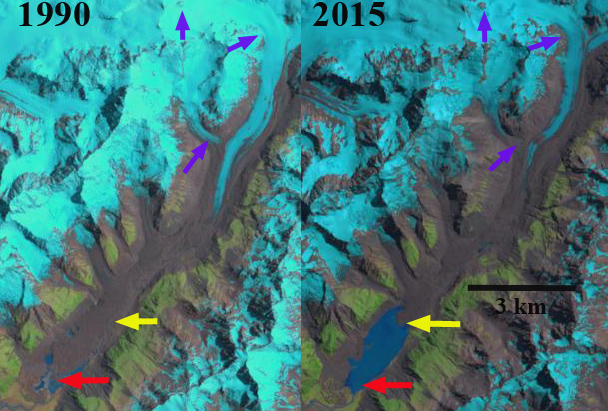

Mueller Glacier (M) in a Landsat image from 1990 and a Sentinel image from 2018. Red arrow is 1990 terminus, yellow arrow 2018 terminus, blue arrow glacier flow, and pink arrow in 2018 ablation valley cut into glacier.

Glaciers of the Southern Alps of New Zealand have been losing ice volume since 1978, with an increasing rate in the last decade (Pelto, 2017). The NIWA glacier monitoring program has noted that volume of ice in New Zealand’s Southern Alps has decreased 5.8 cubic kilometres, more than 10% in the past 30 years. More than 90% of this loss is from 12 of the largest glaciers in response to rising temperatures over the 20th century. Three of these glaciers are the Tasman, Mueller and Hooker Glacier. If we look back to the 1972 Mount Cook Map, see below, no lakes are evident at the terminus of Hooker (H), Mueller (M) or Tasman Glacier (T), pink dots indicate terminus location, top image. Now it is a developing lake district.

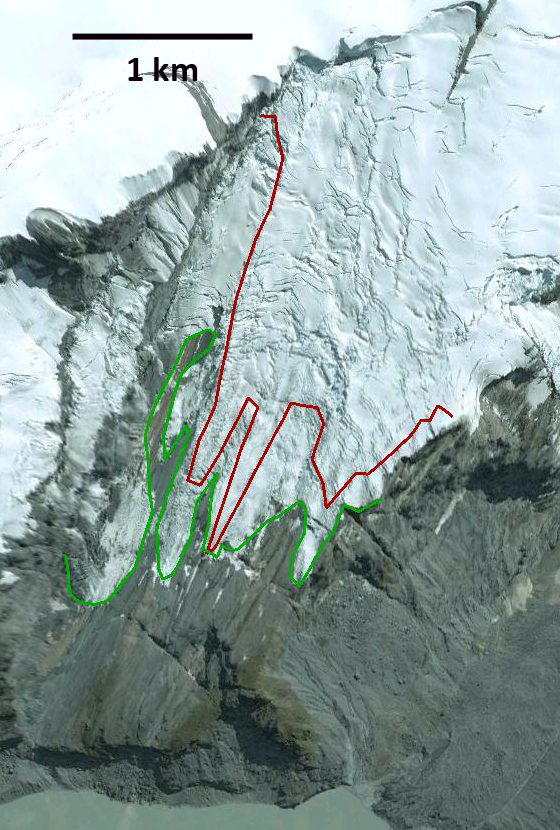

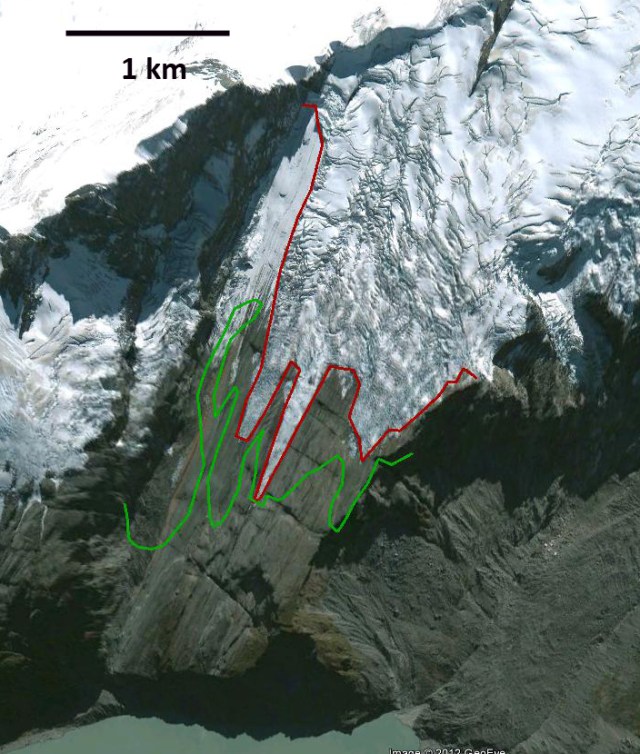

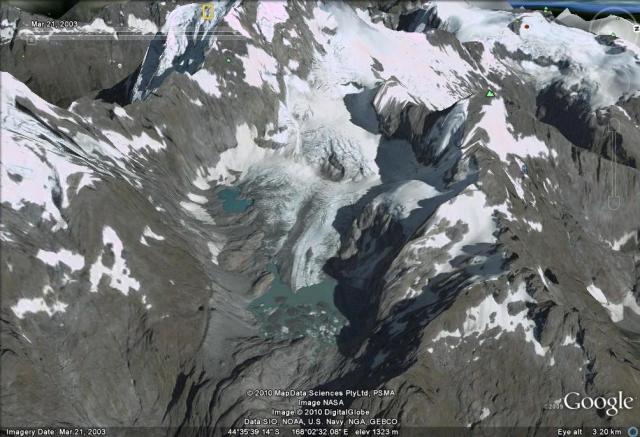

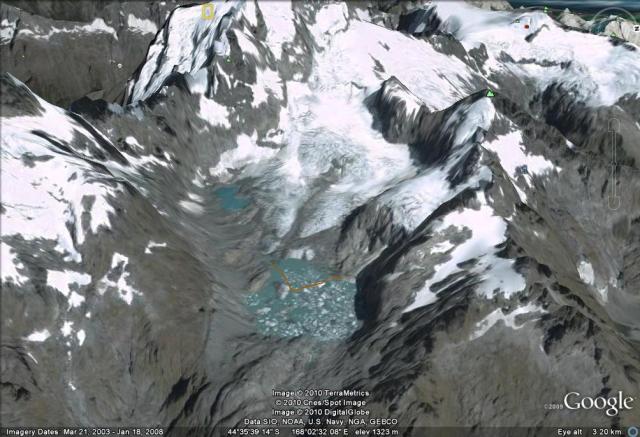

Mueller Glacier drains the eastern side of Mount Sefton, Mount Thompson and Mount Isabel. The lower section of the glacier is debris covered in the 2.5 km long valley reach from the terminus at 950 m to 1250 m. A comparison of the Mueller Glacier in a sequence of Landsat images indicates a fringing discontinuous area of water along the southern glacier margin in 1990. In 2000 the lake at the end of Hooker Glacier had developed and was 400 meters long. By 2004 the Mueller Glacier Lake had expanded to a length of 700 meters. By 2011 the lake had reached 1400 meters in length. By 2015 the lake had reached 1800 meters in length. Mueller Lake had a surface area of 0.87 km2 and a maximum depth of 83 m (Robertson et al, 2012). From 2015-2018 the terminus has collapsed into the lake with icebergs and other attached ice remnants. The retreat has left a lake that is 2700 m long, a retreat of 2300 m since 2000. The lake basin is 1.6 km2 with 15% filled with remnant ice. Above the current terminus in not a typical convex valley glacier, but a concave reach of debris covered ice with significant melt valleys and hollows indicating stagnation in the lowest 1.6 km. Pictures of the terminus from 2018 taken by Jill Pelto, UMaine indicate the high turbidity of the lake, which is expected from a debris covered ablation zone. The lack of relief of the relict ice is also evident.

Mueller Glaier drains into Lake Pukaki,a along with Murchison,Hooker and Tasman Glacier, where water level has been raised 9 m for hydropower purposes. Water from Lake Pukaki is sent through a canal into the Lake Ohau watershed and then through six hydropower plants of the Waitaki hydro scheme: Ohau A, B and C. Benmore, Aviemore and Waitaki with a combined output of 1340 MW. Meridian owns and operates all six hydro stations located from Lake Pūkaki to Waitaki. Reductions in glacier area in the watershed will lead to reduced summer runoff into the Lake Pukaki system.

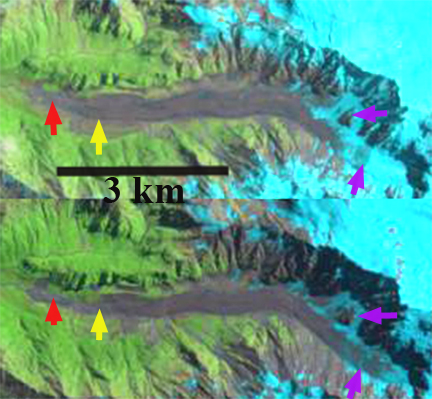

The glacier has been fed by three different glaciers flowing off of Mount Sefton. Two of them Tuckett and Huddlesoton (pink arrow) are no longer delivering significant ice to the Mueller, only modest avalanching now spills onto the Mueller Glacier. Only the Frind Glacier (yellow arrow) is contributing to the Mueller Glacier. This is similar to the situation on nearby Murchison Glacier. Further the lack of ice connection from Huddleston and Tuckett Glaciers to Mueller is again evident, pink arrow. The lake will continue to expand through minor calving and downwasting.

Field work images from Jill Pelto looking across Mueller Lake towards Hooker Lake and Mt. Cook. Some remnant ice is visible.

View southwest toward the head of Mueller Lake and terminus of Mueller Glacier notice stream dissecting stagnant ice at head of lake. Picture is from Noel Potter, UMaine, 2/2018

Mueller Glacier (M) in a Landsat image from 2000 and 2015. Red arrow is 1990 terminus, and yellow arrow 2018 terminus.

1972 Map of region when Tasman, Mueller and Hooker Glacier lacked proglacial lakes and Landsat image in 2011 after lake development.