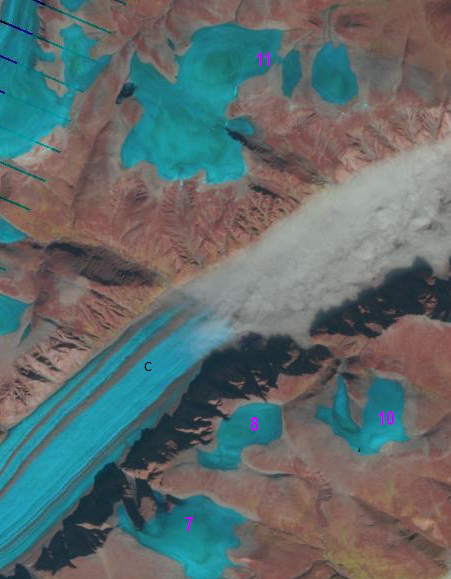

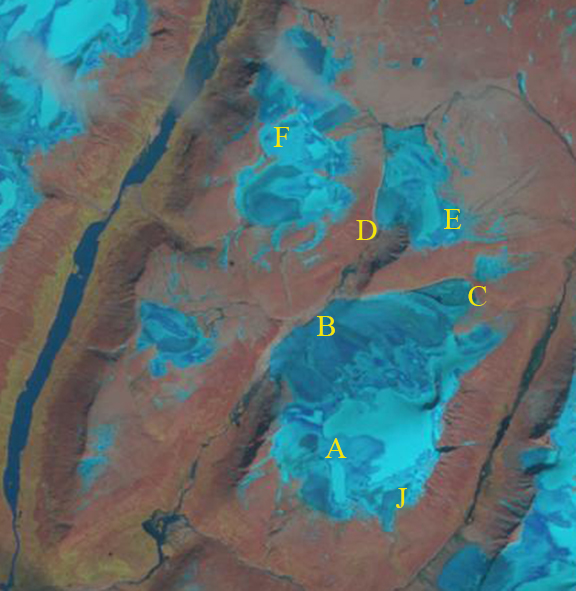

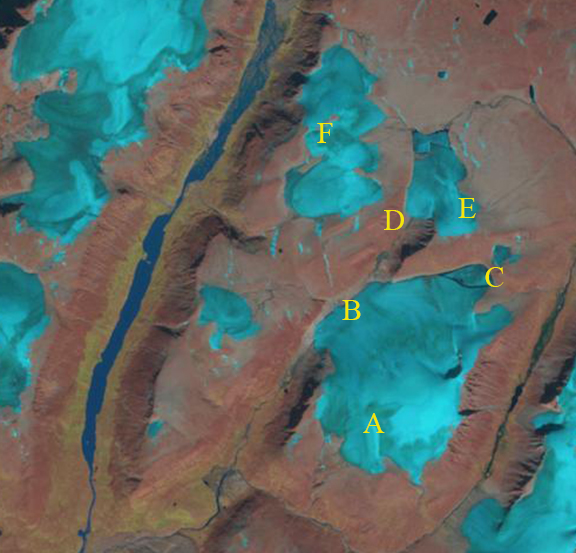

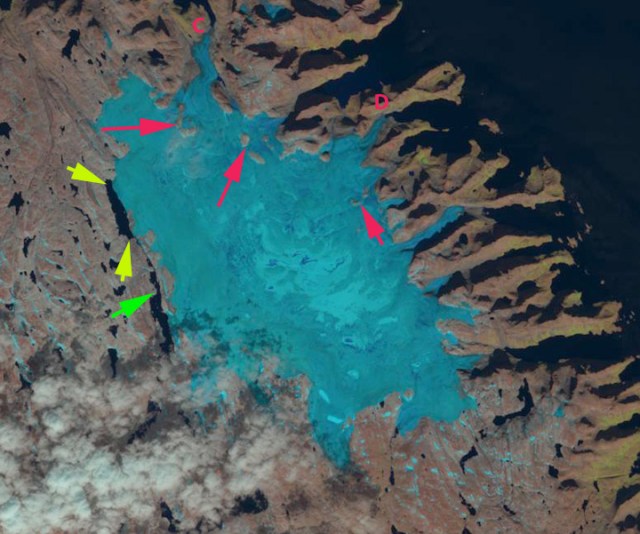

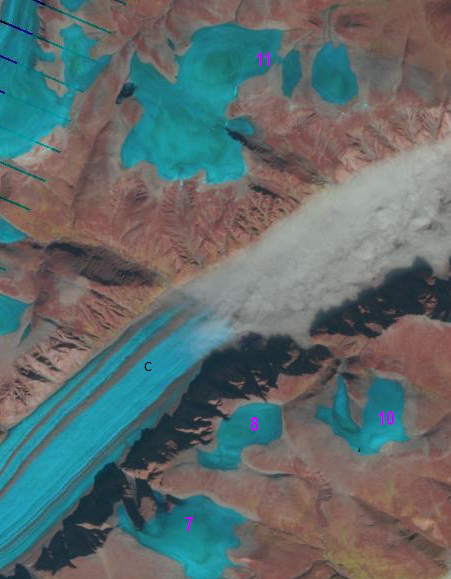

A Landsat image from 1989 and a Sentinel 2 image from2016 illustrate the retreat of Coronation Glacier. Red arrows indicate the 1989 terminus and yellow arrows the 2016 terminus location. Purple numbers 1-5 indicate locations of tributary retreat or thinning. Purple numbers 6-9 are icecaps that did not retain snowcover in 2016.

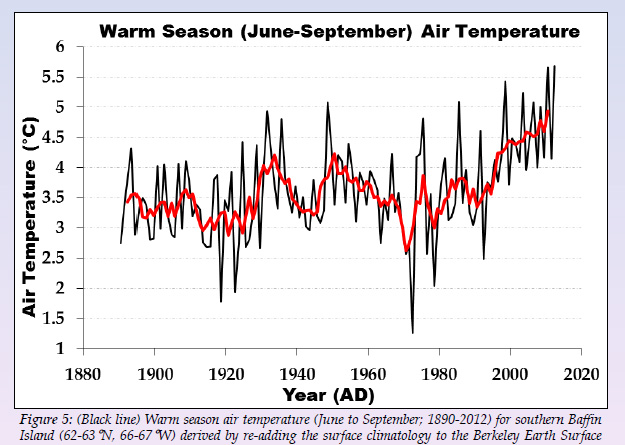

Coronation Glacier is the largest outlet glacier of the Penny Ice Cap on Baffin Island. The glacier has an area of ~660 square kilometers and extends 35 km from the edge of the ice cap terminating in Coronation Fjord. On January 10, 2017 an Art Exhibit “Into the Arctic” by Cory Trepanier opens at the Canadian Embassy in Washington DC, the first stop in a two year North American tour. The exhibit features some amazing paintings of Coronation Glacier (see below). Here we examine the response driven by climate change of this glacier from 1989 to 2016 using Landsat and Sentinel Imagery. Van Wychen et al (2015) observe that it is the largest glacier from any of the Baffin Island Ice Caps with discharge greater than 10 Mt/year. They observed peak velocities of 100-120 m/year in the descent from the main ice cap into the main glacier valley. The velocity in the terminus section is ~30 meters/year. Syvitski (1992) noted that Coronation glacier retreated at an average rate of 12 meters per year from 1890-1988. Zdanowizc et al (2012) noted that in recent years the ice cap has experienced heightened melt, a longer melt season and that little retained snowpack survives the summer, that most of the retained accumulation is refrozen meltwater (superimposed ice). This has helped lead to firn temperatures at 10m depth near the summit of Penny Ice Cap to warm by 10 °C between the mid-1990s and 2011, (Zdanowizc et al (2012). Geodetic methods indicate surface lowering of up to 1 m/year on all ice masses on Baffin Island and Bylot Island between 1963 and 2006 (Gardner et al.2012).

Cory Trepanier Great Glacier painting, which is of Coronation Glacier.

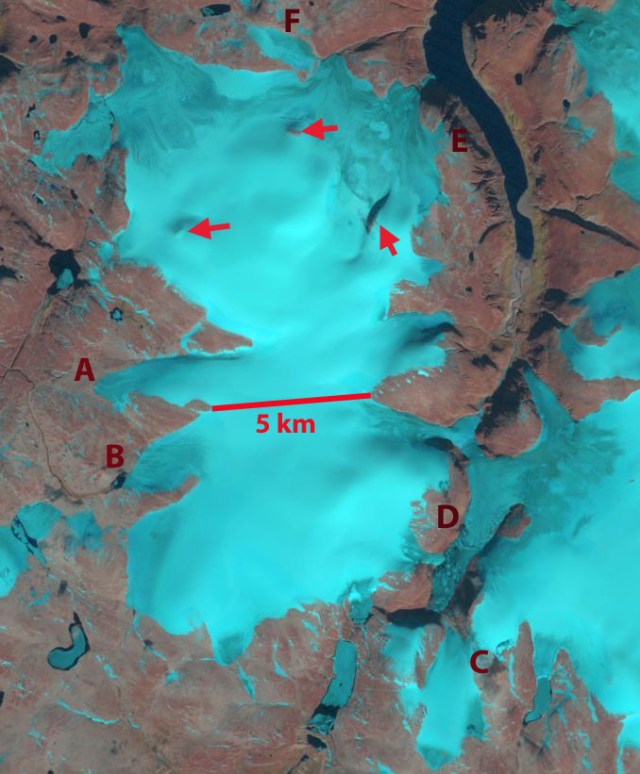

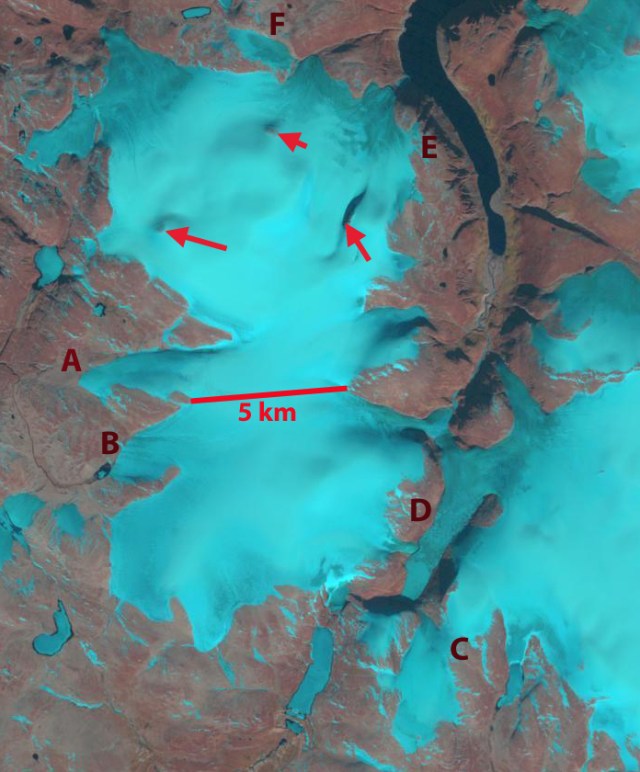

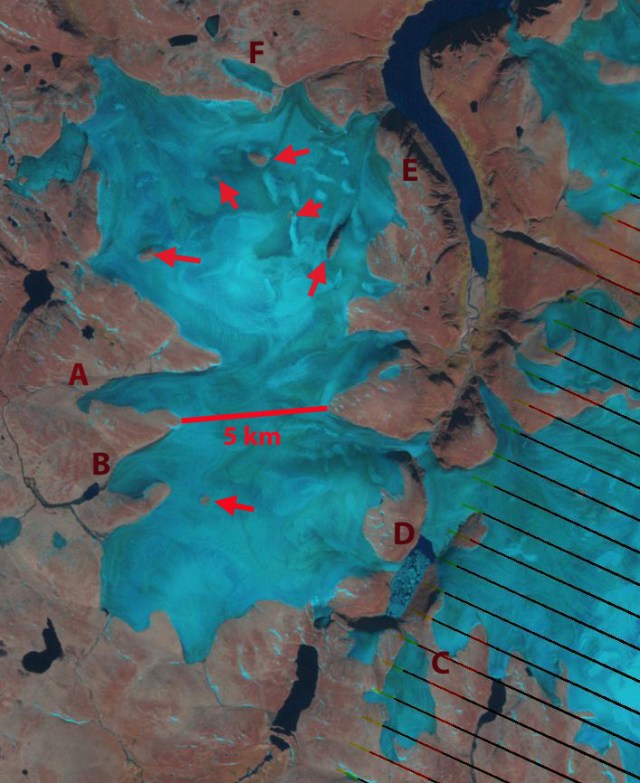

In 1989 Coronation Glacier terminates at the red arrow, where the main outlet stream has created a pair of small deltaic islands on the northern side of the fjord. By 1998 the terminus has retreated from both islands, with the northern one already having disappeared. There is a plume of glacier sediments in the fjord from the main river outlet emanating from below the glacier is near the center of the glacier. There has not been significant retreat on the south side of the glacier terminus. In 2002 both islands are gone, most of the retreat is still on the northern side of fjord. The plume of glacier sediments in the fjord from the main river outlet remains near the center of the glacier. In 2016 a new deltaic island has formed near the southern edge of the margin, indicating a shift in the position of the main river outlet emanating from below the glacier, this is also marked by a large plume. The island formed is larger than those observed in 1989 or 1998. The nature of the loosely consolidated glacier sediments deposited in a fjord is to subside/erode after the sediment source is eliminated. The retreat of the glacier insures that this will occur soon to the island here. The size of the island gives it potential to survive, based on satellite imagery. A visit to the island would be needed to shed light on its potential for enduring. Cory Trepanier is hoping to return for more paintings, which will illustrate better the change to us than a satellite image can. Retreat from 1989 to 2016 has been 1100 m on the northern side of the fjord and 500 m on the south side of the fjord. The average retreat of 800 m in 27 years is over 30 m/year, much faster than the 1880-1988 period. Locations 1-5 are tributaries that have each narrowed or retreated from the main stem of the glacier.

Closeup of the Coronation Glacier terminus and the new island in 2016, Sentinel 2 image.

The other noteworthy change is the lack of snowpack retained at locations 6-9 in the 2016 Sentinel image on small ice caps adjacent to Coronation Glacier in 2016. This continues a trend observed in 2004, 2009, 2010 and 2012 and that Zdanowizc et al (2012) also noted, 2009 image below. The high snowline is also evident on Grinnell Ice Cap The driving force has been an increase in temperature and this has caused mass losses on ice caps throughout the Canadian Arctic (Gardner, et al. 2011) and (Sharp et al, 2011).

Sequence of Landsat images indicating terminus positions. Red arrow is the 1989 terminus position and yellow arrow the 2016 terminus position.

2009 Landsat image of Coronation Glacier indicating lack of retained snowcover on surrounding ice caps.