Lemon Creek Glacier (L) with the snowline (black line) indicated in Landsat images from July 5, July 30 and Sept. 16 2018. P=Ptarmigan Glacier, T=Thomas Glacier, red arrow is the 1948 terminus location. A,B and C mark firn horizons exposed by the loss of all snowpack in the accumulation zone.

The summer of 2018 was exceptional for warmth in Southeast Alaska. July was the most unusual with Juneau recording daily highs above 70 F on 18 days, including 12 consecutive days at the end of the month. The average temperature in July in Juneau was 2.4 C above average and the warmest average monthly temperature in history. Precipitation was recorded on just 6 days of precipitation at the Long Lake SNOTEL site in the mountains near Juneau. This resulted in the highest observed snowline of the 70 year record on Taku Glacier, a 25 km2 snow swamp developing in three days on Lowell Glacier and the loss of all snowpack on Lemon Creek Glacier. For a glacier to be in equilibrium most glaciers need to be more than 50% snowcovered. On Lemon Creek Glacier at the end of the summer the glacier must be covered 62% to be in equilibrium (Pelto et al 2013). The Lemon Creek Glacier is a reference glacier of the World Glacier Monitoring Service, with mass balance measured since 1953 by the Juneau Icefield Research Program (JIRP). The USGS began monitoring the glacier in 2016 and currently reports mass balance to WGMS, Chris McNeil (USGS) is leading a reanalysis of the mass balance record. The cumulative mass loss from 1953-2018 is ~37 m w.e, with 2018 having the most negative balance of -2.31 m w.e. The area of the glacier has declined from 12.8 square kilometers in 1948 to 9.7 square kilometers in 2018, a 24% decline. For the glacier to provide an equivalent runoff ablation rates would have had to rise by 24%.

In 2018 on July 5 2018 the snowline on Lemon Creek Glacier was at 950 m. From July 4-6 a series of snowpits were dug on the glacier by JIRP yielding a retained snowpack ranging from 0.9 m (water equivalent=w.e.) to 1.2 m (w.e.). One of the snowpits with 0.9 m w.e. was at 1075 m. On July 30 the snowline had reached 1100 m, indicating approximately 0.9 m of snow ablation in that 21 day interval. Because ice ablates faster than snow, 36% faster on Lemon Creek Glacier this would equate to ~1.2 m of ice ablation. By September 2 the snowline had risen above the top of the glacier, with one small snowpatch in the northwest corner at 1200 m, firn horizon exposed by snowpack loss are evident . This remains the case in the Sept. 16 image. The small snowpatch also melted away by the end of September. There was no accumulation zone for the third time in the last five years,indicating this glacier cannot survive current climate (Pelto, 2010).

The consistency of the balance gradient, seen below from year to year allows for determination of melt rates and runoff based on the rise of the snowline. The transient snow line migration rate times the balance gradient yields ablation rate at the snowline (Pelto, 2011). The impact of a greater area of surface ice exposed is increased ablation. To illustrate this impact if we as an example take a day with a mean temperature of 10 C:

This would yield 350,000 m3 of melt on July 5, the glacier was 23% bare ice and 77% snow cover on this date.

This would yield 382,000 m3 of melt on July 30, the glacier was 41% bare ice and 59% snow cover on this date.

This would yield 480,000 m3 of melt on Sept. 16, the glacier was 97% bare ice/old firn and 3% snow cover on this date.

The actual July 5 temperature for Lemon Creek Glacier was 12 C. This yields 420,000 m3 of runoff.

The actual July 30 temperature for Lemon Creek Glacier was 11.5 C. This yields 440,000 m3 of runoff.

The actual Sept. 16 temperature for Lemon Creek Glacier was 1.5 C. This yields 72,000 m3 of runoff.

Base map of Lemon Creek Glacier from 2014 prepared by Chris McNeil (JIRP and USGS). The blue dots are JIRP 2018 snowpit locations and the lines are the snowline on the respective dates. Camp 17 is the JIRP camp used for Lemon Creek Glacier research, including the upcoming 2019 field season.

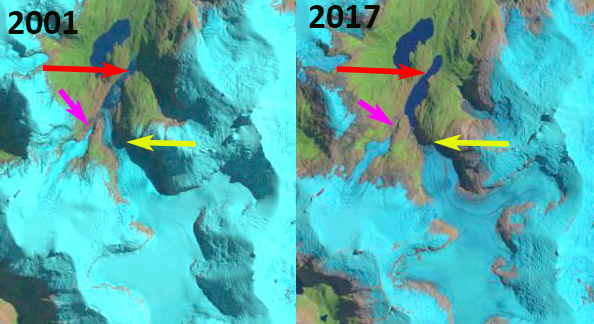

USGS topographic map based on 1948 aerial photographs. On right is the hillshade image from 2011, margin is the black dots.

Image of the glacier on 9/2/2018 indicating firn horizons and the small remaining snowpack in the southwest corner.

Balance gradient of Lemon Creek Glacier, note the consistency.