Map of the Waitaki Hydropower system, from Meridian and images of the system taken by Jill Pelto January 2017.

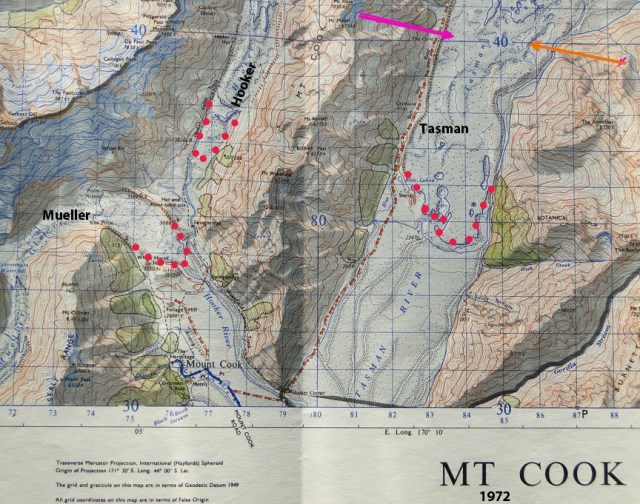

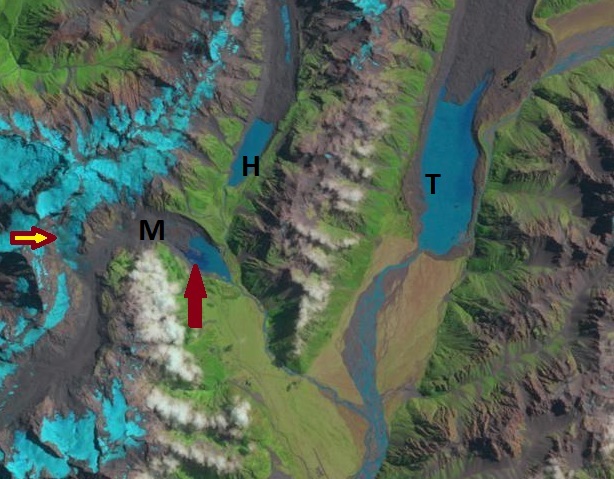

Hooker Glacier, Mueller, Murchison and Tasman Glacier drain into Lake Pukaki, where water level has been raised 9 m for hydropower purposes. Classen Glacier, Grey Glacier and Godley Glacier drain into Lake Tekapo. Lake Tekapo and Lake Pukaki are both utilized for hydropower. Water from Lake Tekapo is sent through a canal to Lake Pukaki. Water from Lake Pukaki is sent through a canal into the Lake Ohau watershed and then through six hydropower plants of the Waitaki hydro scheme: Ohau A, B and C. Benmore, Aviemore and Waitaki with a combined output of 1340 MW. Meridian owns and operates all six hydro stations located from Lake Pūkaki to Waitaki. Below the Benore Dam is pictured,. Interestingly salmon have been introduced into the Waitaki River system for fishing near its mouth. Benmore Lake itself is an internationally renowned trout fishing spot, providing habitat for both brown trout and rainbow trout. The reduction of glacier area in the region due to retreat will reduce summer runoff into Lake Pukaki and this hydropower system, which will reduce summer flow in the Waitaki River.

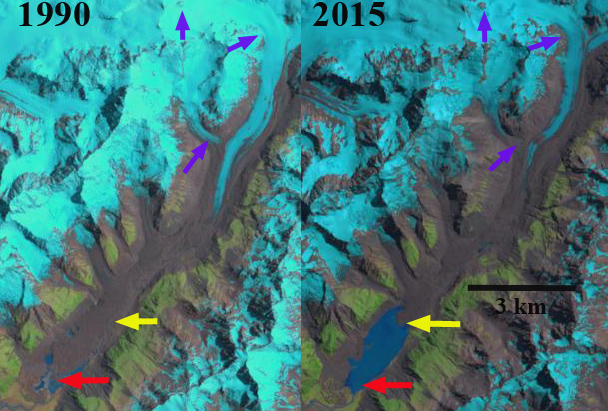

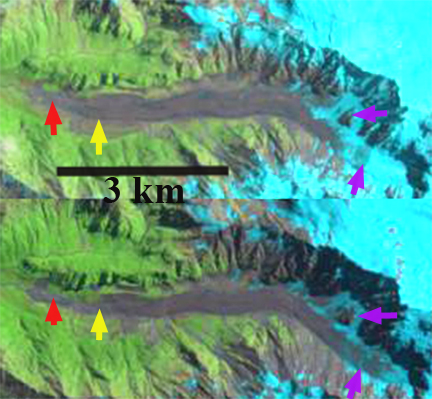

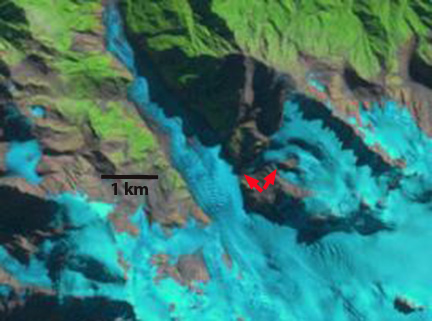

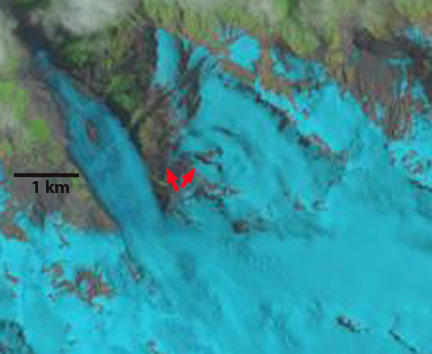

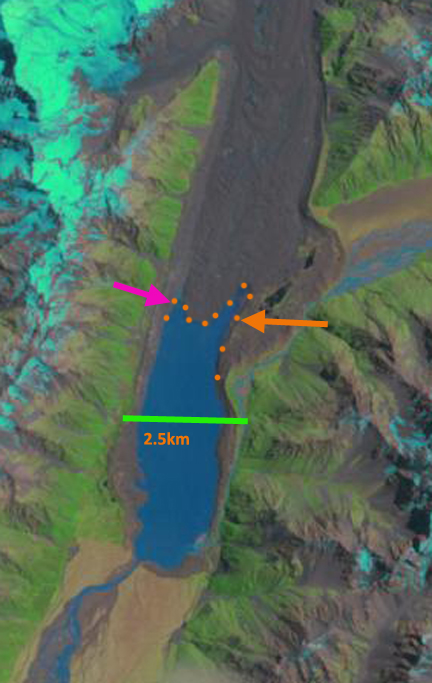

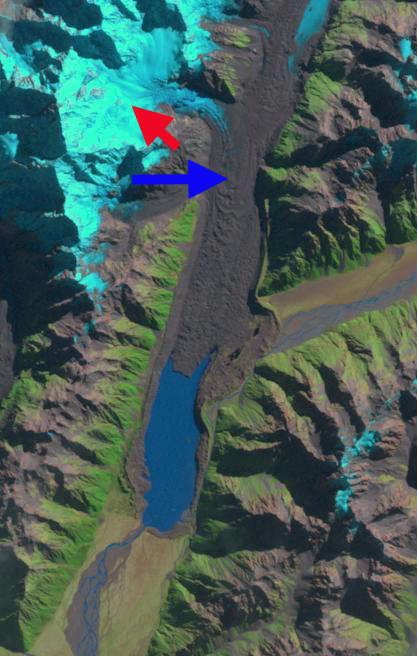

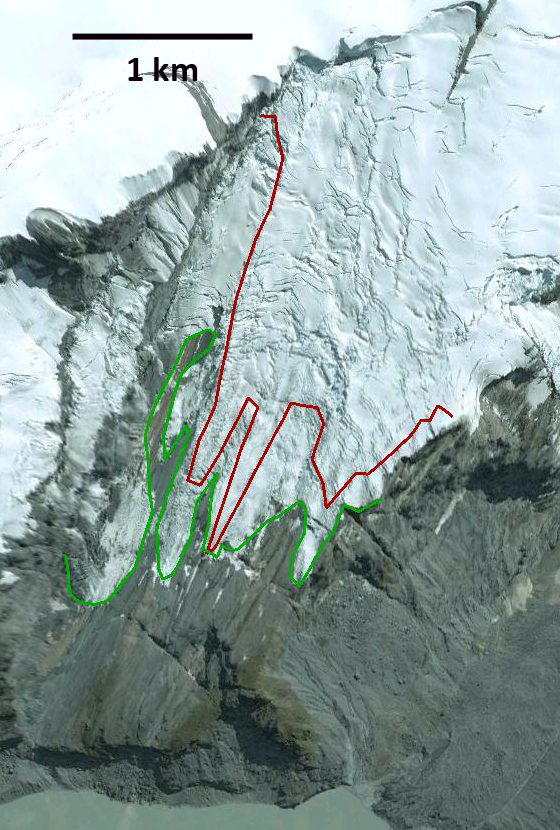

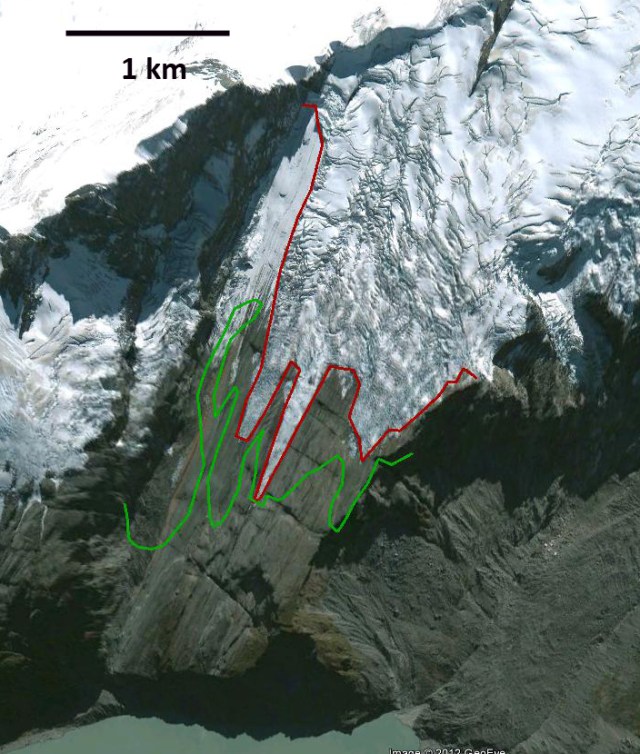

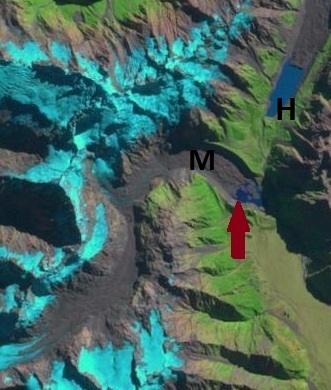

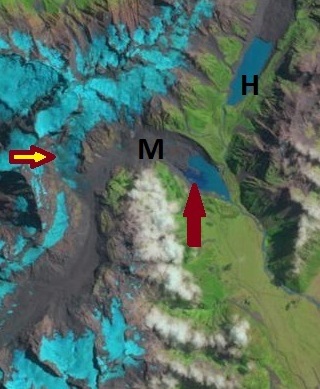

Mueller Glacier has had a 1500 m retreat from 1990-2015, which will continue in the future as the lower 2 km section of the glacier is stagnant. Hooker Glacier retreated 1200 m from 1990 to 2015 and the lake expanded to 2300 m, with the retreat enhanced by calving. Tasman Glacier retreated 4.5 km from 1990 to 2015 primarily through calving into the expanding proglacial lake. Murchison Glacier has retreated 2700 m From 1990 to 2015. The rapid retreat will continue as 2010, 2013 and 2015 imagery indicate other proglacial lakes have now developed 3.5 km above the actual terminus. Classen Glacier has retreated 1000 m from 1990 to 2015 leading to expansion of the lake it ends in (Pelto, 2016). Godley Glacier has retreated 1300 m from 1990-2015 with an equal amount of lake expansion (Pelto, 2016). The expansion of debris cover is striking from 1990 to 2015 this indicates reduced flow from the accumulation zone. Grey Glacier has a heavily debris covered terminus that prevents accurate assessment of retreat. Overall these 7 glaciers make up the majority of the volume and area loss of New Zealand glaciers, which has been dominated by 12 large glaciers (Salinger and Willsman, 2008). The changes of 12 different glaciers have been examined in detail and are compile at the New Zealand Glacier Index. The loss of summer glacier runoff from each square kilometer of lower elevation glacier area that has disappeared is at least 50,000 cubic meters per day (Pelto, 2016). Given the 12 square kilometer loss in the terminus zone of just these seven glaciers, you have a 600,000 cubic meter per day loss in runoff that would be heading into the Pukaki-Takapo-Waitaki Hydro system. The retreat is driven by mass losses as indicated by the rising snowline observed by NIWA.

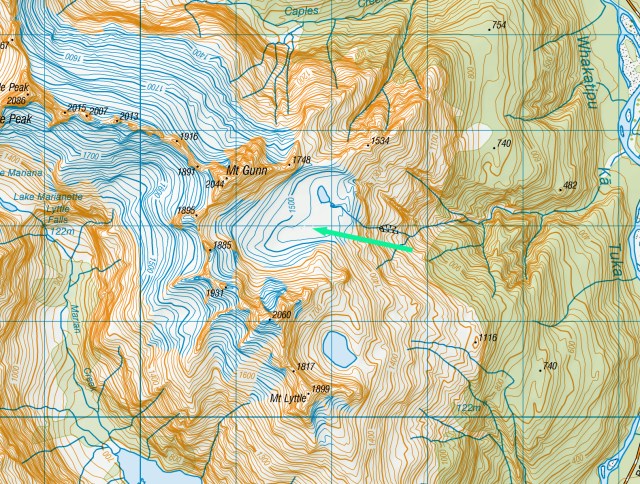

Map of the glaciers feeding Lake Pukaki and Lake Tekapo. M=Mueller, H=Hooker, T=Tasman, Mu=Murchison, Gr=Grey, Go=Godley and C=Classen. From Pelto (2016)

Canals connecting Lake Pukaki and Lake Tekapo