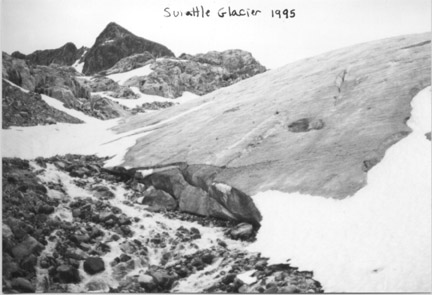

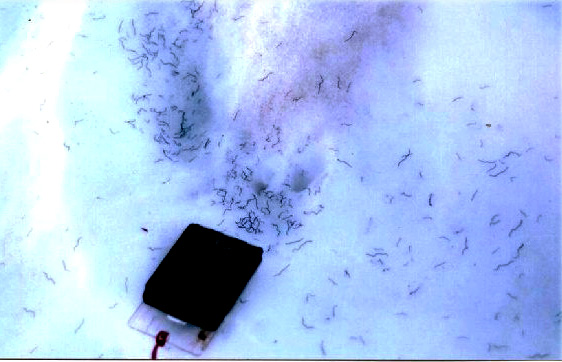

Here we provide a visual look inside a glacier in the North Cascades of Washington. Glaciers are not all the same, but the key internal ingredients in summer typically are in varied ratios: ice, meltwater, sediment and biologic material. In this case there are torrents of water pouring through the interior of the glacier, generated at the surface the day we are filming. We do measure the discharge and velocity of these streams. Once they drain englacially they are much slower as there are numerous plunge pools. There are also plenty of water filled crevasses. Some of the streams have considerable sediment in them, usually large clasts given the high velocity and low bed friction. In this case there are also a great many ice worms clinging to the walls of a water filled crevasse, and the walls of the stream channels. All of this water than merges by the terminus into an outlet stream. This again we measure. On the glacier we are measuring melt and at the end of the glacier runoff provides an independent measure of this melt as well. The water then heads downstream supplying many types of fish enroute to the ocean.

The last three years have led to considerable mass loss of glaciers in the area. This means less snowcover at the surface, which leaves less room for the ice worms to live and forces them into the meltwater regions. This also leads to more supraglacial stream channels, which develop and deepen. In many cases the streams deepen to the point that they become englacial. The increased ice area also should stress glacier ice worms as they live on algae, which resides largely in snow, which is less extensive and persistent in recent summers.