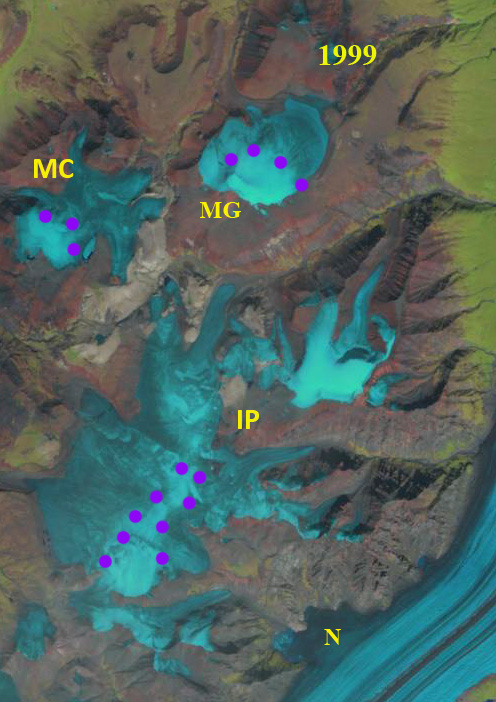

Mount Gordon Icefield (MG) Mesa Creek Icefield (MC) and Icefield Plateau (IP) in 2016 and 2017 Landsat imagery. The purple dots indicate the areas with retained snowcover in both years. Nabesna Glacier (N) is the largest glacier in the Wrangell Mountains, just a corner seen here.

Mount Gordon Icefield (MG) Mesa Creek Icefield (MC) and Icefield Plateau (IP) are three neighboring Icefields in the Wrangell-Saint Elias National Park and Preserve in Alaska. Each has a principal accumulation area between 2300 and 2550 m, with a limited area above . The area of Mount Gordon Icefield is ~10 square kilometers, Mesa Creek Icefield ~12 square kilometers and Icefield Plateau ~35 square kilometers. This is a region that has been experiencing significant mass loss. Das et al (2014) used repeat altimetry measurements to identify accelerated mass loss over the Wrangell Mountains, from –0.07 ± 0.19 m w.e./year during 1957–2000 to –0.24 m w.e./year during 2000–07. Larsen et al (2015) identified that the Wrangell Mountains experienced a mass balance of -0.5 to -1 m/year from 1994–2013 using laser altimetry.

On August 17, 2016 less than 10% of the Icefield Plateau is snowcovered, with the snowline at 2500 m. The snowline is at 2400 m on Mount Gordon Icefield and Mesa Creek Icefield with 30% of each icefield retaining snowcover. On August 4, 2017 there is insignificant retained snowcover on Mesa Creek Icefield. The snowline is at 2500 m on both Mount Gordon Icefield and Icefield Plateau with less than 10% overall retained snowcover. The lack of retained snowcover across most of the former accumulation area from 2300-2550 m indicates these icefields will have substantial icefield wide thinning. In addition the lack of a persistent substantial accumulation zone indicates the icefield will not survive, though a small mountain glacier may remain on the est side of Mount Gordon and the southern edge of the Icefield Plateau. In 2018 there is not a good cloud free August image from this region. The high snowline and rapid melt on nearby Lowell Glacier suggest the snowline would again have been high. This will lead to substantial retreat of the icefield margins and is indicative of the retreat of large glaciers in the range such as Nizina Glacier or Yakutat Glacier in the Saint Elias Range.

Mount Gordon Icefield (MG) Mesa Creek Icefield (MC) and Icefield Plateau (IP) in topographic map.

Mount Gordon Icefield (MG) Mesa Creek Icefield (MC) and Icefield Plateau (IP) in 1999 Landsat image. The purple dots indicate areas with retained snowcover. N=Nabesna Glacier.

Mount Gordon Icefield (MG) Mesa Creek Icefield (MC) and Icefield Plateau (IP) in 2001 Landsat image. The icefield are nearly fully covered with snow. N=Nabesna Glacier.