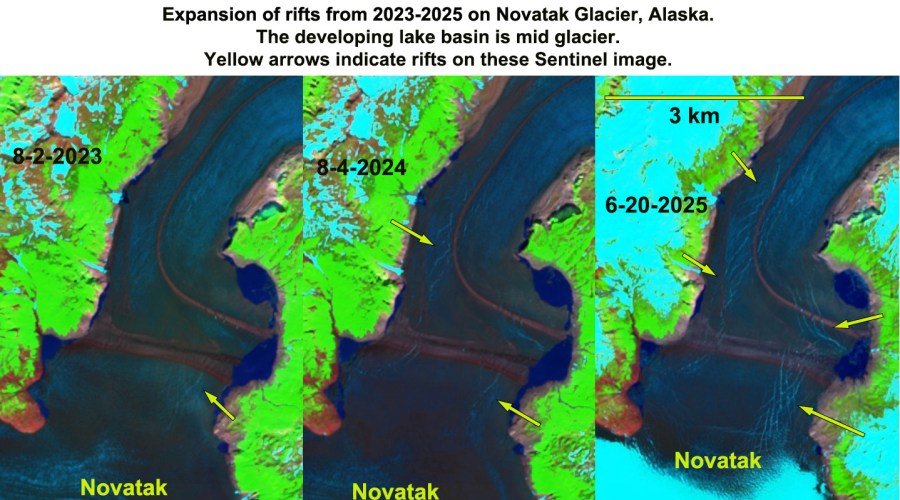

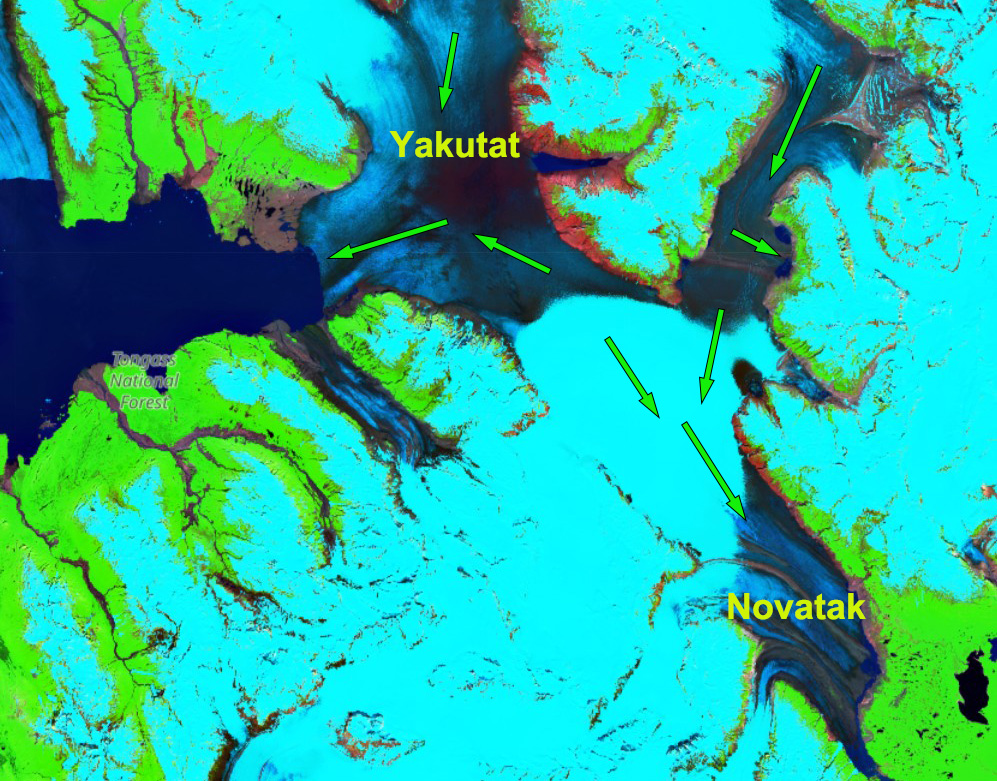

Ice flow in the region around the developing lake, which is near the boundary with Yakutat Glacier in Sentinel Image from June 20, 2025

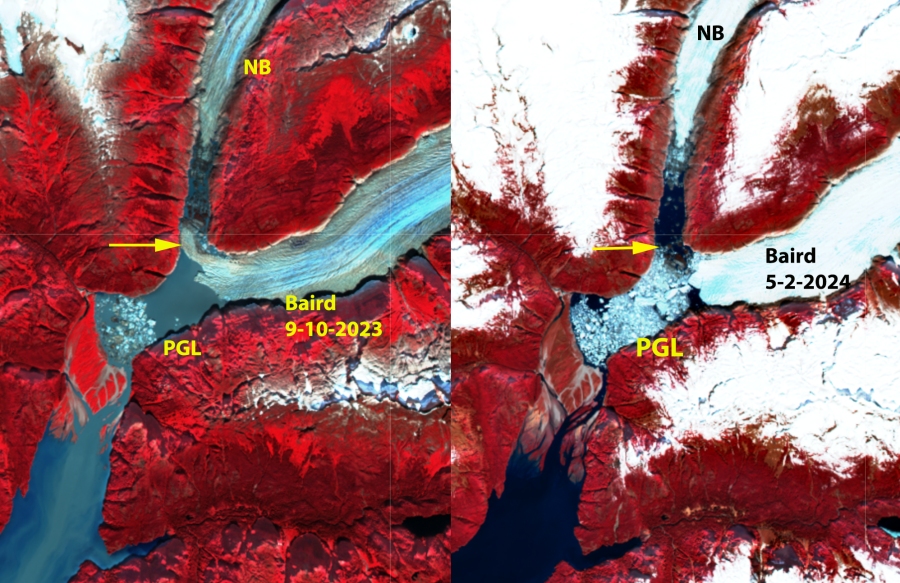

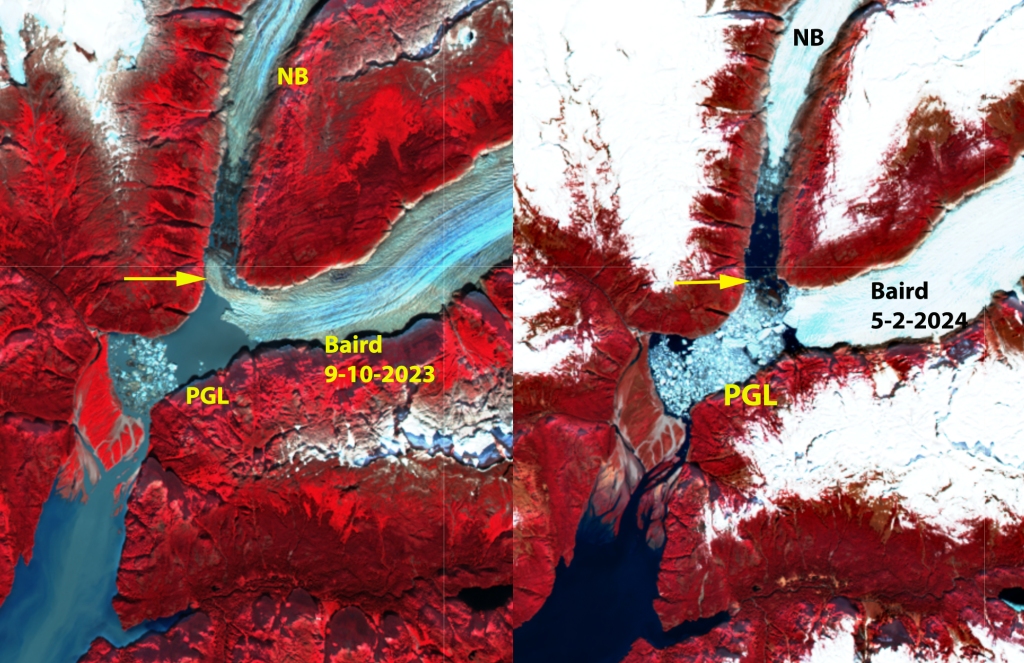

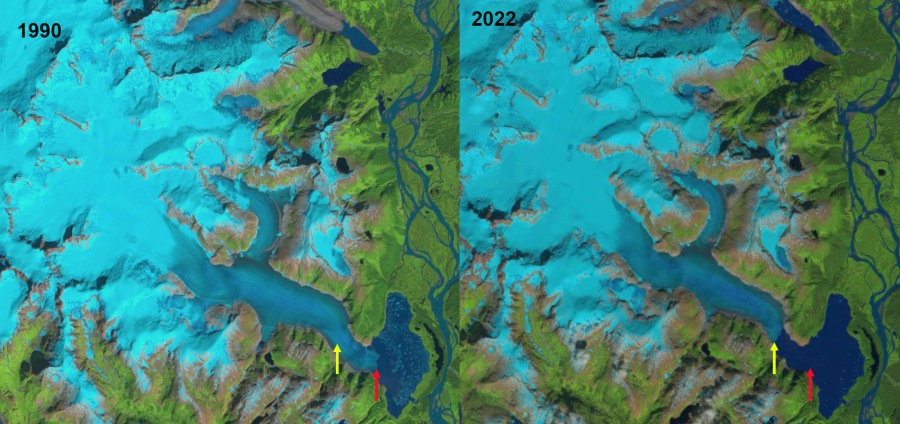

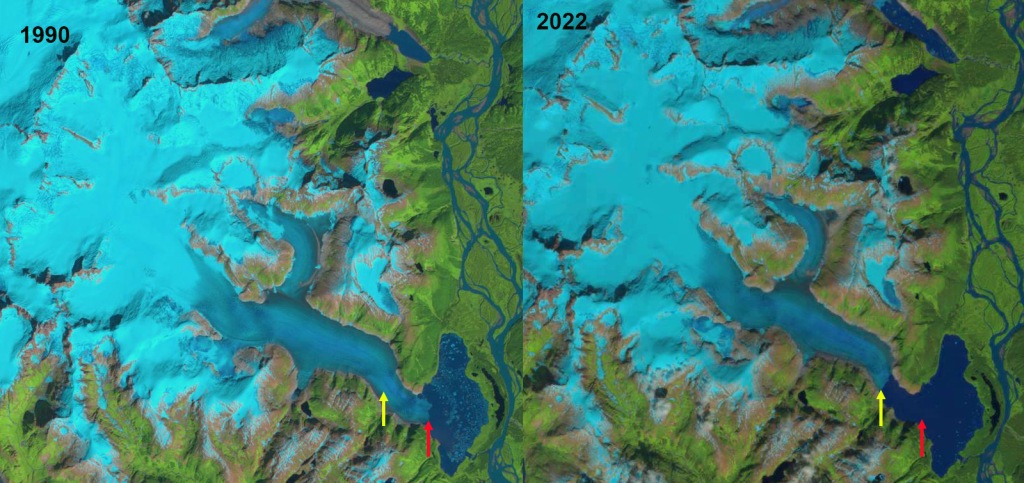

Novatak Glacier is between the Yakutat and East Novatak Glacier in southeast Alaska. The glacier retreated 1 km from 1987-2023 (NASA EO, 2015). The majority of the accumulation zone of these three glaciers is below 1000 m, which has made them particularly vulnerable to the warming climate. The result has been expansion of the proglacial lake, Harlequin Lake, at Yakutat Glacier from 1984 to 2024 from 50 km2 to 108 km2 (Pelto & NASA EO, 2024). There was no lake in 1908.

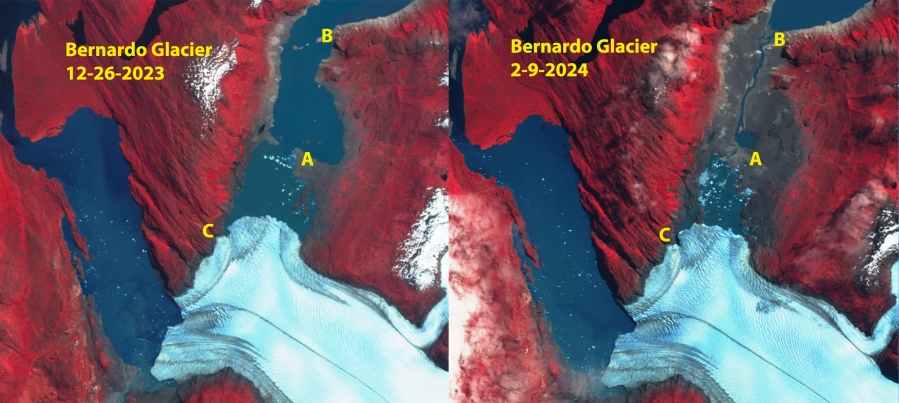

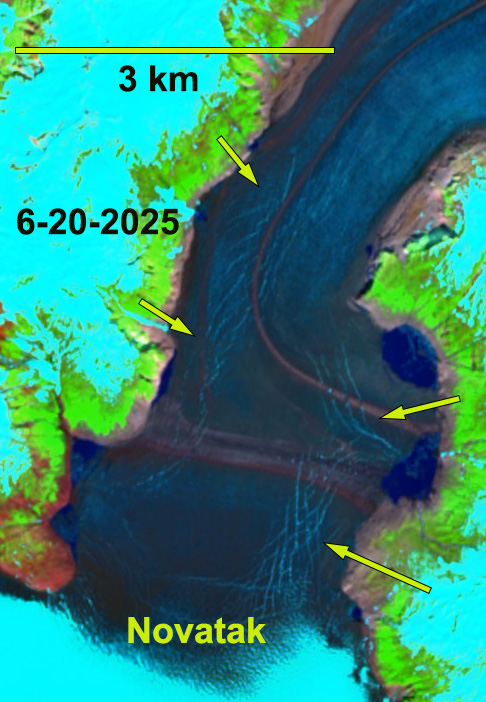

Novatak Glacier has been slow to form a substantial terminus lake unlike its neighbors, possibly because it lacks a sufficient basin. This has limited the retreat of this glacier as it thins. The developing rifts does show a large lake will form, with an area of 10-12 km2 . This will isolate the terminus from the main inflow to Novatak’s terminus, which will hasten a rapid meltdown. The rifts represent places where water level change causes flexure of the glacier, leading to their formation and expansion. They are not related to flow, but to uplift and down fall of ice where it is somewhat afloat. Rapid meltwater inflow to this basin will raise water level further stressing this region this summer. The degree of rifting indicates the ice is thin, but none are open enough to see water. This suggests breakup will not happen this summer. This type of rifting in 2010 and 2015 led to further breakups at Yakutat Glacier.

June 20, 2025 rifting of Novatak Glacier. The rifts represent places where water level change causes flexure of the glacier, leading to their formation and expansion. They are not related to flow, but to uplift and down fall.