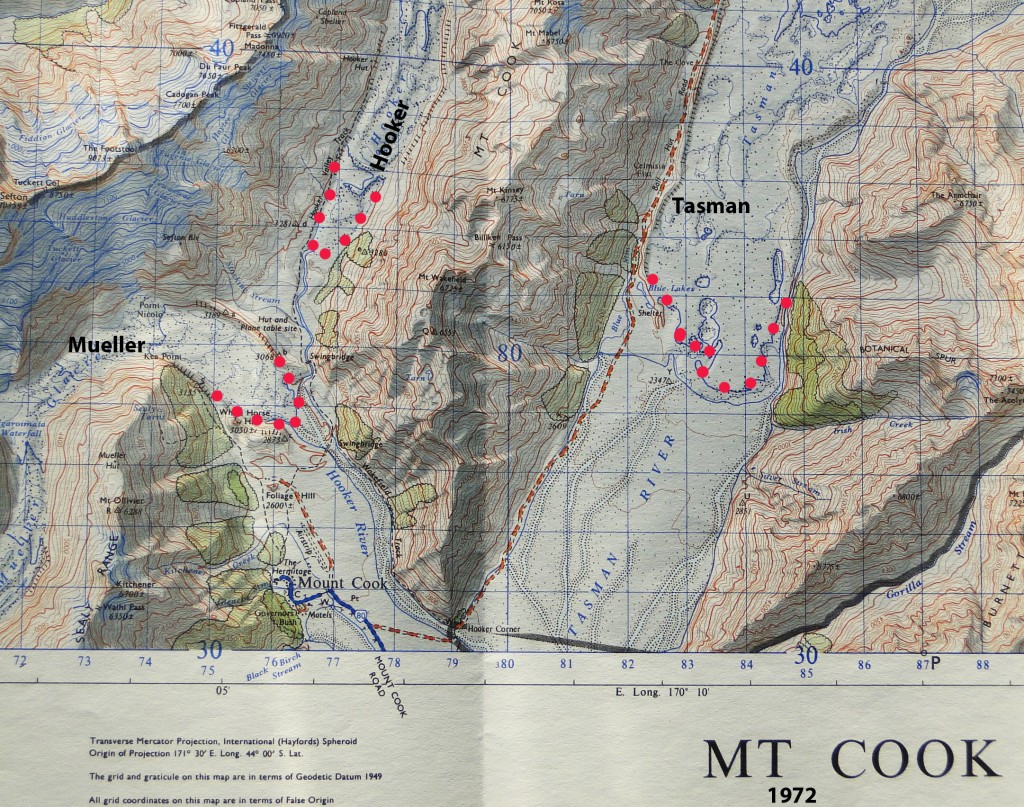

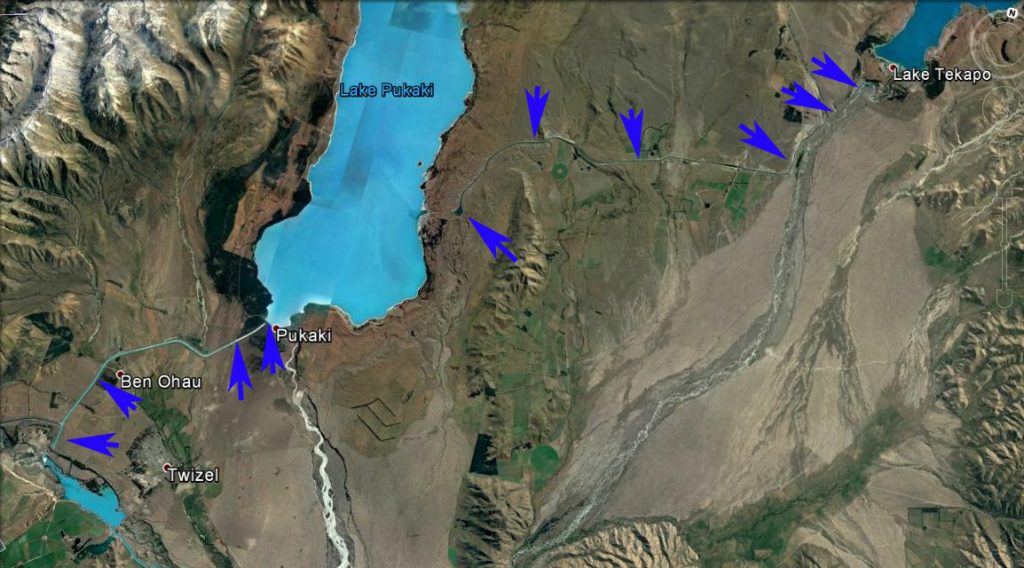

Victoria Glacier topographic map with flow arrows and specific elevations.

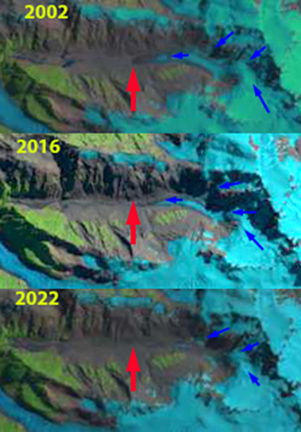

Victoria Glacier in 2002, 2016 and 2022 Landsat images.Red arrow marks 2002 terminus position, blue arrows indicate flow lines.