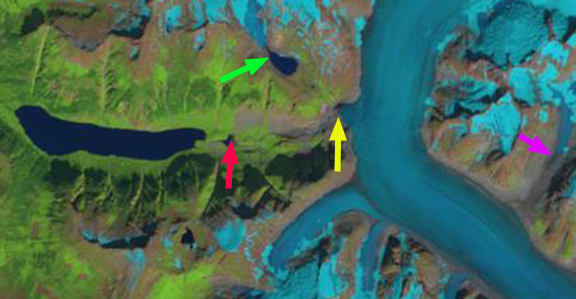

Field Glacier on Aug. 31, 2021 in a Sentinel image. Note former glacier junctions A and B where the glacier has separated this century. The 7.5 km2 lake did not exist when I first visited this glacier.

The Field Glacier flows from the northwest side of the Juneau Icefield, and is named for Alaskan glaciologist and American Geographical Society leader William O. Field. Bill along with his work around Glacier Bay helped initiate the Juneau Icefield Research Program, which Maynard Miller then ably managed for more than 50 years. The JIRP program is still thriving today led by Seth Campbell. In 1981, as a part of JIRP, I had my first experience on Field Glacier completing a snowpit in its upper accumulation area. In the summer of 1983 I met with Bill to discuss where to setup a long term glacier mass balance program. I ended up selecting the North Cascade Range. In 1984 we skied back to the same snowpit site on Field Glacier, finding 3.8-4.1 m of retained snowpack in crevasses. At the end of our 11th field season in the North Cascade Range I spent a couple of nights at Austin Post’s (USGS) house and he reviewed his choice for a glacier to name after Bill, who had passed earlier that month. This was truly a remote area, which was why it had remained unnamed.

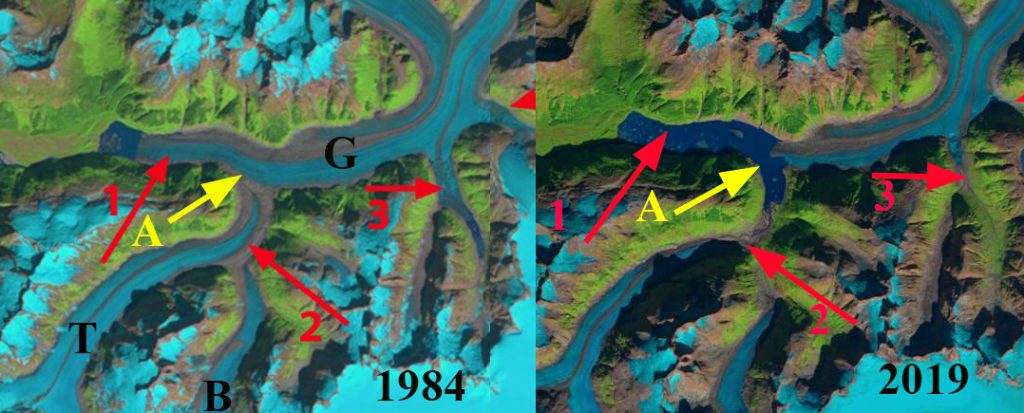

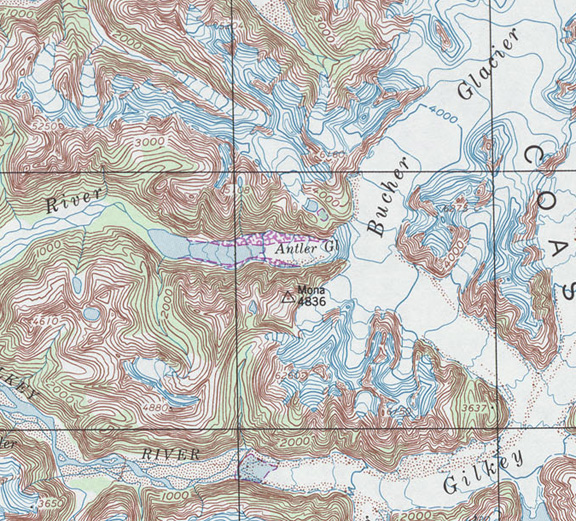

In 1984 the glacier began from the high ice region above 1800 meters, with two main branches joining at Point A and one significant tributary joining from the northern branch at Point B. There are icefalls near the snowline at 1350 meters on both the southern branch and the tributary entering at Point B. In 1984 the glacier descended the valley ending at 100 meters on the margin of an outwash plain. The meltwater feeds the Lace River which flows into Berners Bay. This post focusses on the changes from 1984-2021 using primarily Landsat imagery.

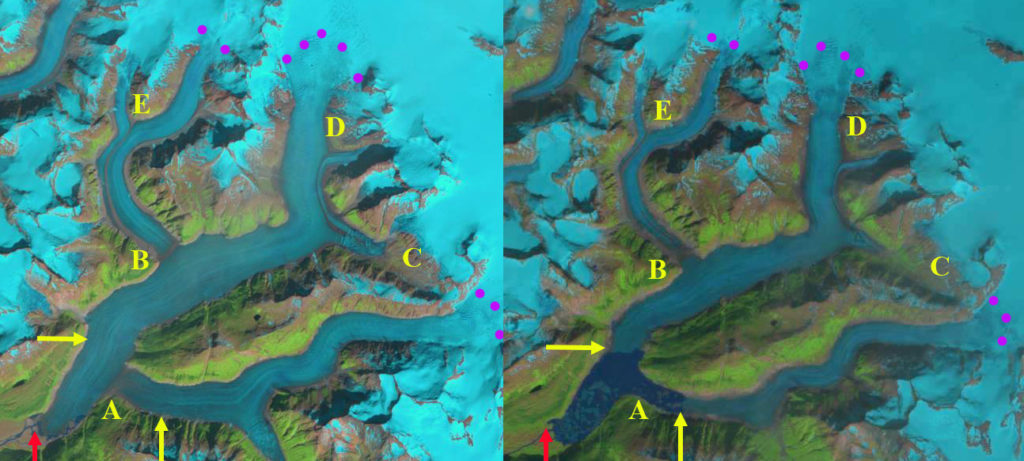

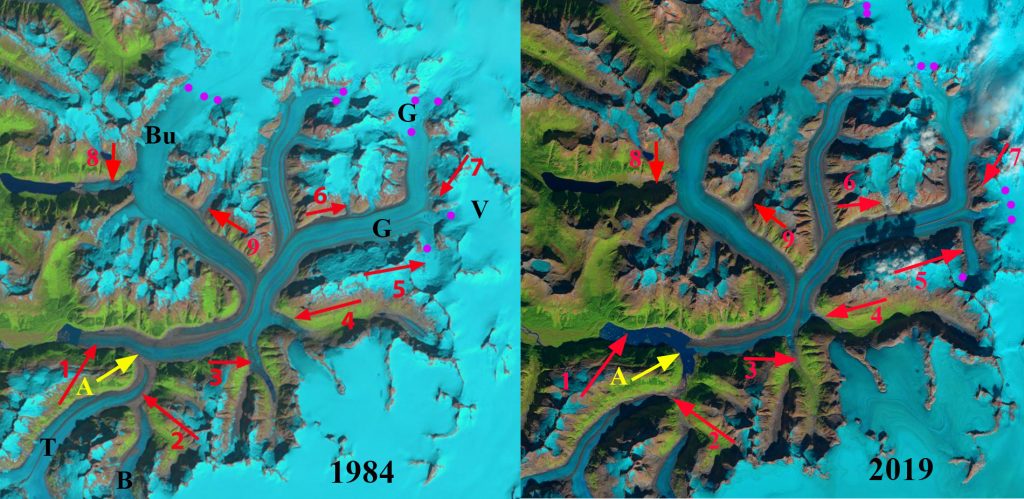

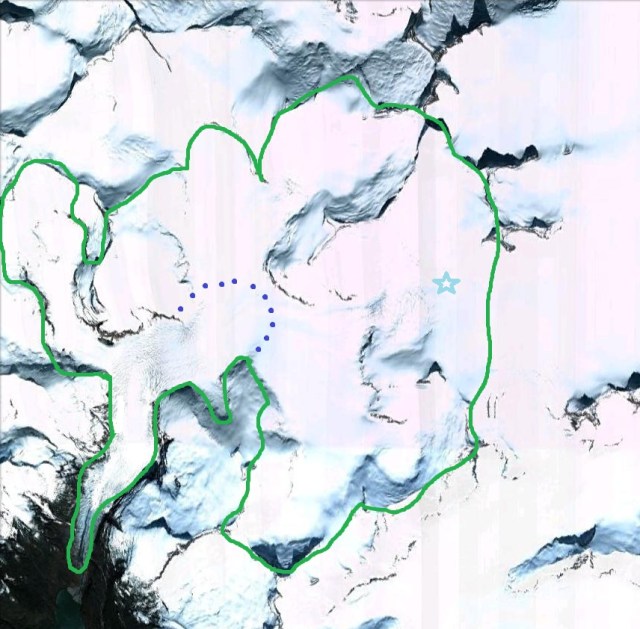

Field Glacier in Landsat images from 1984 and 2021 illustrating lake development, glacier separation at Point A and B and progressive detachment/separation at Point C,D and E. Purple dots indicate the snowline elevation at 1350-1400 m.

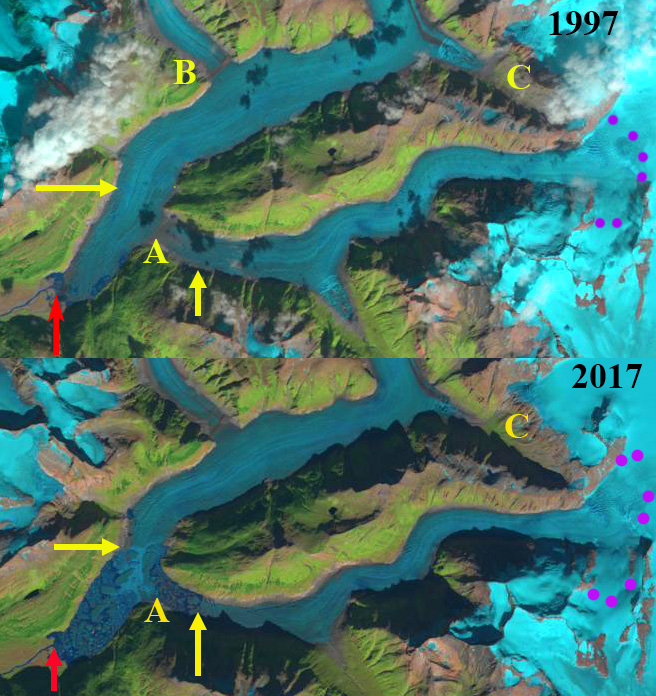

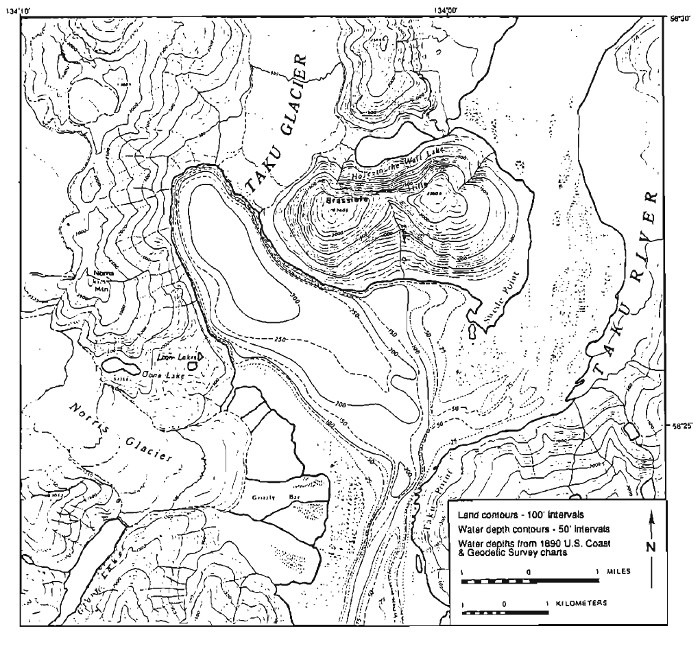

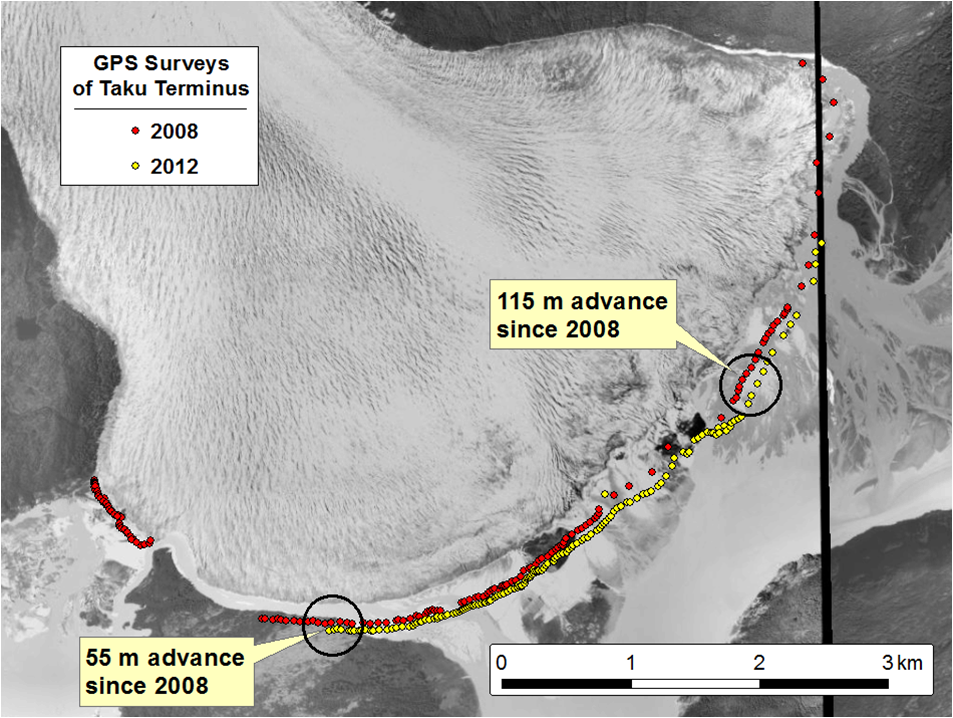

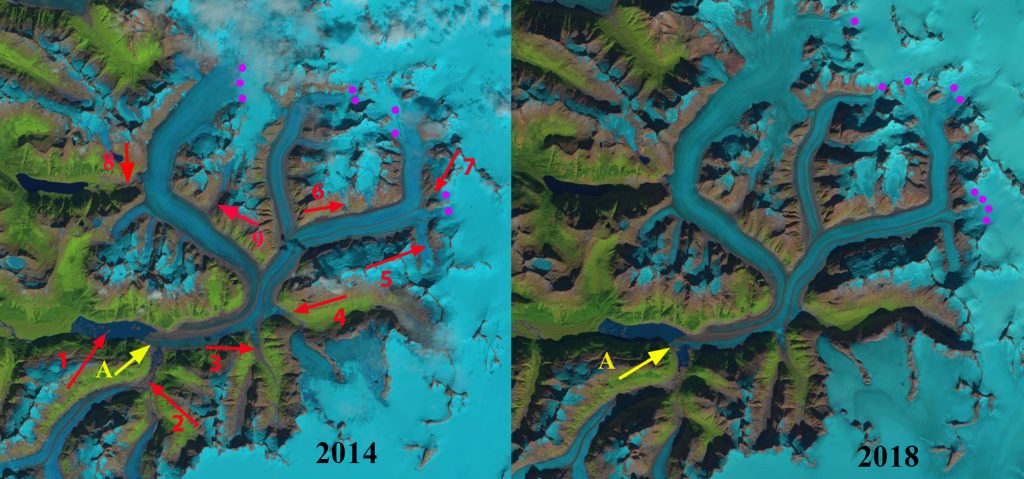

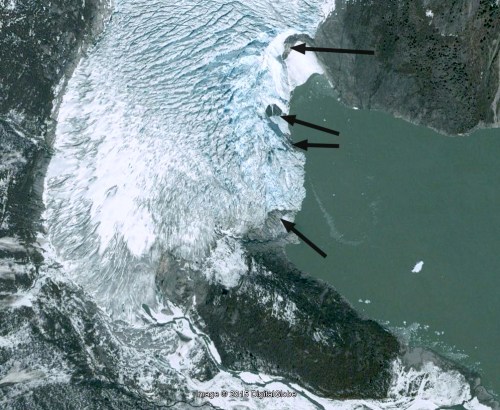

The USGS map from 1948 imagery and the 1984 imagery indicate little change in the terminus position. There is a narrow fringing proglacial lake along the southern edge of the terminus in 1984 with most of the margin resting on the outwash plain. In 1997 the proglacial lake was still a narrow fringing lake, though clearly poised to expand as it extended nearly the full perimeter of the terminus. By 2006 the proglacial lake at the terminus averaged 1.6 km in length, with the east side being longer. There were several small incipient lakes forming at the margin of the glacier above the main lake. In 2009 the lake had expanded to 2.0 km long and was beginning to incorporate the incipient lake on the west side of the main glacier tongue. There was also a lake on the north side of this tributary. This lake was noted as being poised to soon fill the valley of the south tributary and fully merge with the main lake at the terminus (Pelto, 2017). In 2013 Landsat imagery indicates the fragile nature of the terminus tongue that was about to further disintegrate, retreat from 1984-2013 was 2300 m and the lake had an area of 4.0 km2 (Pelto, 2017). This disintegration led to the separation of the two branches by 2017.

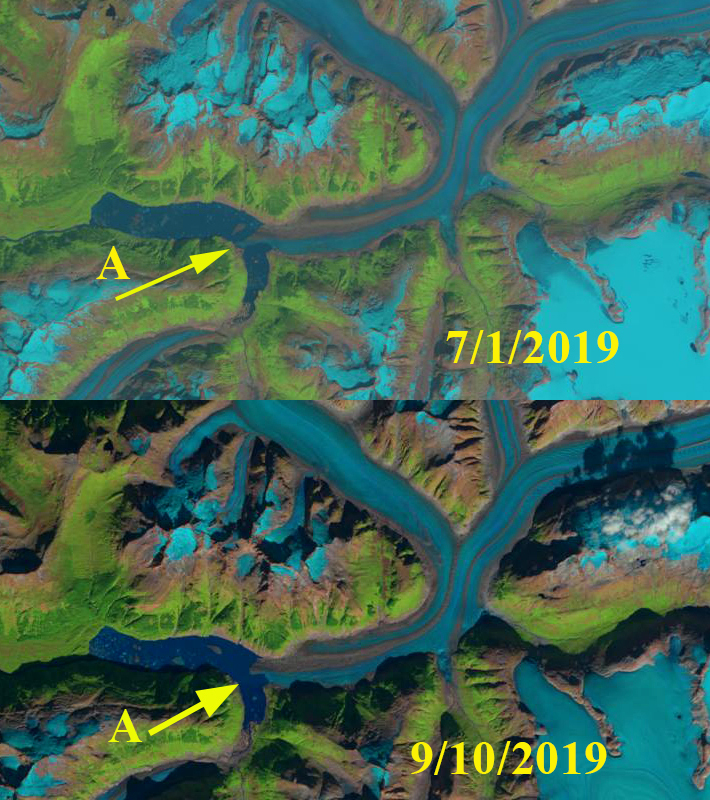

In 2021 the Field Glacier has two main branches are separated by 4 km, Point A. The tributary at Point B is also separated, no longer joining the main glacier. There is another separation imminent at the junction-Point E, 5 km of this former tributary. At Point C and D progressive detachment of smaller tributaries are evident. From 1984 to 2021, Field Glacier has experienced a retreat of 5500 m of the southern branch and 4100 m of the northern branch. The lake has expanded to 7.5 km2. Fringing lake on the northern branch indicates the lake will expand at least another 1 km. For the southern branch the glacier is close to what will be the lake margin. The record snowline elevation on the icefield in 2018 and 2019 (Pelto, 2019), has led to a continuation of the rapid mass balance loss, retreat, and lake development at Field Glacier. This glacier is experiencing retreat and lake expansion like several other glaciers on the Juneau Icefield, Gilkey Glacier, Llewellyn Glacier, and Tulsequah Glacier (Pelto, 2017).

Field Glacier in Landsat images from 1997 and 2017 illustrating lake development, glacier separation at Point A and B and progressive detachment/separation at Point C,D and E.

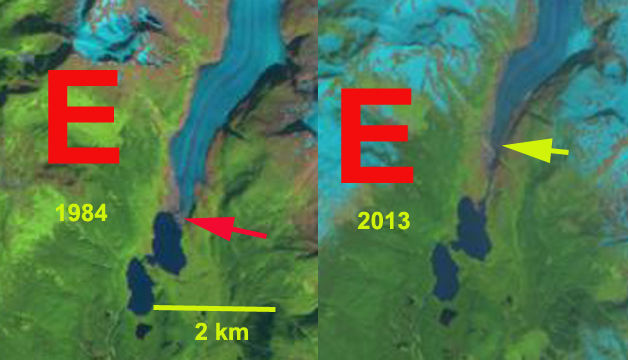

Field Glacier terminus in Landsat images from 1984 and 2013, dots indicate terminus, with pink arrows in 2013 indicating where marginal lakes have developed.

Field Glacier terminus in Landsat images from 2006 and 2009, red line is terminus with orange arrows indicating fringing lake development.