Easton Glacier in 1990, 2003 and 2015 from same location. Below Painting by Jill Pelto of crevasse assessment using a camline.

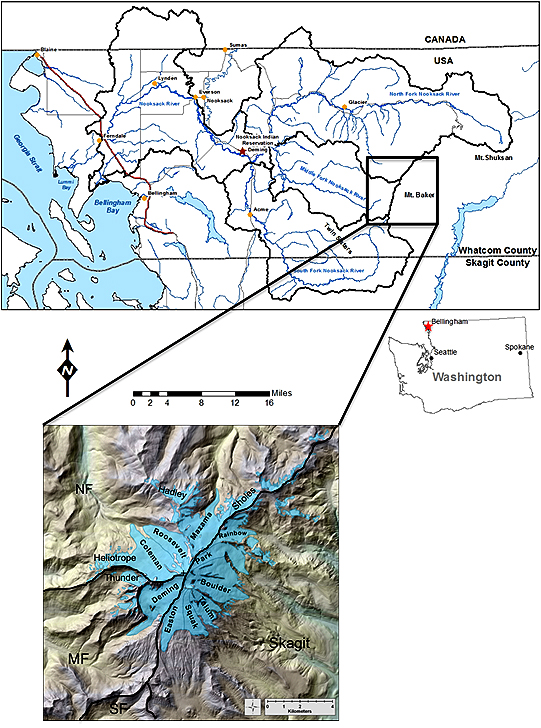

This is the story of how you develop and conduct a long term glacier monitoring program. We have been monitoring the annual mass balance of Easton Glacier on Mount Baker, a stratovolcano in the North Cascade Range, Washington since 1990. This is one of nine glaciers we are continuing to monitor, seven of which have a 32 year long record. The initial exploration done in the pre-internet days required visiting libraries to look at topographic maps and buying a guide book to trails for the area. This was followed by actual letters, not much email then, to climbers who had explored the glacier in the past, for old photographs. Armed with photographs and maps we then determined where to locate base camp and how to access the glacier. The first year is always a test to make sure logistically you can reach enough of the glacier to actually complete the mass balance work with a sufficiently representative network of measurement sites. The second test is if you can stand the access hike, campsite, and glacier navigation, to do this every year for decades; if the answer is no, move on. That was the case on Boulder Glacier, also on Mount Baker: poor trail conditions and savage bugs, were the primary issue. Next we return to the glacier at the same time each year, completing the same measurements each year averaging 210 measurements of snow depth or snow melt annually. This occurs whether it is gorgeous and sunny, hot, cold, snowy, rainy, or recently on this glacier dealing with thunderstorms. You wake up, have your oatmeal and coffee/cider/tea, and get to work. Lunch on the snow features bagels, dried fruit, and trail mix. Happy hour features tang or hot chocolate depending on the weather. It is then couscous, rice, pasta or quinoa for dinner, with some added dried vegetable or avocado. The sun goes behind a mountain ridge and temperatures fall, and the tent is the haven until the sun returns. Repeat this 130 times on this glacier and you have a 25 year record. During this period the glacier has lost 16.1 m of water equivalent thickness, almost 18 m of thickness. For a glacier that averaged 70 m in thickness this is nearly 25% of the volume of the glacier gone. The glacier has not maintained sufficient snow cover at the end of the summer to have a positive balance, this is the accumulation area ratio, note below. The glacier has retreated 315 m from 1990-2015. This data is reported annually to the World Glacier Monitoring Service. The glacier has also slowed its movement as it has thinned, evidenced by a reduction in number of crevasses. During this time we have collaborated with researchers examining the ice worms, soil microbes/chemistry, and weather conditions on the ice. This glacier supplies runoff to Baker Lake and its associated hydropower projects. Our annual measurements here and on Rainbow Glacier and Lower Curtis Glacier in the same watershed provide a direct assessment of the contribution of glaciers to Baker Lake. The glacier is adjacent to Deming Glacier, which supplies water to Bellingham, WA. The Deming is too difficult to access, and we use the Easton Glacier to understand timing and magnitude of glacier runoff from Deming Glacier.

The glacier terminates at an elevation of 1650 m, but thinning and marginal retreat extends much higher. A few areas of bedrock have begun to emerge from beneath the ice as high as 2200 m. The changes in ice thickness are minor above 2500 m, indicating this glacier can retreat to a new equilibrium point with current climate.

Mass balance, terminus and supra glacial stream assessment are illustrated in the video, Filmed by Mauri Pelto, Jill Pelto, Melanie Gajewski, with music from Scott Powers.

Mass balance Map in 2010 of Easton Glacier used in the field for reference in following years.

Accumulation Area Ratio/Mass balance relationship for Easton Glacier

Despite the advantages of snow accumulation the glaciers mass balance since 1984 has average -0.5 m a year for a cumulative loss of 13 m. For a glacier that averages 60 m in thickness this is over 20% of its volume. Details of the

Despite the advantages of snow accumulation the glaciers mass balance since 1984 has average -0.5 m a year for a cumulative loss of 13 m. For a glacier that averages 60 m in thickness this is over 20% of its volume. Details of the