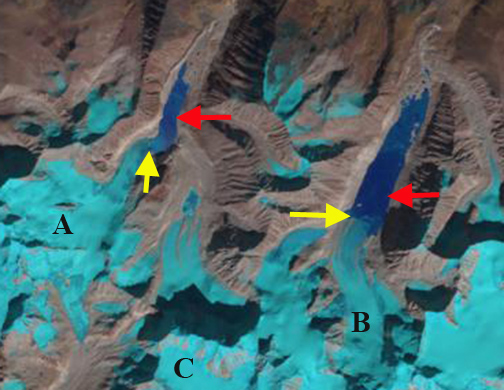

Lapche Glacier (Tibet 1), China in 1992 and 2018 Landsat images. The expansion of supraglacial ponds is evident between Point 2 and 3. A tributary that detaches between 1992 and 2018 is indicated by red arrow. The end of the clean ice and start of debris cover ice is just below Point 1 in 1992 and well above this Point in 2018.

Lapche Glacier (Tibet 1), China flows east from Lapche Kang (Lobuche Kang) in the Bum Chu River Basin. King et al (2017) examined the mass balance of 32 glaciers in the Everest region for the 2000-2015 period including the Lapche, which they called Tibet 1, and found a mass loss of ~0.5 m/year, with the loss of lake terminating glaciers at ~-0.7 m/year. King et al (2017) also observed that a number of these glaciers had nearly stagnant tongues with coalescing and expanding supraglacial ponds. Here we examine the expansion of the supraglacial ponds from 1992 to 2018 using Landsat images.

The lower four kilometers of Lapche Glacier in 1992 is relatively flat with the terminus at 5100 m and four kilometers upglacier at just 5200 m. In this stretch there are several small isolated supraglacial ponds between Point 2 and 3. At Point 1 is the end of the clean ice section of the glacier, with debris cover obscuring the underlying ice below this point. There is a tributary joining the glacier at the red arrow. In 2001 the snowline is at 5600 m, and there are a few more supraglacial ponds, but with a total surface area under 0.1 square kilometers. In 2015 the tributary at the red arrow has detached and the area covered by ponds has expanded and now cover ~0.5 square kilometers. The snowline in 2015 is at 5650-5750 m. In 2018 the supraglacial ponds have largely coalesced, and have an area of ~1.0 square kilometers. These lakes are on the verge of creating one larger lake as has happened on Rongbuk Glacier . The debris covered portion of the glacier now begins above Point 1, 1 km upglacier of its 1992 location. The snowline in 2018 is at 5650-5750 m.

King et al (2018) indicate a velocity of less than 10 m/year in the lower 5 km of the glacier, essentially stagnant. Point 1 is just over 6 km above the 1992 terminus. The retreat here is difficult to discern, but with the proglacial lake development it will soon be identifiable and in line with that of other glaciers in the area Duiya and Yanong. Zhang et al (2010) observed the loss of glacier area and lake expansion in the region from 1976-2006 driven by warming.

Lapche Glacier (Tibet 1), China in map view. Point 1-3 same as in images, ice flow indicated by blue arrows, elevation contours labelled at 51oo and 5200 m. Debris cover beginning noted at DC.

Lapche Glacier (Tibet 1), China in 2001 and 2015 Landsat images. The expansion of supraglacial ponds is evident between Point 2 and 3. A tributary that detaches between 2001 and 2015 is indicated by red arrow.