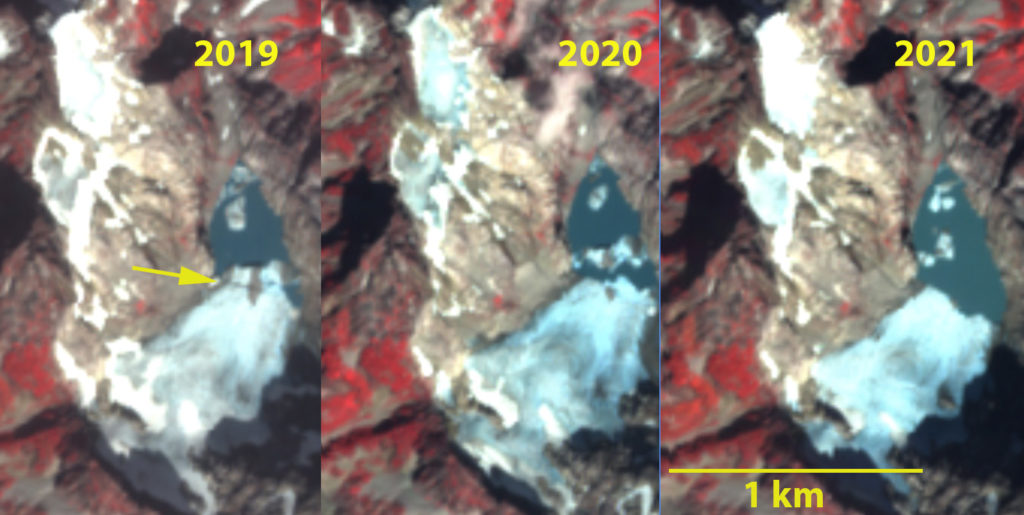

Colonial Glacier in late summer false color Sentinel 2 images from 2019, 2020 and 2021. Yellow arrow indicates step that calves in 2020. Notice the ~10% of snowcover (bright white) remaining on glacier surface with more melt to come.

An alpine glacier disappears when it no longer has a persistent accumulation zone (Pelto, 2010). When this occurs the glacier is typically limited in size, but still can have significant ice thickness that takes time to melt away. Here we look at three glaciers I have worked on, where two disappeared and the third is disappearing in the North Cascade Range, Washington.

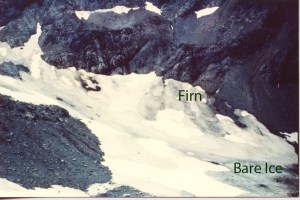

Lewis Glacier was a small cirque glacier in the drier part of the range, near Rainy Pass. In 1985 during my second visit to the Lewis Glacier, was the first time I confronted the idea of a glacier disappearing. We were able to peer down several crevasses and see the bottom of the Lewis Glacier, measurements indicated a maximum depth of 12 meters over an area the size of a football field/soccer pitch. This glacier had been selected for the North Cascade Glacier Climate Projects’s mass balance program assessing mass balance on 10 glaciers across the mountain range. This size made it attractive to observe in terms of response to climate change. The USGS map indicated a significant glacier with an area of 0.12 km2 in the 1950’s. By 1985 (top image) the glacier had lost half of its mapped area, there were still some significant blue ice areas, and areas of firn, snow several years old that is not yet glacier ice. Return visits each summer over the next few years chronicled the demise of the glacier. By 1988 (middle image) the glacier had shrunk dramatically even since 1985, the thickest ice measured was 5-6 meters. By 1990 the glacier was gone (bottom image), no blue ice left in the basin, the blue arrows indicate the lateral moraine above the now empty glacier basin. At the time I had not developed the model for forecasting glacier survival (Pelto, 2010). At bottom is 2021 image of the cirque basin with no glacier.

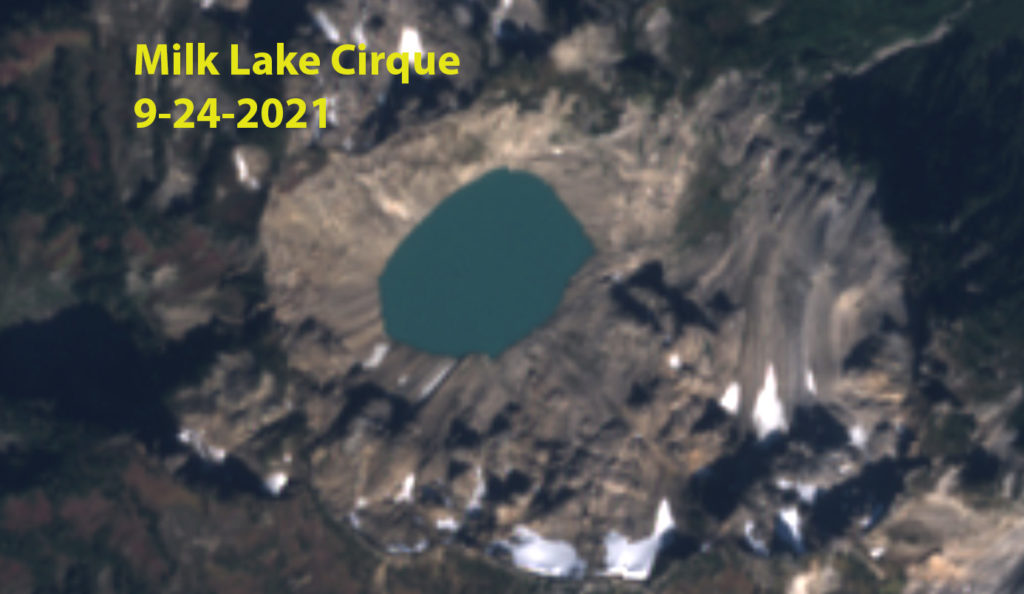

Milk Lake Glacier was a small glacier on the north flank of Glacier Peak in the North Cascades, Washington. The flat topography over the lake indicated a very thin unstable glacier area. In the USGS map for Glacier Peak in the based on 1979 aerial photographs, Milk Lake Glacier fills most of the Milk Lake Basin, had an area of 0.24 km2 with just a fringe of lake visible. Thw flat topography indicates the thin unstable nature of this part of the glacier. By 1988, Milk Lake had formed, a notably circular new alpine lake, the former glacier ice still filled part of the lake as ice bergs. The glacier had retreated to the margins of the lake fringing the west side of the lake. The fringing ice was clearly thin, we found several crevasses that reached bedrock 5-10 m down. In 1994 on a return visit in miserable weather (camera got too wet to function), there was no longer any icebergs in the lake and the lake was more of a jade to turquoise color. The fringing ice had lost about half of its area since 1988. This glacier remnant was not going to last long. By the end of 2005 the glacier had disappeared. The lake retains a beautiful jade color that will slowly become more azure as glacier flour settles. In 2021, see image bottom, the basin does not look like a recently glaciated basin.

Colonial Glacier is a cirque glacier in the Skagit River Watershed, North Cascades of Washington. The North Cascade Glacier Climate Project has made six visits to this glacier since 1985. Meltwater from this glacier enters Diablo Lake above Diablo Dam and then flows through Gorge Lake and Gorge Dam. These two Seattle City Light hydropower projects yield 360 MW of power. In 1979 the glacier was clearly thinning, having a concave shape in the lower cirque, but still filled its cirque, there is no evidence of a lake in this image from Austin Post (USGS). In 1985 my first visit to the glacier there was no lake at the terminus. We measured the glacier area at 0.92 km2. In 1991 the lake had begun to form, second image, but was less than 30 m across. The upper glacier was a smooth expanse of snow. By 1996 the lake was evident, and was 75 meters across. In 2001 the lake had expanded to a length of 125 meters. By 2006 the lake was 215 m in length, and had some thin icebergs broken off from the glacier front. From 2019-2021 a series of late summer Sentinel 2 images indicate the lack of retained snowcover necessary for survival. In 2019 15% of the glacier is snowcovered with three weeks left in the melt season. The terminus is just below a step in the glacier surface. In 2020 there is only 10% snowcover with two weeks left in the melt season. The portion of the glacier below the step has calved off and is now an iceberg in the lake. In 2021 the exceptional June heat wave took its toll and by the end of August the glacier only has 10% retained snowcover. The glacier area in 2021 is 0.26 km2, a 70% decline in area. The glacier has retreated 440 m and now is 520 m long. The lake has an area of 0.1 km2. The continued losses of Colonial Glacier are not being replenished by snowfall, this business model can only lead to the glacier disappearing. Colonial Glacier still has substantial area and thickness that will allow it to survive for a couple more decades. The continued loss of glacier area from Colonial and all other glaciers in the region reduce the mitigating affect of enhanced summer streamflow due to higher glacier runoff during warm dry periods.

Lewis Glacier cirque in Sentinel 2 image from 2021, Lewis Lake is lower right.

Milk Lake cirque in 2021, looking like a basin that was not recently glaciated.