Landsat images of Tulsequah Glacier on June 22 and July 5, 2021. Lake No Lake is between the yellow arrows with the margin of glacier extending upvally on June 22nd. By July it has receded back to main valley and lake has largely drained. The former location of Tulsequah glacier dammed lake is at red arrow.

Tulsequah Glacier, British Columbia drains east from the Juneau Icefield and is best known for its Jökulhlaups or glacier lake outburst floods (GLOF) from Tulsequah Lake and Lake No Lake dammed by Tulsequah Glacier in northwestern British Columbia, Canada (Neal, 2007). The floods pose a hazard to the Tulsequah Chief mining further downstream. This glacier feeds the Taku River which has seen a significant decline in salmon in the last decade (Juneau Empire, 2017).The continued retreat of the main glacier at a faster rate than its subsidiary glaciers raises the potential for an additional glacier dammed lakes to form. The main terminus has disintegrated in a proglacial lake. Pelto (2017) noted that by 2017 the terminus has retreated 2900 m since 1984, with a new 3 km long proglacial occupying the former glacier terminus. The USGS has a stream gage measuring a range of parameters including turbidity and discharge which can identify a GLOF. Neal (2007) examined the 1988-2004 period identifying 41 outburst floods from 1987-2004. Here we examine Landsat images and USGS records of Taku River to quantify the 2021 GLOF event between June 25 and July 3.

USGS records of turbidity and discharge on Taku River that indicate the onset on glacial lake drainage and of the GLOF event on July 3, note purple arrows.

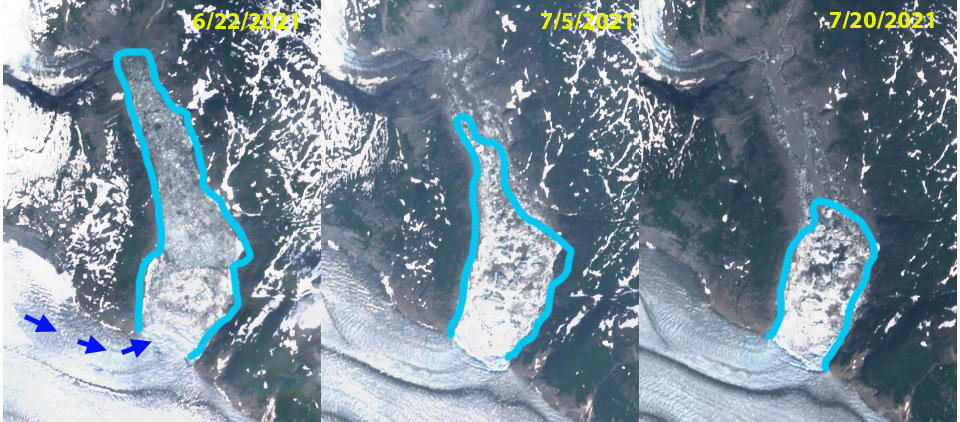

On June 22, 2021 the region between the yellow arrows is an iceberg choked lake. The red arrow indicates the location where Tulsequah Lake used to expand, it is limited. The terminus of the glacier reaching upvalley 600 m from the main glacier. Discharge is at 60,000 cfs and the turbidity is at ~100 FNU. Starting on the June 25th through the 27th turbidity rises to 400 FNU, while discharge rises to 90,000 cfs. This is during a protracted dry period and is the result of the beginning of increased glacier discharge from the lake. On July 27th-June 30th it is evident that the margin of the distributary glacier tongue has receded ~500 m back to the main glacier margin, representing a terminus collapse generating icebergs likely resulting from a fall in water level. There is no change in the small Tulsequah Lake at the red arrow. On July 3rd turbidity rises above 500 FNU and discharge exceeds 130,000 cfs, this is at the high end of the typical peak GLOF events from Lake No Lake as noted by Neal (2007) from 90,000-130,000 cfs. This is the main event and was reported by the USGS. By July 5 Landsat imagery indicates the water level has dropped between the yellow arrows, resulting in more prominent icebergs. The Sentinel image illustrates the zone of iceberg stranding as well. The icebergs continue to melt away by July 20. No change at the red arrow. If we look back to Sept. 2020 we see what Lake No Lake will appear like by the end of summer and that the distributary terminus margin does not extend upvalley at that time. The large proglacial lake that has formed after 1984 due to retreat helps spread out the discharge from ice dammed lake GLOF’s of Tulsequah Glacier. This lake will continue to expand and the damming ability of the glacier will continue to decline, which will eventually lead to less of a GLOF threat from Lake No Lake.

Sentinel images from June 22, July 5 and July 20 of the area of the lake and then the area of stranded icebergs. Note how almost the entire width of a the northern tributary flows into this valley.

Landsat images of Tulsequah Glacier on June 27 and June 30. Lake No Lake is between the yellow arrows. The former location of Tulsequah glacier dammed lake is at red arrow.

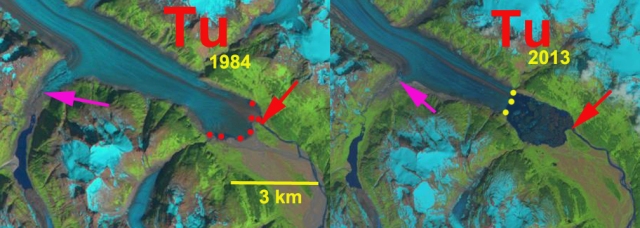

Tulsequah Glacier in 1984 and 2017 Landsat images. The 1984 terminus location is noted with red arrows for the main and northern distributary tongue, southern distributary red arrow indicates lake margin. The yellow arrows indicate the 2017 glacier terminus locations. The retreat of 2900 m since 1984 led to a lake of the same size forming. Purple dots indicate the snowline.

Landsat images of Tulsequah Glacier on Sept. 15, 2020. Lake No Lake now drained fills between the yellow arrows. The former location of Tulsequah glacier dammed lake is at red arrow.